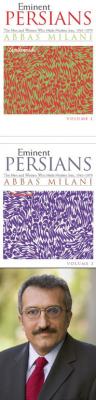

Eminent Persians

The Men and Women Who Made Modern Iran, 1941-1979

Volumes One and Two

by Abbas Milani (Author)

Syracuse University Press , 2008

As the 25th anniversary of the Islamic Revolution approached, Abbas Milani realized that very little, if any, attention had been given to the entire prerevolutionary generation. Political upheavals and a tradition of neglecting the history of past regimes have resulted in a cultural memory loss, erasing the contributions of a generation of individuals. Eminent Persians seeks to rectify that loss. Consisting of 150 profiles of the most important innovators in Iran between World War II and the Islamic Revolution, the book includes politicians, entrepreneurs, poets, artists, and thinkers who brought Iran into the modern era with brilliant success and sometimes terrible consequences. Abbas Milani is the Hamid and Christina Moghadam Director of Iranian Studies at Stanford University where he is also a research fellow at the Hoover Institution.

PURPOSES MISTOOK

Politics in Iran: 1941–1979

Politics in modern Iran has been dominated by protracted battles between competing models of politics and society. One formative battle has been between advocates of a secular Iran, its laws emanating, at least ostensibly, from the will of the people, and supporters of an Islamic Iran, ruled not by law, but by sharia and personal fiat, and legitimized not by popular sovereignty but by divine anointment. In this contested history, a bewildering variety of political movements, ideologies and forms of government have appeared on the horizon. Movements as far apart as Nationalism, Constitutionalism, Marxism, Islamic Fundamentalism, Social Democracy, Islamic Liberalism, and Fascism have each found powerful Persian advocates. Forms of government as different as Oriental despotism and Islamic theocracy, “guided” democracy and authoritarianism, and finally, liberal democracy have all been tried at some moment of Iran’s modern history.

The effort to create political parties has also yielded surprisingly varied structures. The first attempt to create political parties in the 1940s helped foster a kind of democratic experience, and the two-party system of the late 1950s was often described by the Shah as an experiment in “guided democracy.” At the same time, the Shah himself had brought both parties into existence, and had placed at their helms a succession of trusted loyalists. From Manuchehr Egbal and Assadollah Alam to Yahya Adl and Amir-Abbas Hoveyda, each had their turn as the leader of a party. What he had created, the Shah felt entitled to dissolve. In 1975, the Shah dismissed all political parties, replacing them with a single party he called the Rastakhiz or Resurgence Party.

Nearly all the elements of this varied collection of political structures can also be found in the west. In Iran, however, they have often assumed unusual forms, shaped by the vagaries of a long imperial history, by the dictates of geography—particularly proximity to most of the world’s known oil supplies and to the Soviet Union, the now-almost-forgotten “evil empire” of the Cold War—and finally, by the hegemony of a particular form of Islamic culture called Shiism.

The conflict between modernity and tradition did not arrive with Shiism, but has underlain Iranian politics from the start of the twentieth century. Beginning with the Constitutional Revolution of 1905–07, modern Iranian politics has struggled with modernity, and the temptation to emulate the West not just in politics, but in every aspect of culture. Seen as an episode in this continuing struggle, the 1979 Islamic revolution was not the first but certainly the most successful attempt to turn back the historical clock and dismantle what little progress Iranian society had made toward political modernity.

From a broader historical perspective, the same revolution appears one of the twentieth century’s greatest political abductions. Ayatollah Khomeini and his cohorts co-opted a democratic popular movement that enjoyed the near-unanimous support of the country’s urban population, and instead of a democratic polity, created a pseudo-totalitarian theocracy where nearly all power rests in the hands of an unelected and despotic “spiritual leader.”

This abduction was the more daring, and the more anachronistic, because it took place just as the world was seeing an end to despotic and totalitarian regimes. In the mid-1970s the world had begun witnessing what social scientists now term the “third Wave” of democracy. Regimes based on ideology—long considered the most pernicious form of despotism—were in their death throes. Liberal democracy, with some form of market economy, was beginning to emerge as the victor in the “culture wars” of the Cold War era.

In defiance of this important global development, in contravention of the democratic aspirations of the Iranian people, and in spite of a long tradition of “quietist” Shiite theology, embodied in the person and practice of Ayatollahs Hoseyn Boroujerdi and Seyyed Kazem Shari’atmadari—a tradition that discouraged the clergy from any claim to political power, and that, in the months after the fall of Saddam Hussein in Iraq, was brilliantly exhibited in the personality and practice of Ayatollah Sistani—Ayatollah Khomeini used the chaos of the revolution, the organizational weakness of the democratic forces, the weakness, illness and vacillations of the Shah, the policy confusion in the Carter Administration’s handling of Iran, and finally, the West’s continued fear of Soviet expansionism, to create an anachronistic Islamic state in Iran. Neither the dynamics of his success, nor the foundation of the lives of the eminent men and women of Iranian politics, can be understood, or explained, without some appreciation for the overall contours of modern Iranian history.

Decoding the Iranian Past

Deep-rooted cultural obstacles have hitherto hindered the serious and impartial study of Iran’s political history. A dearth of archives, memoirs, journals and biographies, and the prevalence of a Manichean view of history, where the cosmos is torn between the forces of good and evil, have been among the obstacles on the road to a clear, accurate understanding of Iran’s political history.

Another obscuring factor, one that has discouraged attention to the role of multiple individuals in shaping modern Iranian political history, has been the cult of hero worship. The belief in the formative role of “great men” has traditionally shaped the Iranian view of history. The dominance of this view has meant that the few reliable biographies, and much of the historical narrative, written to date have focused on a few important figures only; as a result, the lives of hundreds of men and women who actually shaped the contours, and determined the course, of Iran’s modern political history, have attracted little or no attention. This section of Eminent Persians is intended to fill in and integrate this incomplete and fragmented historical landscape.

Of course the cultural distrust of individualism is not the only reason for this fragmentation or for the failure to fully chronicle or appreciate the role of the myriad men and women who actually shaped modern Iran’s politics. Iranian culture has long had a propensity for Messianic thought; it has had a need for a Savior, or Mahdi, to arise and deliver salvation. History shows that messianic milieus are fertile grounds for the development of conspiracy theories; one easily begets the other. In fact, a propensity toward conspiracy theories is often the secular corollary of a messianic proclivity. Shiism, the dominant form of Islam in Iran, is at least partially predicated on the idea that the twelfth Imam—the Mahdi—will reappear after his long absence, and with his return, all injustice and want, all inequality and suffering will end. Indeed messianism and conspiracy theories—both prevalent in Iran—have much in common. In both, a force outside society, beyond its redress and review, shapes the fate of that society; in both, individual responsibility is abjured in favor of some cosmic or foreign force; in neither do individuals with their foibles, or societies with their failures, bear any responsibility for the calamities that have befallen them. In both, the power of the conspirator correlates negatively with the sense of enfranchisement on the part of the populace. In both, order and meaning are imposed upon a world that appears terrifyingly chaotic and meaningless.

Informed and self-assured citizenries do not need the balm of conspiracy theories. If people lose their faith in the redemptive power of the messiah—as they often do when societies secularize—and do not concurrently develop faith in their own powers as citizens to determine their own political life, then lapsed messianism easily morphs into belief in conspiracy theories.

>>> Eminent Persians available from amazon.com