In September 2007 I attended a book reading by Zara Houshmand in Oakland, where she read passages of A Mirror Garden, the Monir Shahroudy Farmanfarmaian memoirs she had co-authored. I remember as I asked her to sign my book for me, I asked her “Where is Mrs. Farmanfarmaian?” Zara said: “Shortly after the book came out, she left for Iran, because she felt finished with her work in New York and wanted to start some new projects in Iran.” After I read the remarkable story of Monir’s life, that statement started making perfectly good sense to me. Yes, she would start all over again, and no, her work isn’t done yet.

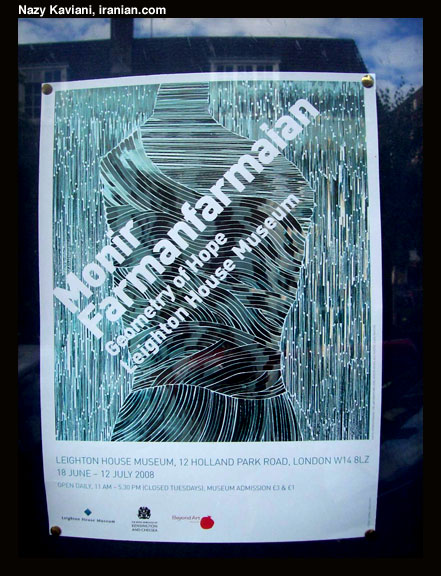

While on a short vacation in London this week, I came across Monir Farmanfarmaian’s exhibition, Geometry of Hope, at Leighton House Museum. I was delighted for the chance to see what this new work looked like. I wasn’t prepared for the effect the 84-year-old artist’s work would have on me. As I began to look at the different pieces, I could feel Mrs. Farmanfarmaian’s predicted “hope” building up inside me!

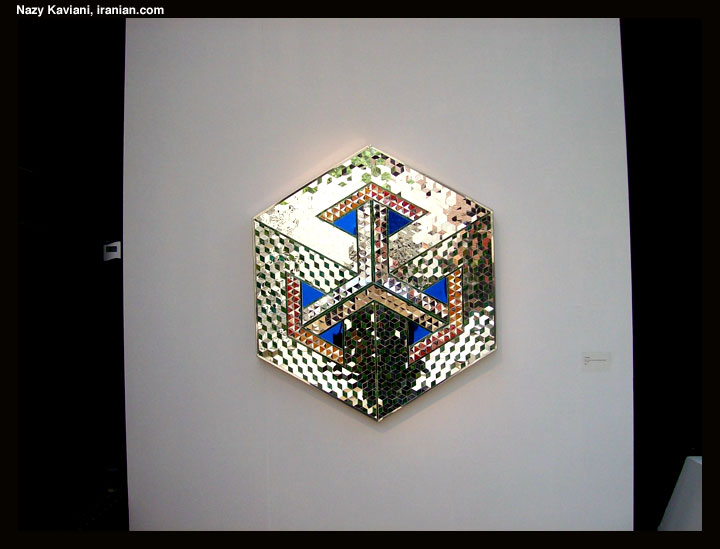

Iranians have a history-old love affair with mirrors. Aside from their practical value, mirrors are messengers of hope for Iranians, used in numerous daily or special rituals. We use them in our wedding ceremonies, at our Nowruz spreads, and as the first “guests” to arrive and bless our new homes along with a Koran. Sadly, mirrors are also used to decorate mobile structures called Hejleh, which are used to announce and mourn the death of young men in their neighborhoods.

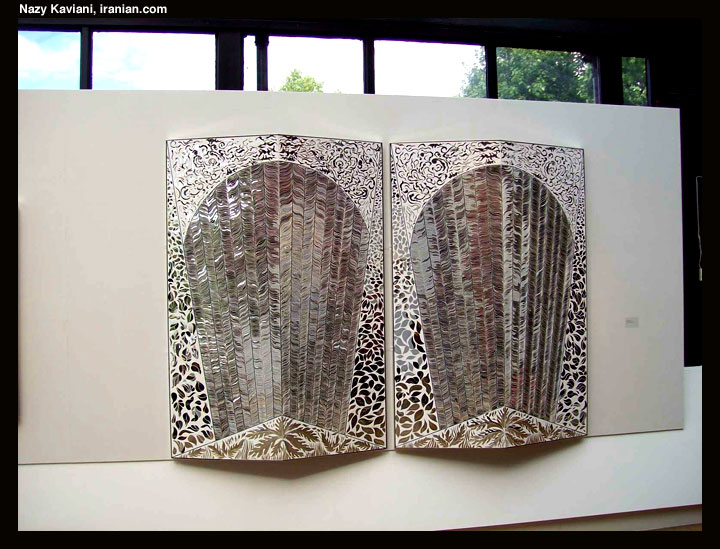

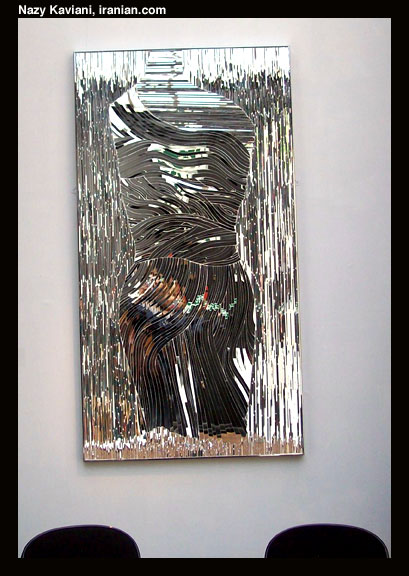

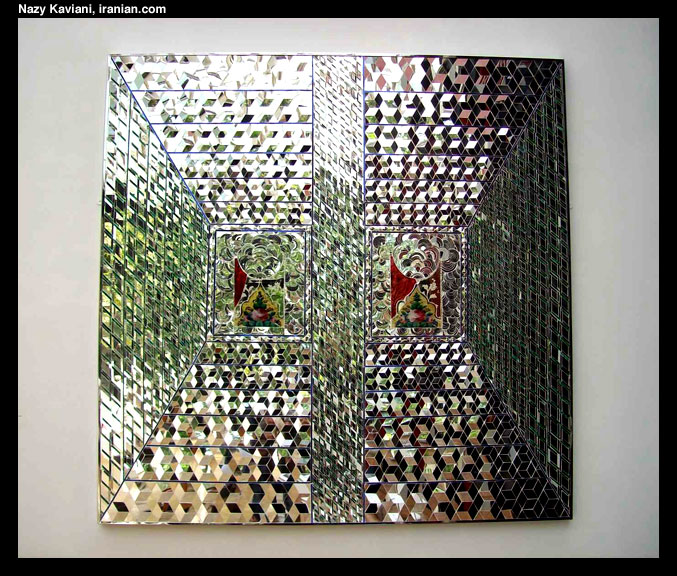

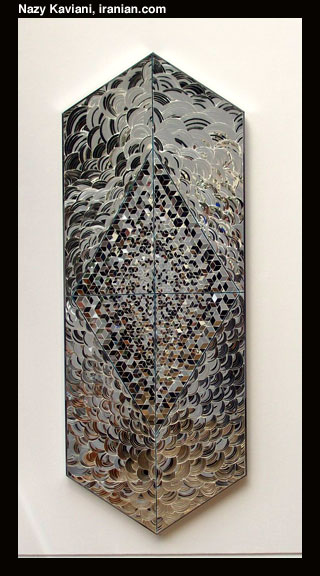

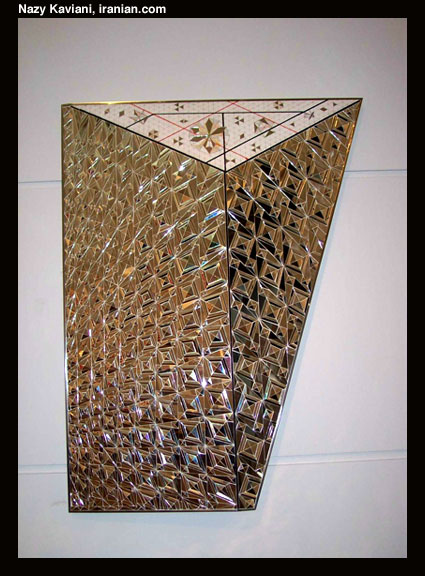

Mirrors are also used for decorating interiors of Iranian buildings. Some of Iran’s most intricately decorated structures and palaces contain “Ayeneh Kari” which is the art of cutting mirrors into small pieces and slivers, placing them in decorative shapes over plaster, creating artwork that is at once bright, reflective of light, colors and images, and expressive of beautiful patterns. Monir Farmanfarmaian’s inspiration and subject for her new collection has obviously been Iranian Ayeneh Kari.

I heard during my short stay in London that immediately after her arrival in Tehran, Monir employed several old Ayeneh Kari masters who worked with her to transform the many ideas and designs she had had in mind into reality. Since Ayeneh Kari is a less-fashionable decorative choice in many Iranian homes these days, it is feared that with the passing of this intricate artwork’s masters and artisans, the art form might die altogether. Monir Farmanfarmaian’s important contribution to preserving the work of those masters and artisans and hopefully teaching new apprentices in the process is an invaluable service to Iranian arts, a tradition this dynamic woman has set and maintained steadfastly since the 1960’s.

I spent a beautiful sunny afternoon in a gorgeous house-turned-museum, where the dance of light on the mirrors so beautifully cut and re-assembled in gorgeous shapes had filled the space with such energy and joy, it was hard not to feel hopeful! Mrs. Farmanfarmaian was right, she did have some important work to do in Tehran!