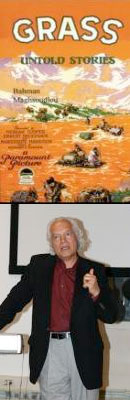

Grass: Untold Stories

by Bahman Maghsoulou

Mazda Publishers (2009)

This book not only tells the story of the film Grass, the pioneer 1924 still-documentary on the migration of the Bakhtiari tribe from their summer to winter quarters in Southwest Iran, but also the lives of three American adventurers who made the film.

The book describes, in detail, and on the basis of a variety of sources, including the memoirs and books written by the three Americans adventurers, their life experiences, most importantly, their unusual adventure in making the film Grass.

The first half of the book deals with their lives before leaving for Iran and the second their extraordinary adventure with the Bakhtiari migration.

The author traces the life of each one of the three, from family background to education till they embark on foreign adventures during the Great War. They came from different family backgrounds. The woman, M. Harrison, whose idea was to make the adventurous film, was raised in a rather well-to-do family, while the two men, future “King Kong” producers Merian Cooper and Ernest Schoeksack, grew up in not-so well-to-do families. But they had one thing in common: their desire for adventure.

While Harrison ended up working during her adventures as an undercover agent, in guise of a journalist, for the US Military Intelligence Department (MID)—a cover that has often been used by the secret services in different, the classical example being that of Kim Philby, the British Communist who worked as a right-wing journalist in Spain during the Civil War in order to join the British Secret Service as a Soviet spy, ending up as an SIS agent under the cover of a journalist for The Economist in Beirut before having to take flight to the Soviet Union.

Cooper, an aviator to begin with, ended up as film-producer in Hollywood. Schoedsack, a run-away boy in school, became a cameraman with considerable abilities.

Harrison traveled to many countries on assignment as a journalist, including Germany during the revolutionary period after the end of the Great War. She then moved to revolutionary Russia, again in guise of a journalist, reporting on the political situation in a country in revolutionary upheaval, providing information that the West needed badly in order to understand what went on in Soviet Russia and make policy accordingly. She was finally arrested and imprisoned under very difficult conditions. Her story of incarceration, related in this book, is very fascinating and gives a glimpse of the life under the early Soviet period in Russia. Interestingly, she met another American, John Reed, the founder of the American Communist party, who was also in Moscow for the second congress of the Communist International as well as in Baku for the interesting First Congress of the Peoples of the East, where he was infected by typhoid and died as a result in Moscow. As a journalist, Harrison used her acquaintance with Reed, also a journalist by profession, to visit the headquarters of the Communist International in order to obtain any information she could lay her hands on. Finally released in conjunction with the American Relief program to famine-stricken Soviet Russia, she went back there again, this time through the Far East. By then, she had become a well-known journalist in America. One would have to read Grass to learn about the formidable and daring undertakings of this unusual woman.

Cooper was no less dangerously daring. He first became a small-town journalist, but later joined the National Guards, newly formed by President Wilson during the Great War, and then the American military strike force in France. He ended up fighting on the side of Polish forces under Pilsudski engaged in a life-and-death battle against Soviet Russia. Finally, he was captured by Bolsheviks forces and incarcerated under very difficult, barely sustainable conditions.

In the meantime, Harrison had met Cooper in Warsaw, and the latter had, in Vienna, come to know Schoesack, who had been working in the US Air Force. Thus, the three adventurers eventually came into contact with one another.

The acquaintance between Harrison and Cooper turned out to be very useful for the latter, who, in prison under a false name, was helped by the former from outside the jail. He knew that, if his true identity were discovered, a terrible fate would await him. Finally in April 1921 Cooper managed to make a daring escape from the Soviet prison, where had had been suffering a terrible ordeal. After fourteen days of harsh walking he arrived in Riga, Latvia where he was safe.

After their return home, each of the three undertook different project before coming up with the idea of making a documentary on the migration of the Bakhtiaris from their summer to winter quarters. The idea was suggested by a friend of Harrison’s at the State Department, Harry Dwight, who had reportedly known the Middle East.

Although there is mention of choosing the Kurds in Anatolian region of Turkey for their film, after some senseless adventure leading to disappointment in that country, the trio left for Khuzistan, the oil producing region of the country, which was under British Petroleum’s control, whence they were to go to the Bakhtiari region. They studied travelogues by former British reconnaissance officers, who spoke of Bakhtiaris as “arrant robbers,” and “free booters,” living under a “feudal system” as well as their “brutality.” Having acquired this idea of the Bakhtiaris, it is not clear what interest the three American adventurers had to risk such a dangerous undertaking at a time none of the three had any money, the funding, some $10,000, having eventually been raised by Spy Harrison.

To get to Ahwaz, and whence to the Bakhtiari region, they received aid from the American consul in Shiraz, George Fuller, and British consul in Ahwaz, Captain Peel. They were introduced to the Governor of the region and a Bakhtiari “Prince,” who took upon himself to facilitate their trip across the Zagros Mountain during the migration of the Bakhtiaris. (By the way, it is curious the Bakhtiari chiefs introduced themselves as “princes” to their guests!)

Their traveling with the migrating Bakhtiaris took nearly two months across snowbound Zagros, during the months of April and May 1924. Their description of some Bakhtiari customs and habits must be the first full account of that annual migration related by anyone—accounts that must be of interest to anthropologists. In their description of the Bakhtiaris, one comes across pejorative and racist remarks that portray their feeling of superiority toward the “savage” Bakhtiaris, who had not invited them to come and share their harsh life with them. For instance, once Spy Marguerite Harrison fell ill and the migration of the whole tribe, including children and newborns, was held up for two days in the cold mountain climate and “deep glacial snow” of about 4,000 meters altitude so that she could recover; yet, this is what she had to tell about them:

“Our leave-taking [from the Bakhtiaris] was unaccompanied by regrets on my part or Shorty’s [Schoesack’s]. Merian [Cooper] was the only one of our party who developed a liking for the Bakhtiari[s]. They were not a loveable or interesting people—hard, treacherous, thieves and robbers, without any cultural background, living under a remorseless feudal system, crassly material, and devoid of sentiment and spirituality. Their two outstanding qualities were an arrogant pride of race and a contempt for physical weakness.

Even Haidar [their guide] whom we saw every day never displayed the slightest sign of friendliness toward us, and took advantage of us whenever he could. Truly, as Amir Jang [the Bakhtiari chieftain who, with his family, in addition to exploiting the poor tribesmen, received $65,000 a year from the colonial British oil company,] said, his people were ‘Bears.’” (pp. 233-4)

Forgetting the wild deserts of her own country, like Arizona and Nevada, she also complained of the “yellow bounding spiders on the ground where we slept;” adding “I prefer to be among tigers”! (208) All this in spite of their “hospitality” toward uninvited “guests”! One wonders whether, given that anywhere in the Wild West one would have had to live in similar conditions, this comment, like many others, does not spring from outright racism! Surely, the reading the accounts of two British colonialists, Henry Layard’s Early Adventures and Sir Rawlinson’s piece in the Journal of the Royal Geographic Society, must have influenced these Americans with colonial prejudice, Americans who must have viewed the Bakhtiari “nonwhites” in the same light as the “redskins,” whose lands and pastures the British colonies had confiscated.

Given the long history of the profession of Marguerite Harrison as a spy for the American Government, the intriguing question is whether the real motive of Harrison, who enticed the other two adventurers, was not a continuation of her mission for the US government at a time it was trying to get hold of oil resources in a region known for its rich sources of that vital energy. There is nothing in the documentation in the book that would validate such a hypothesis. Nonetheless, the assassination of the American Consul in Tehran Robert Imbrie a month after the departure of the Trio by religious fanatics, rumored to have been tele-commanded by the British in fear of competitors in Iran, resulting in the abandonment of American attempt to seek a concession for oil exploration in Iran, is worth studying.

The author speaks of the success of the film that was shot during the two months, as well as the history of later remakes of it decades thereafter under different conditions, after Reza Shah’s “modernization” had ruined the traditional life of these pastoralists. In this connection, it is interesting to recall what one of the clan leaders named Rahim Khan, who had received some Western education in Beirut, told the Americans:

My people are content as they are. Why should I try to change them? They are happy after their [own] fashion; they live as their fathers have lived for centuries before them. The time will come when civilization will be forced upon them, and I doubt if they would be happier for it. I have had an education and it has only made me discontented with my life here. It has done me no good. (p. 179)

He may have said this for ulterior motives, as rationalization of the exploitation of the pastoralists. In retrospect, however, one may see a certain truth in their unhappiness by way of “forced civilization” upon them.

Finally, be it said that it would have been preferable to correct the original transliterations by the Americans of Persian or Arabic words in their stories.

Anyone interested in cinematographic documentaries of “primitive” tribal life, tribal customs and ways of life, Iranian anthropology, as well as the strange lives of three American adventurers must read this book and obtain a DVD of the original documentary.

AUTHOR

Cosroe Chaqueri is a retired academic/historian living in Paris.