To the sound of an abba rustling over the floor, a white turban bobs in and out of view. A pulpit militant is surrounded by his entourage, awaiting the arrival of the Supreme Leader. At the sight of Ayatollah Ali Khamenei, the crowd parts, yielding every inch of the space to every movement of the white-turbaned Misbah Yazdi. He proceeds forward with ardent agility and swift strides only to fling himself on the ground. Humbly, he kisses the Supreme Leader’s feet, refusing to rise until he has dutifully paid his utmost respect to the Faqih (the Guardian).

A few years ago, Ayatollah Misbah Yazdi shocked the Islamic Republic’s inner circles with this performance conducted in front of flashing cameras and rolling camcorders. Publicly, the conservatives admired his selflessness but envied his prudence behind closed doors; the moderates snickered and dismissed the news of the event with curt replies. The shock, however, must not be attributed to the publicly captured humility of any ayatollah towards the Supreme Leader. On the contrary, such scenes are entirely common and dully expected. What caused the jolt was not the act itself but the stature of the man behind the act, his existing ominous authority and decisive clout, and more importantly, the absence of any apparent gain bestowed upon him.

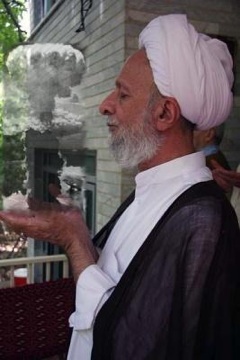

To an outside observer, Ayatollah Misbah Yazdi might appear as a foolish opportunist seeking favors from the Supreme Leader. Nothing could be farther from the truth. In fact, the white-turbaned pulpit militant needs anything but tokens of boon from the Faqih. For thirty years, Ayatollah Misbah Yazdi and brethren have incorporated an Islamic realm at the center of which sits the vision of a nuclear Iran, a dream that was born forty-two years ago to another man.

The Pahlavi Dynasty

In 1967, Mohammed Reza Pahlavi, the Shah of Iran, bought a five megawatt research reactor from the United States of America. Several Western powers including the United Kingdom, France, and Germany supported Shah’s nuclear energy program and provided reactors and technical training to young ambitious Iranian scientists. After signing and ratifying the Nuclear Proliferation Treaty in 1970, the Shah of Iran initiated a clandestine nuclear weapons foray parallel to the civil program.

Before long, Iran’s explicit intention to covertly develop weapons grade fuel and technical know-how to design and manufacture nuclear weaponry was reported by CIA and eventually by other intelligent services around the world. Although Western powers were aware of Iran’s clandestine nuclear program, subsequent U.S. administrations looked the other way while the last Persian monarch dreamed of attaining the role of Persian Gulf protectorate for his nation in the near future.

In the momentous summer of 1975, two weeks before the beginning of fall semester, forty two Iranian students arrived at Cambridge, Massachusetts and registered at the nuclear engineering department of MIT. The Nixon-Ford administration had instructed the United States Atomic Energy Commission to pave the way for their success. This elite group of young men was chosen by Dr. Kent Hansen, Professor of Nuclear Engineering, to attend one of the United State’s most prestigious schools in order to foster the first generation of nuclear scientists in Iran. In exchange, the Iranian government endowed the Massachusetts Institute of Technology with an unspecified sum of money in addition to furnishing all the required expenses. Three years later, after an intense course of study in the master’s program, the unholy union between MIT and the Shah of Iran gave birth to thirty five nuclear science graduates.

The Revolution

After the fall of the Pahlavi Dynasty in February of 1979, Iran’s civil and covert nuclear programs lay dormant until Hojateah, a secretive and ultra conservative Shi’a society, attempted to revive the endeavor. Emboldened by the rise of an Islamic theocracy, Hojateah set out to capture key political and administrative positions throughout the country in order to gain control over Iran’s local and national affairs. Unlike other active political groups yearning to capture headlines, Hojateah leaders were rarely seen or heard of publicly. Instead, they diverted their attention and abundant energy to build an elite army of faithfuls equipped with ironclad spiritual devotion and temporal nuclear weaponry.

In the years immediately following the revolution of 1979, under the leadership of its founder, Sheikh Mahmoud Halabi, Hojateah refused to recognize Imam Khomeini as such and ridiculed his aspiration to be the lone emissary of the Hidden Imam. Since its inception in 1953, Hojateah leadership has motivated its members by advocating an apocalyptic vision of the world, appearing to be resolutely awaiting the arrival of the twelfth Imam of Shi’a. This ploy has been most effective in mobilizing the Shi’a faithful against the Bahá’í religion. Not surprisingly, the brutal oppression of the Bahá’í faith has been and remains to this day one of the top priorities of this ultra conservative Shi’a society.

Oddly enough, Imam Khomeini disapproved of Hojateah and its apocalyptic clamor and ordered its dissolution in 1984. Faithful to the rank and file, the leadership of Hojateah once again went underground in order to escape yet another era of persecution but continued to bide its time to resurface. In the ensuing months, the secretive society was brutally crushed by Imam Khomeini until the Islamic Republic became entangled in a military stalemate with Iraq.

The Plan

In 1981, Saddam Hussein, with the implied blessings of the international community, unleashed his army’s chemical and biological wrath on innocent Iranians for the first time. As the war progressed, the images of mangled bodies flashed on every television set around the country, and the death toll began to rise exponentially. By 1985, the talk of ending the war plagued Imam Khomeini’s inner circle. Spurning the peaceful advances of Iran’s moderate clergy, with a singular nod of his head, the Supreme Leader eventually paved the way for the hardliners to cement their power in the key positions of the government. In exchange, the war with Iraq was to be continued indefinitely.

When the news reached the top lieutenants of Hojateah, a blazing flash of relief trickled down their spine. Their nuclear aspirations would no longer be hindered by a regime that was now entangled in two fronts: fighting a war against an outside aggressor while crushing political opponents within. The stage was set for the conception of atomic akhond.

Despite leaving the crumbling façade of moderation behind, Imam Khomeini’s distaste for the secretive society remained intact. Consequently, instead of making a direct attempt at seizing power, the prudent leaders of Hojateah relegated their ambitions to four main projects while awaiting Imam Khomeini’s inevitable demise due to old age.

The first project was to obtain nuclear weapons technology from the international black market in order to build a uranium enrichment facility and purchase centrifuge components. In 1986, Dr. Abdul Qadeer Khan, the father of Pakistan’s nuclear program, visited Iran to lay the foundation for the illicit nuclear weapons technology transfer. By the end of 1987, Iran had established a large uranium enrichment facility using gas centrifuges identical to Dr. Khan’s Pak-1 model.

The tightly interlaced web of international black market responsible for the proliferation of nuclear technology to Iran spans the globe. From American companies to Israeli businessmen, from Dubai computer corporations to German middlemen, from Malaysian government to Dutch exporters, they have all been implicated in defying the international restrictions and legal bans. The world at large has been complicit in selling nuclear devices to the Islamic Republic. The collective deeds of this proliferation ring have nourished and hence fostered the full development of atomic akhond in the womb of our motherland.

The second project focused on gaining control over the politico-economic, Mafia-like, authoritarian force creeping into existence since 1979. Prior to the establishment of the Islamic theocracy in Iran, Shi’a clergy’s lifeline was supported by the donations of devout Muslim businessmen who voluntarily endowed 20% of their profits to local mosques and charity organizations. After the revolution, various Islamic foundations (bonyads) were formed to seize and redistribute the accumulated wealth of apostate capitalists. Before long, a handful of bonyads became multinational conglomerates and commercial enterprises generating billions of dollars in annual revenue. Once bonyads became more than slush funds for mullahs and their cronies, Hojateah took notice and sought its share of the pie together with the real levers of authority to sustain the flow of income.

The third project was to build the necessary infrastructure to identify, recruit and retain upper and middle class Iranians with strong religious convictions. For the success of this endeavor, Hojateah leadership had to literally look down the street towards Tehran’s Alavi Institute. Since its inception in 1956, the only objective of the Alavi Institute has been to breed an intellectual religious elite whose sole purpose is to contend with and pacify the secular erudite of Tehran.

True to its original goal, the admission committee of the Alavi Institute has opted for the cream of the crop through intense background checks, entrance examinations, and a discriminating interview process. In the last thirty years, by funneling unlimited funds to the Alavi Institute, Hojateah has successfully created a fraternity of intellectuals fortified with impenetrable religious core and passion. Amidst the ever changing face of the contemporary world, the Alavi Institute has become the modern bastion of Shi’a resilience and morphing image.

To sustain the long term needs of these elite members, societal security and safety nets together with lavish luxuries have also been conjured. For example, the largest and most specialized hospital in Iran, Khatam ol Anbia, has been fortified with an isolated floor that caters only to the upper echelons of Hojateah and their families. Trustworthy doctors are summoned to treat the admitted patients who still live with the fear of being poisoned or murdered unexpectedly, a fate that abruptly ended the lives of Shi’a Imams centuries ago.

The fourth project was to create a cobweb of blood brethren whose intertwined interests will forever bind them together. Through carefully orchestrated marriages and appointments, the key political, military, and financial positions in the Islamic Republic of Iran are awarded to the members of one big, happy family at the head of which sits the secretive, ultra conservative Shi’a society, accountable to no one and immune from the reaches of mere mortals.

Conclusion

Today, destiny continues to pause at the crossroads of history, contemplating the fate of our nation. Meanwhile Iranian political activists are grimly plunging deeper and deeper into a tailspin, attempting to unravel the phenomenon of atomic akhond. Some have joined the neo-conservative choir of “bomb, bomb, bomb Iran.” Others are emboldened by the prospect of a nuclear homeland, puffing their chests with national pride. Yet, there are those who are utterly bewildered and are admittedly unprepared to confront the new face of a formidable foe. Many prescriptions have been written, and much energy has been devoted to the topic.

Similar to thirty years ago, Iranian political activists have been caught off guard by the resourcefulness, sheer survival skills, and momentum of the Shi’a machinery. Intellectuals from all walks of life have been reduced to mere pawns in the hands of mullahs who continue to receive the brunt of jokes and ridicules from the secular community. Once again, the joke is on us: Come hell or high water, the Islamic Republic of Iran will attain nuclear armaments. The question that still remains unanswered is this: What can an ultra conservative Shi’a government do with nuclear weaponry?

An intelligent answer to this question necessitates not only a deep understanding of the past and the present political environment in Iran, it also demands a non trivial knowledge of the Shi’a history and its political ambitions. Only through a concerted effort, it becomes possible to step away from the existing hype and fear mongering of Western analysts and media, the so-called experts who not until recently were aware of the centuries-old chasm between Islam’s two major sects.

Historically, the Shi’a clergy has proved to be the consummate survivor, the nimble, cunning power player outlasting its ideological and political opponents, constantly adapting to the turmoil of any era through ruthless pragmatic maneuvering. From the very outset of the current nuclear initiative, Shi’a clergy was preparing for turbulent times accurately predicted by Hojateah leadership. Nonetheless, we must not allow the profound paradox that exists between Shi’a’s prophetic forecast, on the one hand, and mullahs’ aspirations for survival, on the other hand, cloud our judgment.

Although the hardliners’ vision of tomorrow is shrouded in secrecy and apocalyptic rants, one thing is clear: Those who run the Islamic Republic of Iran have no desire to die. Contrary to their end-of-days rhetoric, they crave an everlasting earthly life to savor the fruits of their labor. Along the same lines, the apocalyptic ramblings of Hojateah together with Ahmadinejad’s pious messages dropped down Jamkaran’s holy well are for the public consumption in order to rekindle the Shi’a fervor amongst the rank and file. This end-of-days oratory is meant to mend the broken pieces of Shi’a emissary shattered by thirty years of corruption, thievery, mass murders, cruelty, and greed.

Similar to the war with Iraq, atomic akhond will use the attainment of nuclear technology to rally the masses and infuse much needed pride into the hearts of an entrapped nation yearning freedom from the dark ages of inquisitors. Simultaneously, the secular voices within the society will be isolated and their nationalistic urges pacified. Furthermore, with the accomplishment of nuclear technology and weaponry, Shi’a intellectuals will forever interweave their legacy with the glory of scientific achievements albeit stolen or purchased. Last but not least, in the international arena, the possession of nuclear weaponry will eventually solidify the Islamic Republic’s rank amongst reluctant foreign powers and will serve as a deterrent factor towards outside aggressors.

At the end, while Iranian political activists are debating the merits of supporting or opposing the dawn of atomic akhond, Hojateah is preparing to leap forward into the next chapter of its history, a fate furtively perceived to be inevitable but uniquely exposed by a kiss: After all, Ayatollah Misbah Yazdi’s kiss was not a trivial attempt at self-effacement. That kiss was the ultimate affirmation of a Faqih’s celestial power and the final indication that Hojateah has its eyes on the office of the Supreme Leader.

For Iran’s moderate Shi’a clergy, that kiss might have also been the kiss of death…