To the readers: the Farsi version of this and the upcoming episodes have been published in a local newspaper in Iran after omitting some of the names, sentences, and sections deemed unsuitable for local audiences. Even though, some authenticity have been lost in translation to English, I hope the meanings have remained unhampered.

Even though, it has been a long time since I was in high school, I still remember this always-applicable sentence from my Arabic textbook; “knowledge earned at young age is like carving in stone”, it lasts for lifetime. Indeed, what we learn during early stage of our life will be with us forever and will shape and nurture our personality, our beliefs, throughout our entire existence.

I spent my childhood years in a small, poor, Tehran neighborhood called, Maydan Mir. It was during these crucial years that my life story began to shape and the most memorable era of my life started and ended. I never forget that place. Sometimes, especially at night, when I cannot sleep, my mind, like a fast-flying falcon, flies far away over the sky of that community roaming the sky above the roofs of the houses in this community. When I think about it now, I realize that Maydan Mir was not the place for everyone. Only a small group of people, who were at the bottom of the social caste, lived in this community. They were connected not by a social club, a central air conditioning system, or a computer network, but through daily prayer at mosque, religious holiday’s ceremonies, and the mourning of the dead. Most of these people were farmers, construction workers, bus or carriage drivers, restaurant owners, tradesmen, or bazaar merchants. You could recognize how the hard daily work had taken its crippling tolls on most of these people who were prematurely handicapped. Facial, and hands, rough facial skin, hair prematurely turned white, darkened or paled face because of intense sun heat, were all the sings of debilitating daily work.

Even though my father was a farmer, there was no sign of any trees or garden in our house nor was any trace of life-enhancing amenities. Our yard, frankly, was not big enough for anything to grow. There was only a self-grown fig tree with no benefit for us except the dust on its leaves causing rashes on our skin, coughing, and itching. Our disoriented life in this house resembled the fate of the passengers of an automobile going down the hill with failed break system. Inability to control our destiny forced us to accept the idea that our fate was already determined and we had no choice but to submit to it.

My parents were totally unconcerned about the bleakness of the future awaiting them. Their living in this world was the preparation for the other. They indeed view their temporary life as the prelude for the eternal life after death. As a matter of fact, there were looking forward to the end of the mundane life as the joyous start of the eternal life. How could you wish otherwise if your life is like an extended suffering? They really believed that the world was like the prison for pious people. Justice and injustice, comfort or hardship, having or no having, victory or defeat, pride or humility, upward mobility didn’t seem to matter much to them. They had no admiration for anything except their religion so much so that I sometimes viewed them as the hostages to their own beliefs. They were like the soldiers living in a world in which permanent peace was guaranteed and nothing challenged their life and there was not anything to hope for. The good thing about my parents was that I didn’t have to pound my brain to understand them as their life was so simplistic and their thoughts so one-dimensional. Nonetheless, I always admire their integrity and devotion to the purpose of their living whether I totally agreed with it or not.

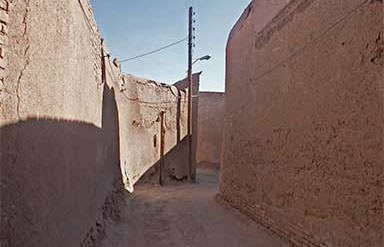

It was not a good time to be a kid. There was no sign of modernity in our neighborhood; life was simple, primitive and deprived. The basic necessities such as electricity, running water, radio, telephone were considered alien to us. Even asphalt was an unattainable luxury for our community. When you walked on the muddy surface of the narrow and long alleys during the months of winter, you could sinks into sticky mud up to your ankles. Not even one day went by without someone being injured from slipping and falling on slippery surfaces. There was no shortage of shortages for us, however, the most persistent one was the liquidity shortage.

The nameless alley in which our house was located was long and narrow. It was not too kids friendly because it was not suitable for any kind of fun and play. People who lived in our alley were all poor farmers with the exception of one family whose house was the very first one to your left when you enter the alley. The man of the house was a member of the clergy. For this reason we called him agha sar chooche-e as if there was no other agha in our alley. I remember when he came out of his house all the women who happen to be sitting and gossiping at the front of a house double checked their chador and made sure that they are covered properly. The tall and long muddy walls enclosed our alley on both sides. The length of these walls reminded me of my geometry teacher who use tell us that two parallel lines never intersect no matter how long you extend them. Even though the classical example of this concept was the rail roads, but for me the everyday example was these two walls. When you looked at them from the start of our alley, you could hardly see the end.

Unluckily, our house was at the very end if this alley. That meant that when it came to filling out our hose – a concrete in ground pond- with fresh water, we had to wait until everyone else had their chances. Every community around us had a person in change of channeling running water to the neighborhood through the steams, most of them muddy, usually after the midnight to make sure that all the human beings and animals are sleep and the possibility of contaminating the water was slim. He was called joob pa. Because of the fact that our house was last in line to get fresh water, we had to bribe him handsomely anytime we needed to fill out. Otherwise, we may not get our fair share of fresh water. As my father used to say; filling our hose with water was more difficult than amal omme davood, a very long and hard Shia prayer.

The only things that still connect me to that house are the memories, nothing else worth to hold on to. In today’s standards, our house was like a huge backyard shed situated at the end of an undeveloped plot of land. The house was so old build completely out of clay and mud with caved-in, or out, walls. No colorful object could be found in this house. Khaki was the theme of our interior decoration. The house had only two bed rooms, one was the place where we lived in, otagh neshiman, and the other one which was built on the top of a big hose was extremely humid and practically unlivable. Thanks God, for some reason, we decided to use the other room to live and sleep in. otherwise, who knows what would have happened to us from the long term exposure to moisture and humidity. Our bathroom which was called zaroori by my father was built at the far corner of the yard to keep us away from bad smell. Using this bathroom was really a sport, an art and washing your bottom afterward was a religious responsibility. We had to take turn in using it in the morning. That is how I learned Macarena dance! At the entrance of our house was a long roofed space called dallon. It was long and dark. The attic space at the top of dalloon was the place where we stored wheat and barely. The adjacent space was reserved to keep animal food for our caws and donkeys. We called it kaddon.

Our covered hose beneath our second bedroom was famous in the whole neighborhood because it was the source of drinking water for most of the families lived in this alley. Boys and girls used to come to our house with a jug or a pitcher to take their daily drinking water from our covered pond, a courtesy service extended to our neighbors free of charge. That gave me a chance to catch a glimpse of the cheeks in our neighborhood once a while! Because it was deep, covered, and dark; no one dared to swim in this pond. It was, therefore, immune from misuse by naughty kids. That gave our neighbors a false sense of assurance that the water they were getting was clean and drinkable. I must admit that our hose was actually the second most popular. The first one was the one in zan haji’s house. That was much bigger than ours. However, after her only son, Morteza, was drowned in it and died as a result, no one had the willingness or taste or to take water from it.

Under our only living/bed room there was a basement which was more frightening that Abu Ghraib prison. It was dark and so dusty that even cock roaches didn’t have the desire to make it their home. The only things you could in this basement were the very old farming tools many of them obsolete even in those days’ standards. At the other corner of our front yard there was a small room which was our kitchen. We called it matbakh, place for cooking in Arabic. Inside of it was so black that reminded me of the devil who is in charge of daily punishment for the worst of the sinners in hell! The soup and meat stew pots, dizi abghossht, were always boiling in our kitchen. I remember when I returned from school in evenings, I was really hungry and kept bugging my mother for food. Because it was too early for the family dinner, so she took a big peace of bread and dipped it into the boiling dizi and gave it to me. The absorbed floating fat made it so memorably delicious. As her daily routine, my mother had to boil a big pot, ghazghoon, of milk every day to make yogurt. Selling yogurt to the only local grocery shop in our neighborhood was one the key sources of income fro our family. She had to carry the heavy pot of milk many stairs up to matbakh. She had to seek help from jaddeh sadat many times over.

The only entry door to our house had its own unique personality. It was decorated with heavy hardware. The door was so heavy that only a big strong man can fully close it. There was no lock or any other safety system to protect our belongings in our house. As a matter of fact, we didn’t need such a system. Finding anything worth stealing in our house was as scarce as finding a pro IRI in this web site! The computerized! locking system of our house was called caloon doneh. The only thing you need to open the entry door, if it was locked, was an L-shaped piece of wood board which was like a generic key that can open almost every door in our alley. Once a while someone was bitten by snake or scorpion as he/she tried to reach deeply into caloon doneh to open the door. For this reason, it was one of the things I was really afraid of. Some of scorpions in our house were more frightening than ghashieh snakes that live only in hell.

Our house didn’t have a postal address because our alley didn’t have any name and our house did not have any number. The final mail deliverer in our neighborhood was Mirza Abbas Ali, the only micro-grocer in our quarter. Almost all the postal letters or packages were addressed to him who had the pleasure of delivering them, and reading them, to the intended addressees. He was, eventually, aware of the content of almost all the letters sent to us because he was one of the few who could read. Most of residents, especially the older ones, could not read or write. It was Mirza Abbas Ali’s social and moral duty not only to deliver but to read the letters to the final recipient. I was so thrilled when we had a letter because I loved to save the stamps.

One of our next door neighbors was another poor farmer, Mashdi Asghr. Despite continuous loud irritating coughing, he didn’t want to give up the habit of smoking tobacco pipe, chopogh. After his first wife died a few years back, he decided to marry again, tajdid farash, so to speak. This time, to a younger woman, as we used to say; saroon piri, maareke giri. The outcomes of his fist marriage were a few children. His oldest daughter, Zahra, was physically smaller than than the other girls of her age. For this reason she was nicknamed as Zara moushe! Just to differentiate her from other Zahras. Giving nicknames, often despising, to people was usual in our town.

As a matter of fact people were more recognizable by their nicknames than by anything else. Zahra used to come to our house to learn Koran from my mother. Even though my mother was formally illiterate, she could read Koran fairly correctly, just like many other individuals in our neighborhood. She had a few other girls like Zahra enrolled in her Koran’s exclusive class. Zahra was a smart student. I remember, she finished, amme joase, a very brief version of Koran prepared for freshmen, in a few weeks. The joy of her parents from such accomplishment was immense and parental. As a show of appreciation, they brought a big jug of goat milk for us, 100% pasteurized! Teaching Koran to others was a moral duty of every believer, like my mother, and a tuition-free educational service for the kids, especially female, in our neighborhood. My mother had no expectations of pecuniary reward. However, the parents of the students often sent my mother in-kind tuitions such as: wheat or barely, yogurt, dried fruits, mohr and tasbih, and the souvenirs they brought with them from holy places. I heard that Zahra was later killed in a traffic accident. God bless her soil.

I was fascinated by watching these innocent female angles sitting dawn in a row at the front of rahl, a decorative book holder made out of wood, and moving upper part of their bodies in harmony while reciting the verses of Koran together. While they had no understanding of the meaning of what they were reading, they were mesmerized by the sheer power of the words and the rhythm of the short verses they were chanting in harmony >>> PART 2