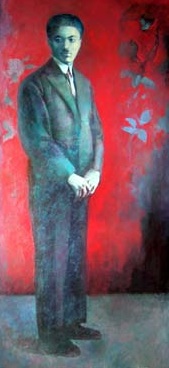

Sadeq Hedayat was born on 17 February 1903 and died on 9 April 1951. He was descended from Rezaqoli Khan Hedayat, a notable 19th century poet, historian, and historian of Persian literature, and author of Majm‘ al-Fosaha, Riyaz al-‘Arefin and Rawza al-Safa-e Naseri. Many members of his extended family were important state officials, political leaders and army generals, both in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, including Mokhber al-Dawleh, Nayyer al-Molk I (Hedayat’s grand-father), Sani‘ al-Dawleh, and Mokhber al-Saltaneh, who was prime minister between 1928 and 1933.

Hedayat is the author of The Blind Owl, the most famous Persian novel both in Iran and in Europe and America. Many of his short stories are in a critical realist style and are regarded as amongst some of the best written in 20th century Iran. But his most original contribution was the use of modernist, more often surrealist, techniques in Persian fiction. Thus, he was not only a great writer, but also the founder of modernism in Persian fiction.

Yet both Hedayat’s life and his death came to symbolize much more than leading writers would normally claim. His personality and psychological moods, his intellectual flare, his cultural values, his social rebelliousness towards virtually every established order in society including that of the opposition, and, ultimately, his sense of alienation from existence itself, placed him in a unique position among modern Iranian intellectuals. He emerged as an embodiment of the most sophisticated – but also the least patient and most radical – social and cultural Europeanism of his time. He still towers over modern Persian fiction. And he will remain a highly controversial figure so long as the clash of the modern and the traditional, the Persian and the European, and the religious and the secular, has not led to a synthesis and a consensus.

Tragedy in Greek classical literature is a personal drama; comedy, a shared experience. It is lived and acted by the hero (or anti-hero) in silence and solitude. It ends up in failure, defeat, death. But it does so in full honour. It was lived – among others in the history of modern European art and literature – by Byron, Shelley, Keats; by Rousseau, Baudelaire, even Dostoevsky; by Beethoven, Schumann, Tchaikovsky. Many a genuine Persian mystic must have experienced something similar, though records of this are less precise. Hedayat lived and died a tragic life in this classical sense.

Having studied at the exclusive St. Louis French missionary school in Tehran, Hedayat went on a state grant to in Europe, spending a year in Belgium in 1926-27, a year and a half in Paris in 1928-29, two terms in Reims in 1929, and a year in Besançon in 1929-30. He had been sent to study architecture with the obligation of working for the ministry of roads and communications, but he did not like the subject and eventually (in April 1929) obtained permission to read French literature in a teacher training context. Still, he did not finish the course and gave up his scholarship and returned home in the summer of 1930. This provides a clue to his personality in general, and his perfectionist outlook to performance in particular, which sometimes resulted in nervous paralysis.

Back in Tehran, Hedayat became the central figure among the Rab‘eh or Group of Four, which included Mojtaba Minovi, Bozorg Alavi and Mas‘ud Farzad, but had an outer belt, including Mohammad Moqaddam, Zabih Behruz and Shin Partaw. They were all modern-minded and critical of the literary establishment both for its intellectual traditionalism and classicism, which they mocked as ‘grave digging’ and ‘the science of fossils’, and for its seeming subservience to the state which, paradoxically, beat the drums of Ayrianism and modernity. They were also resentful of the literary establishment’s contemptuous attitude towards themselves, and its exclusive hold over academic posts and publications. Decades after the formation of the Rab‘eh, Farzad wrote the following epitaph for its members:

Hedayat died and Farzad was wasted (mordar shod)

Alavi went leftwards, and was arrested (gereftar shod)

Minovi took the right path and was rewarded (puldar shod),

which incidentally reflects the subsequent loss of friendship between Farzad and Minovi.

Back in the 1930s, Hedayat drifted between clerical jobs, and had a brush with the censors, until 1936, when he went to Bombay at the invitation of Sheen Partaw who was then an Iranian diplomat in that city. Having just returned from France in 1930, he wrote to his friend Taqi Razavi in Paris about his appointment in Bank Melli, then the central bank as well as a commercial bank, with a measure of contentment if not joy. Only eight months later he wrote again:

As far as my own work is concerned I’d better be silent. Every day, all the year round, I am being suffocated in the God-forsaken Bank. It’s a filthy and mechanistic kind of existence.1

Shortly afterwards he wrote optimistically about the possibility of opening a bookshop; “It doesn’t take much capital”, he wrote, “and we intend to lancé [sic] ourselves by means of publicité [sic]”.2 This daydream did not turn into reality and we find him writing in October 1932 that he has resigned from the Bank and is working at the Office of Trade. He did not last there either and was unemployed for some time when he was given a translator’s job in the foreign ministry. He left a few months later when his boss asked him why all the verbs in his translations were in the subjunctive mood. He said he could only think of subjunctive verbs in the afternoons. “Why don’t you translate in the mornings, then”, his boss asked. “In the mornings I’m not in a translating mood at all”, Hedayat answered.3 It took him some time to find a clerical job in the state Construction Company. Predictably, he ran foul of the official censors and was made to give a pledge not to publish again. That was why when he later issued the first, limited, edition of The Blind Owl in Bombay, he wrote in the title page that it was not for publication in Iran, predicting the possibility of a copy finding its way to Iran and falling into the hands of the censors.

He was unhappy and wished to travel abroad. In 1935 Jamalzadeh invited him to go to Geneva as his guest. He sold all his effects but he could not obtain foreign currency due to the official foreign exchange policy. A year later, on a visit to Tehran from Bombay, his writer friend Sheen Partaw who was a diplomat there invited him to go as his guest to Bombay and so he resigned his job and went there in 1936. In the meantime he had fallen foul of the official censor and had given a written pledge that he would not publish again.4

In the year in Bombay, he learnt the ancient Iranian language Pahlavi among the Parsee Zoroastrian community, wrote a number of short stories and published The Blind Owl in fifty duplicated copies most of which, through Jamalzadeh, he distributed among friends outside Iran. From there he corresponded with his friends in Europe, especially with Jamalzadeh, Minovi and Jan Rypka, the Czech scholar of Persian literature, telling them about his new Pahlavi studies and complaining about his situation in life. In a letter to Rypka, for example, he wrote once:

I’ve been learning Pahlavi for some time…though I don’t think it would do me much good in this or the other world. Everyone tries to make a living by some sort of trade. For example, somebody draws the arc of the letter nun well, another memorises classical verse, and somebody else writes flattering articles, and till the end of their days they enjoy a living from what they do. I can now see that whatever I’ve so far been doing has been useless.5

He was back in Tehran in September 1937, although he had returned with great reluctance and simply because he did not feel justified in continuing to depend on his friend’s hospitality in Bombay. He went back to the Construction Company for a short while, and then returned to Bank Melli, this time as a trainee. ‘I am busy’, he wrote to Minovi, “adding and subtracting and doing some other dirty jobs, and if they’re not satisfied, I get the sack”.6 But a year later he resigned his post and became a member of the newly instituted Office of Music, and an editor of its journal, Majelleh-ye Musiqi, The Music Magazine. It was literary work among a small group of relatively young and modern intellectuals, including Nima Yushij, founder of modernist Persian poetry. He might well have regarded that as the most satisfactory post he ever had.

It did not last long. After the Allied invasion of Iran and abdication of Reza Shah in 1941, the Office of Music and its Journal were closed down, and Hedayat ended up as a translator at the College of Fine Arts, where he was to remain till the end of his life. He also became a member of the editorial board of Parviz Khanlari’s modern literary journal, Sokhan, an unpaid but prestigious position. Even though the country had been occupied by foreign powers, there were high hopes and great optimism for democracy and freedom upon the collapse of absolute and arbitrary government. The new freedom – indeed license – resulting from the Shah’s abdication led to intense political, social and literary activities. The modernist trends were centered on the newly-organized Tudeh party, which was then a broad democratic front led by Marxist intellectuals, although by the end of the 40s it had turned into an orthodox communist party. Hedayat did not join the party even in the beginning, but had sympathy for it and had many friends among Tudeh intellectuals, including Bozorg Alavi, Khalil Maleki and Ehsan Tabari, as well as younger men such as Jalal Al-e Ahmad. For a time, he also wrote for Peyam-e Naw, the journal of VOKS, the Society of Irano-Soviet cultural relations.

But the party’s support for the Soviet-inspired Azerbaijan revolt in 1946, which led to intense conflicts within it, and the sudden collapse of the revolt a year later, deeply upset and alienated Hedayat from the movement.7 He had always been a severe and open critic of established Iranian politics and cultural traditions, and his break with radical intellectuals made him a virtual émigré in his own land. It made no small a contribution to the depression in the late 1940s, which led to his suicide in 1951. A measure of his growing anger, frustration and depression may be gauged from many of his letters of that period. He wrote to Jamalzadeh in 1947, ‘I’m very tired and lack interest in everything. I somehow go through the days, and every night – after soaking myself in drink – bury myself, and spit on my grave as well. But the other miracle that I perform is that I get up in the morning and start all over again.’8 A year later, in October 1948, he explained to Jamalzadeh that he had ‘lost the habit of writing’ and was ‘sick and tired of everything’. It was a reflection of his total isolation when he added that ‘besides, in our life, environment and everything else there’s come a terrifying rift such that we can no longer understand each other’s language’. He then burst out:

I neither have the stomach to complain and belly-ache, nor can I deceive myself, nor have I got the guts to commit suicide. It’s just a kind of vomity condemnation which I have to bear in a filthy, shameless, fucking environment.9

For some time his close friend Hasan Shahid-Noura’i who was serving as a diplomat in France had been encouraging him to go to Paris. There were signs that his depression was deepening by day. He was extremely unhappy with his life in Tehran, not least with his life among intellectuals, many of whom were regularly describing him as a ‘petty bourgeois demoralizer’, and his work, as ‘black literature’. Others were publishing books and articles against him in the guise of biographical essays and literary criticism. He wrote of them and their works to Shahid-Noura’i:

One must ready oneself literally for anything in this shameless and stinking environment. On the other hand, they’re absolutely right. Whatever they may say and do [to me] isn’t enough. When one’s surrounded by the rabble and sons-of-whores, and doesn’t join them in thieving, duplicity, fraud, sycophancy and lack of shame, one’s naturally guilty. And if he doesn’t like it, he can lump it.10

Here in these letters, beneath and beyond Hedayat’s apparent cynicism, iconoclasm, etc, we may observe, not far from the surface, his anger and despair, his acute sensitivity, his immeasurable suffering, his continuously darkening view of his own country and its people, and his condemnation of life as it is, rather than it ought to be. Through the letters perhaps more than his fiction one may see the three faces of his predicament, the personal tragedy, the social isolation and the universal alienation. “Thank God you’re familiar with the black dog of my mood and know that I find letter-writing a tremendous effort, and that the inertia is unintentional.”11 “I don’t just regard myself as a subject of the kingdom of the Rose and Urine [Gol-o–Bawl; cf.Gol-o-Bolbol]; I also feel like a man condemned…I only wonder what a shameless son-of-a-whore I must have been to be able to carry my own carcasse [sic] in this son-of-a-whore set-up till this moment.”12 Again, “What an accursed, base and rotten country we’ve got, and what malevolent and infernal people it has! I feel that all my life I’ve been a plaything in the hands of whores and sons-of-whores.”13 And again, “Throughout life we have been a bête pourchassé [sic] Now the animal has been traquée [sic]…only a few reflexes [sic] stupidly go on doing their work. And our crime is that we’ve been living for too long.”14 There: the personal, the social, and the universal.

The specific contribution of Hedayat’s own country and society to the agitation and alienation of his sensitive soul is not in doubt, but the wider universal predicament was perhaps more deeply ingrained. Hedayat wrote two of his most important works in the mid to late 40s when he was regularly corresponding with Shahid Nura’i. And much the same that may be observed in his letters may also be discerned from these two imaginative works. In his Peyam-e Kafka (The Message of Kafka), which is largely his own sober, measured and studied message in the guise of a review of Kafka’s life and literature, there is neither a mention nor even an allusion to Iran and the Iranians; ‘the message’ is global, even universal. Tup-e Morvari, The Morvari Cannon, on the other hand, is profusely uncomplimentary to Iran and the Iranians, where the erstwhile (romantic) nationalist author of Parvin the Sasanian Girl, Maziyar, etc, leaves little to imagination about the unhappy aspects of Iranian culture and history. But the main message of that black satire is still global, universal: it condemns all religion; all politics; all existence. Hedayat laughs through this, and shouts through the other. Yet both Peyam-e Kafka and Tup-e Morvari – which are some of his best literature, and his literature on life, and on his own life – reflect and expose the same anger, the same despair, the same hatred. 15

Hedayat went to Paris in December 1950 and committed suicide four months later. He was hoping to find peace in Europe and live there for as long as he could. He had very little money and post-war Europe was expensive everywhere. His friend Shahid-Noura’i had an illness from which he never recovered; he died virtually on the same day as Hedayat. In any case, he could not get him a clerical job in his own office as Hedayat had expected. There was no question of obtaining a French work permit; he was even finding it difficult to extend his visitor’s visa. He tried to go to London or Geneva where his friends Farzad and Jamalzadeh lived and worked but did not succeed. He tried but did not manage to extend his sick leave from the College of Fine Arts.

Suddenly, his brother in law, General Razmara, prime minister and chief of the army was assassinated in Tehran amid popular rejoicing, confronting his family with a great catastrophe, and robbing them of any special social and psychological support which they might have given him at that moment of despair. Two weeks later, on 8 April 1953, he took sleeping tablets and turned on the gas cooker in his little flat-let. Contrary to lingering legends he had not gone to Paris to commit suicide. He had gone there to avoid it. In the end he found every possible door securely locked except the prospect of immediate return to his old situation in Tehran now amidst the catastrophe which had befallen his family. He took his life. 16

In a letter which he wrote in French to a friend in Paris four years before his last visit, he had said:

The point is not for me to rebuild my life. When one has lived the life of animals which are constantly being chased, what is there to rebuild… I have taken my decision. One must struggle in this cataract of shit until disgust with living suffocates us. In Paradise Lost Reverend Father Gabriel tells Adam ‘Despair and die’, or words to that effect…I am too disgusted with everything to make any effort; one must remain in the shit until the end. 17

Ultimately, what he called ‘the cataract of shit’ proved too unbearable for him to remain in it till the end.

Hedayat’s fiction , including novels, short stories, drama and satire, written between 1930 and 1946 comprises Parvin Dokhtar-e Sasan (Parvin the Sasanian Girl), Afsaneh-ye Afarinsh (The Legend of Creation), “Al-bi‘tha(t) al-Islamiya ila’l-Bilad al- Afranjiya” (Islamic Mission to European Cities), Zendeh beh Gur, (Buried Alive), Aniran (Non-Iranian), Maziyar, Seh Qatreh Khun (Three Drops of Blood) , “Alaviyeh Khanom” (Mistress Alaviyeh), Sayeh Roshan (Chiaroscuro) Vagh-vagh Sahab (Mr. Bow-Vow), Buf-e Kur ( the Blind Owl), “Sampingé” and “Lunatique” (both in French,) Sag-e Velgard (Stray Dog), Hajji Aqa, Velengari (Mucking About), and Tup-e Morvari (The Morvari Cannon) .

His literary studies – including folklore, essays, travelogue, translations and reviews – written between 1921 and 1950, consist of Roba‘iyat-e Khayyam, (Khayyam’s Quatrains), Ensan va Haivan (Man and Animal), “Marg” (Death), Favayed-e Giyah-khari (The Uses of Vegetarianism, 1927), “La Magie en Perse”, Isfahan Nesf-e Jahan (Seeing Isfahan), Awsaneh (folk tales and popular beliefs), Neirangestan (also popular beliefs and rites, and superstitious practices), Gojasteh Abalish ( Abalish the Damned), Karnameh-ye Ardeshir-e Babakan (The Record of Artaxerexes son of Babak,), Gozaresh-e Gaman Shekan (Report of the Renegade), Zand-e Vahman Yasn (Commentary on Vahman Yasn), all of them translations from the Pahlavi texts; “Goruh-e Mahkumin” (Kafka’s ‘Penal Colony’, translated with Hasan Qa’emiyan), “Maskh” (Kafka’s ‘Metamorphosis’, translated with Hasan Qa’emiyan), Jean Paul Sartre’s short story “The Wall”, Peyam-e Kafka (The Message of Kafka), and numerous folk tales, short translations and reviews posthumously gathered by Hasan Qa’emiyan in Neveshteh-ha-ye Parakandeh-ye Sadeq Hedayat (Sadeq Hedayat’s Scattered Writings, 1955).

His published letters, which make up an important part of his literature, are numerous, and are to be found in Sokhan, April-May 1955, Mahmud Katira’i (ed.) Ketab-e, Sadeq Hedyat, Mohammad Baharlu (ed.) Nameh-ha-ye Sadeq Hedayat, Bijan Assadipour (ed.) Daftar-ha-ye Honar, vol. 6, 1996, and Nasser Pakdaman (ed.), Hashtad o daw Nameh-ye Sadeq Hedayat beh Hasan Shahid-Nura’i.

Commenting briefly on Hedayat’s prose, in its basic elements, his prose is based on Jamalzadeh, but it has its own distinct form, and it is suitably adjusted to the content, be it psycho-fiction, satirical fiction, critical fiction, essay, criticism and translation. It is plain, easy to read and understand, shorn of literary embellishments, using common expressions where appropriate, and avoiding complex words of Arabic origin. The most developed Persian prose styles since World War II are syntheses (to different degrees) of contributions made by Dehkhoda, Jamalzadeh, Kasravi, and Hedayat. Yet, occasionally (and sometimes frequently) Hedayat slips in his grammar and use of words. This is evidently more frequent in his psycho-fictions than other works – and most striking in The Blind Owl – sometimes giving the impression that, in its formal presentation, the work has been drafted hastily; the impression that he wrote many of his psycho-fictional works quickly, so to speak, to get them off his chest. In his literary devices, the lyrical forms or figures of speech, Hedayat is particularly good at the use of metaphor and imagery, which are at their best in The Blind Owl. But he does use other literary devices as well.18

I have classified Hedayat’s fiction into four analytically distinct categories, although there is some inevitable overlapping between them: romantic nationalist fiction, critical realist stories, satire, and psycho-fiction. 19

First, the romantic nationalist fiction. The historical dramas, Parvin and Maziyar, and the short stories “The Shadow of the Mongol” (Sayeh-ye Moghol), and “The Last Smile” (Akharin Labkhand) – are on the whole simple in sentiment and raw in technique. They reflect sentiments arising from the Pan-Persianist ideology and cult which swept over the Iranian modernist elite after the First World War. “The Last Smile” is the most mature work of this kind. Hedayat’s explicit drama is not highly developed, and he quickly abandoned the genre along with nationalist fiction. But many of his critical realist short stories could easily be adapted for the stage with good effect.

The second category of Hedayat’s fictions which I have suggested, his critical realist works, are numerous and often excellent, the best examples being “Alaviyeh Khanom” (Mistress Alaviyeh) which is a comedy in the classical sense of the term, “Talab-e Amorzesh” (Asking for Absolution), “Mohallel” (The Legalizer), and “Mordeh-khor-ha” (The Ghouls). To varying degrees, both satire and irony are used in the stories, though few could be accurately described as satirical fiction.

They tend to reflect aspects of the lives and traditional beliefs of the contemporary urban lower middle classes with ease and accuracy. But, contrary to views long held, they are neither “about the poor or downtrodden”, nor do they display sympathy for their types and characters. Indeed, among the author’s works, they contain the least explicit judgment. It is clear that the attitude and way of life of the types in this group of his works are alien to the author’s own class culture and social and intellectual outlook, but it is also clear that, to the people whose lives are thus fictionally dissected and exposed, life is very much worth living. Wretchedness and superstition is combined with sadness, joy, hypocrisy and, occasionally, criminal behavior. Characters are common; situations, realistic; language, authentic. This was in the tradition set by Jamalzadeh (though he had more sympathy for his characters), enhanced by Hedayat, and passed on to Chubak and Al-e Ahmad in their earlier works. 20

Coming to the third category of Hedayat’s works, Hedayat’s satirical fiction is rich and often highly effective. He was a master of wit, and wrote both verbal and dramatic satire. It takes the form of short story, novel as well as short and long anecdotes. Almost invariably, all of his satirical fiction ridicules one of the three powerful establishments (with occasional overlapping): The literary establishment; the religious establishment; and the political establishment. The author applies his knowledge of these establishments and their ways, his own negative personal judgment of them, and his remarkable wit in producing fiction, which is always funny and sometimes hilarious. They hit hard at their subjects usually with effective subtlety, though sometimes outright lampooning, denunciation and invective reveal the depth of the author’s personal involvement in his fictional satire.

The literary establishment is mocked and ridiculed, for example, in the “Ghaziyeh-ye Ekhtelat-Numcheh” (The Case of the Gabbing), effectively and – allowing for the inevitable elements of caricature – with reasonable accuracy. In the short story, ‘The Patriot’, even the names of real-life models of the leading literary-political figures may be deduced both from the story and from their fictional forms. Hedayat’s satirical fiction is paralleled by some of his reviews of the literary establishment’s works – full as they are of merciless jibes – such as his reviews of Farhang-e Farhangestan (the Dictionary of the Literary Academy) – and of a contemporary edition of Khamseh-ye Nezami (Nezami’s Five Romances). The damage is at its worst when he exposes the authors’ silly mistakes.

The best example of Hedayat’s religious satire is “Islamic Mission to European Cities”, although the subject comes up often enough in his satirical as well as critical realist fiction. It is, at once, a mockery of the contemporary cultural underdevelopment of Islamic lands, and an indictment of the motives of some worldly religious types.

Hajji Aqa is the longest and most explicit of Hedayat’s satires on the political establishment. Superficial appearances and critical propaganda notwithstanding, it is much less a satire on the ways of the people of the bazaar and much more of a merciless attack on leading conservative politicians. Indeed, the real-life models for the Hajji of the title were supplied by two important old-school (and, as it happens, by no means worst) politicians.

In a couple of his other political satires Hedayat uses the technique of allegory, the best example being “Qaziyeh-ye Khar Dajjal” (The Case of Anti-Christ’s Donkey) which is a damning satirical allegory on political events in the country between 1921 and 1941. The Morvari Cannon, his last satire, brings together all the three – political, literary and religious – strands with brilliance as well as vehemence, reflecting more even than his former satires the author’s intense anger and alienation. 21

Hedayat would have had a lasting and prominent position in the annals of Persian literature on account of what I have so far mentioned. What has given him his unique place, nevertheless, is his psycho-fiction, of which The Blind Owl is the best and purest example. This work and “The Three Drops of Blood” are modernist in style, using techniques of French symbolisme and surrealism in literature, of surrealism in modern European art, and of expressionism in the contemporary European films, including the deliberate confusion of time and space, which had been anticipated in one or two Renaissance and post-Renaissance works such as Rabelais’s Gargantua and Laurence Sterne’s Tristram Shandy. But most of the other psycho-fictional stories – e.g. “Zendeh beh Gur” (Buried Alive), “Arusak-e Posht-e Pardeh” (Puppet Behind The Curtain), “Bon-bast” (Dead End), “Tarik-khaneh” (Dark Room) and “Stray Dog” – use realistic techniques in presenting psycho-fictional stories.

The appellation “psycho-fictional”, coined by this author in the mid-1970s to describe this particular genre in Hedayat’s literature, does not render the same sense as is usually conveyed by the well-worn concept and category of “the psychological novel”. Rather, it reflects the essentially subjective nature of the stories, which brings together the psychological, the ontological and the metaphysical in an indivisible whole. 22 It comes close to Jung’s, rather than the Freudians’, view of the relationship between psychology and literature. Jung dismisses fiction consciously based on psycho-analytical models as being somewhat artificial and uninteresting, and focus’s on the unintended influence of psychology in the poetry and fiction. Some post-modernist critics, notably Jacques Lacan, have taken a similar view of the subject, though the seminal contribution of Jung has seldom been acknowledged.

It was noted that Hedayat’s critical realist stories are about the lives, not the people of his own class and culture, but of those of the traditional urban lower middle classes, and they contain the least explicit judgment by their narrators and the author. On the other hand, most of his psycho-fiction are about the people of modern middle classes and contain sometimes very strong judgments about their ways, values, morals and behavior. 23 In my analysis of women in Hedayat’s fiction, I have shown how the view of women in the psycho-fictions is essentially different form the critical realist stories. 24

Hedayat’s psycho-fictional stories are macabre – sometimes, as in The Blind Owl, reflecting the primeval chaos – and, when the story ends, at least a man or a woman, or even a cat or a dog dies, commits suicide, is killed or otherwise disappears from existence. But there is much more to them than a simple plot of abject failure. There is crushing, insufferable, fear without clear reason; there is determinism of the hardest, least tractable and most fatal variety; there is sin without Sinai, guilt without transgression; there is Fall with no hope of redemption; there is punishment without crime; there is vehement condemnation of the mighty of the earth and the heavens.

Most human beings are no better than rajjaleh (rabble), and the very few who are better, fail miserably to rise up to reach perfection or redemption. Even the man who tries to ‘kill’ his nafs, to mortify his flesh, or destroy his ego, in the short story “The Man Who Killed His Ego” ends up by killing himself; that is, not by liberating but by annihilating his soul. Women are either lakkateh (harlot), or they are Fereshteh, that is, angelic apparitions who or which wilt and disintegrate upon appearance, as in the case of “the ethereal woman” in The Blind Owl, and “the puppet” in “Puppet behind the Curtain”, though this is only true of women in the psycho-fictions, women of similar cultural background to the author, not those of lower classes in his critical realist stories. There is the almighty fear of “an inherited burden”. There are hints – never quite open – at incest and/or incestuous desires. There is the alienation of the man from women, whom he does not know at all and has never loved in any successful contact of the flesh; women whom the psycho-fictional anti-heroes despise for what they believe they are, and long to love and cherish for what they think they ought to be. “The rabble”, both man and woman, are filthy – treacherous, hypocritical, disloyal, superficial, profit-seeking, money-grubbing, slavish, undignified and ignorant – because they are far from perfect. 25

Yet the effect is by no means entirely negative. There may not be any hope through the pages of these fascinating, absorbing and gripping stories. But there is an ideal which reconstructs itself through the destruction. Death may be offered as the answer, but it is offered in a plea for unrealized love, warmth, friendship, fellow-feeling, faithfulness, honor, authenticity, integrity, decency, knowledge, art, beauty; for whatever humans have eagerly and hopefully striven for and never quite realized. The large and seemingly unbridgeable gap between Appearance and Reality, between the Real and the Reasonable, between what there is and what there ought to be, between man and God, wears out the man and leads him to death as the only honest way out. Yet, it is precisely that gap which he wishes to close, and that honesty which leaves him no choice.

The plot of The Blind Owl, as its psycho-fictional content, is an advanced synthesis of Hedayat’s earlier psycho-fictional stories, but especially “Puppet behind the Curtain” “The Three Drops of Blood”, “Buried Alive”, “The Man Who Mortified His Flesh” (or The Man Who Destroyed His Ego), which – once again, in parts – finds expression in later works such as “Stray Dog”, “Dark Room”, “Dead End” and “Tomorrow”, and the two short stories he wrote in French, Lunatique and Sampingé.26

The novel is in two parts. Part one is the ‘contemporary’ story of the narrator and the angel, who wilts and dies upon appearance, and is cut up by the narrator and buried with the aid of the old hunch-back, the narrator’s fallen self. This, in part two, turns out to be an idealized summary re-experience of the story of the narrator and the harlot – the angel’s fallen self – in the ‘ancient past’, which ends up by the narrator, disguised as the wretched old man, killing her by pushing the same kitchen knife ‘somewhere in her body’, either – if the copulation has been complete – in order to destroy the sacred source which he has thus violated, or else as a phallic instrument to make up for his failure. He ‘returns’ to the ‘contemporary’ world to find the old hunch-back running away with the Ray jar – the symbol of continuity – and feeling the weight of a dead corpse on his chest. The man fails to become perfect; the woman fails to become an angel. There is no perfect love of the flesh; and there is no hope of sublime elevation.27 Given both the psycho-fictional quality of the story as well as the use of modernist techniques in presenting it, it is naturally open to various readings and interpretations, as it has indeed been to a few so far, and is evident from a number of chapters in this volume. The rich imagery, other literary devices and cultural symbolisms make it possible to offer even more diverse interpretations than otherwise. But many of these tend to represent aspects of the work in its various layers, not the story as a whole.

Much speculation has been made on the possible sources and ‘affinities’ of The Blind Owl. 28 To search and discover identifiable sources for works of art is an ancient occupation. And the discovery of such sources does not by itself reduce the value of a piece of work in the slightest. Some great world literature have identifiable sources and precedents, including Ferdawsi’s Shahnameh, Shakespeare’s Hamlet, Racine’s Le Cid and Goethe’s Faust. It cannot be doubted that modern Persian fiction as such as founded by Jamazadeh and Hedayat owe a great deal to modern Western fiction, itself going back no more then three centuries, since such fiction writing did not exist in Persian before the 20th century. Kafka, Sartre, Nerval, Poe, among others, even Buddhist traditions, have been named as sources for The Blind Owl. The Buddhist hypothesis does not bear examination. The Blind Owl was first published (in a limited edition) in 1936, before Sartre’s first work, La Nausée. Hedayat became aware of Kafka and his works long after that. There may be ‘affinities’ with them as also with Nerval, Rilke, Poe and many others; there are occasionally resemblances of ideas and expression, and in the case of Rilke’s Notebook the resemblance of a passage in The Blind Owl is uncanny; but none of them may be described as a source. 29

The Blind Owl is a modernist novel. Written in the general framework of modern western fiction and using modernist techniques, it addresses matters which are Persian, western as well as universal. It is a contribution to world literature based on both Persian and European cultural and literary traditions.

As a man born into an extended family of social and intellectual distinction, a modern as well as modernist intellectual, a gifted writer steeped in the most advanced Persian as well as European culture, and with a psyche which demanded the highest standards of moral and intellectual excellence, Hedayat was bound to carry, as he did, an enormous burden which very few individuals could suffer with equanimity, especially as he bore the effects of the clash of the old and the new, and the Persian and the European, such that few Iranians have experienced. He lived an unhappy life; and died an unhappy death. It was perhaps the inevitable cost of the literature which he bequeathed to humanity.

NOTES

For an extended discussion of the above points see Katouzian, Darbareh-ye Buf-e Kur-e Hedayat: 6 and 7.