Dystopian predictions of Ray Bradbury in the science-fiction novel Fahrenheit 451 not withstanding, it turns out that enhancing communication technologies can empower rather than enslave the masses. Indeed, the past century of Iranian history, complete with its revolutions and democracy-building, has been intertwined with the evolution of mass media.

The campaign for the 12 June presidential election is no exception.

During the 1905 to 1911 Iranian Constitutional Revolution that led to the establishment of a parliament, the country experienced a period of unprecedented debate in the form of a flourishing press. For example, the revolutionary poet and agitator Nasim-e Shomal single-handedly wrote and hand-printed a newsletter published under his name, which translates to “The Northern Breeze”. He is known for standing by the main gate of Tehran’s Grand Bazaar with his bushy black beard and flowing clerical robes, distributing his constitutionalist agitprop.

During the Islamic Revolution of 1979, it was the now-obsolete cassette tape that slipped through the iron cage of the state-dominated news media and carried Ayatollah Khomeini’s sermons to his mass following.

More than 25 years later in the 2005 presidential elections, Iranian reformers used SMS messages and blogs to encourage votes against the block of supporters that swept current President Mahmud Ahmadinejad to power. Although they had little success, the reformist bloggers who actively followed the elections found themselves in the ranks of Iran’s opinion makers and intellectuals.

Today, the lack of primaries in the presidential elections cuts the active election period to less than a month and the flurry of activity common during this one month has only been exacerbated by the exchange of information and mobilisation made possible by online technologies.

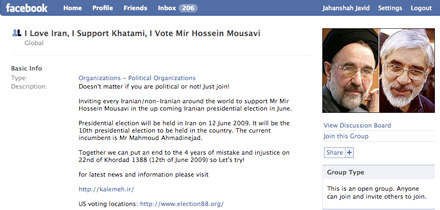

Readers of Iran’s early blogs have become bloggers in their own right and are using the popular online application Facebook to promote their preferred candidate.

Behzad Mortazavi, the head of the campaign committee for leading opposition candidate Mir Houssein Mousavi, claimed in an interview with the Financial Times that new technologies are being used in Mousavi’s campaign because “they have the capacity to be multiplied by people themselves who can forward Bluetooth, e-mails and text messages and invite more supporters on Facebook.”

Facebook was previously used in Iran primarily for sending virtual gifts and silly personality tests to friends, and more recently to connect with Iranian expatriates. But currently, Iranians’ Facebook and Twitter profiles are abuzz with political campaigns. The support for candidates on these online forums is revealing: Ahmadinejad has some 10,000 Facebook fans and is featured on several Facebook pages with supporters not only in Iran, but also from all over the Muslim world. Meanwhile, the former prime minister, Mousavi, has approximately 40,000 fans on the site.

And touting the campaign slogan “Change”, veteran politician and cleric Mehdi Karroubi – the “dark horse” candidate – has several fan club pages on Facebook, including the “Ask Stephen for the ‘Colbert Bump for Karroubi'” page, which urges US political satirist Stephen Colbert to endorse Karroubi in an effort to boost his popularity.

Reformers – who support increased political freedoms and a more robust democracy – agree that another four years of Ahmadinejad’s foreign policy and economic swings would be intolerable. On Facebook, this sentiment takes the shape of a ubiquitous banner: “No vote is a vote for Ahmadinejad.”

These Facebook users appear to be encouraging people to vote and pre-empting a possible boycott campaign, such as the one that was blamed for Ahmadinejad’s 2005 victory.

This campaign forum is not without problems. On 23 May, the Iranian government blocked access to Facebook without explanation. It was restored a few days later, but the fact that the government would ban it demonstrates the site’s perceived importance in shaping popular opinion. And in the lead up to this week’s elections, Facebook is functioning more as a means of mobilising like-minded relatives and friends in support of candidates than a forum to woo others away from their opposing candidate.

But the passion and active political involvement of millions of young Iranians, using modern means of communication to encourage change, would surely have brought a smile to Nasim-e Shomal’s lips.

AUTHOR

Iranian-born Ahmad Sadri is the James P. Gorter chair of Islamic world studies at Lake Forest College and a columnist for the Iranian newspaper, Etemade Melli. This article was written for the Common Ground News Service (CGNews). Source: Common Ground News Service (CGNews), 9 June 2009, commongroundnews.org. Copyright permission is granted for publication.