“Innocence is to be presumed, and no one is to be held guilty of a charge unless his or her guilt has been established by a competent court.” — Article 37, chapter III of the Constitution of the Islamic Republic of Iran

Thirty-one years ago, a few months after the 1979 Revolution, the generals and close associates of the Shah, including his long time PM Amir Abbas Hoveyda, were shot to death without trial. The crowds cheered. When the father of the Rezai brothers, was asked to fire the shots, he refused. He was not a killer even though three of his own sons, members of the Mujahedin-e Khalq, had been killed under the Shah.

One of those generals was Hassan Pakravan who had long been retired at the time of his execution. Pakravan had spared Khomeini’s life in the 1960’s when he went to the Shah and asked for a special decree to reduce Khomeini’s sentence. (He and Khomeini used to meet for lunch each week). Pakravan was not allowed access to a lawyer and the charges against him were vague. Around the same time, Faroukh- Rou Parsa, the Shah’s Minister of Education, became the first woman executed for “spreading corruption among the youth.” PM Mehdi Bazargan, dismayed and deeply troubled about the killings, went to see Khomeini to ask him for clemency for the 85-year-old General Matbouei. In response, Khomeini said, “this class must be eradicated.” And so he was executed too.

One day, many years ago, I entered my father’s room. Bed-ridden, he could hardly move, but alert of mind, he would still read and follow the news in Iran. I saw him crying. I asked “why are you crying baba”? He told me, “because I just read about the execution of the Shah’s officials.” I said, “but weren’t they guilty? Were you not in prison six times during that period only because you belonged to the National Front?” He said, “still, they should have had a fair trial, with attorneys present, and be given prison terms.” I sighed. My father was right.

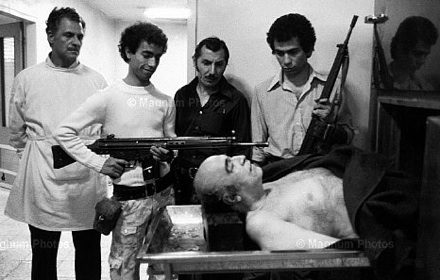

Once it began, the carnage never stopped. The mass executions at Evin have been well documented. The new regime eliminated those they disagreed with. In Kurdistan, summary executions took place; young men–future Pasdaran–shot to death many Kurdish revolutionaries. The new judges, endowed with aba and turban rather than knowledge and judicial education, took over the judiciary and started handing down execution orders. Khalkhali, nicknamed the ‘hanging judge,’ was one of the first ones. He was the judge, the jury and the executioner. When asked, -what if they were innocent? –he responded by saying, if they were innocent, they will go to heaven!

Few people objected to the execution of the Shah’s associates. A few expressed their dismay about the killing of Fedayeen and Mujahedeen. Many more voiced their horror at the mass executions in Evin. Those who did convey their rage were either ignored or imprisoned.

But the culture of death continued and was encouraged in our society.

In October 1986, Grand Ayatollah Montazeri, after receiving various reports from inside the prisons, wrote to Khomeini, “Do you know the crimes that are taking place in the jails of the Islamic Republic did not even take place during the Shah’s regime? Many people have died due to torture.” Khomeini dismissed the issue.

The dadgostari (Ministry of Justice) became the bee-dadgostari (Ministry of Injustice). Mohsen Kadivar, an enlightened cleric, said it all too well; the dadgostari of the Shah’s time was much more humane than all the courts of the Islamic Regime. In these courts, the innocent and the guilty are all mixed and the sentences are carried out swiftly. No time wasted. No stay of execution in almost all cases even if the Constitution of the Islamic Republic states otherwise.

“No one may be arrested except by the order and in accordance with the procedure laid down by law. In case of arrest, charges with the reasons for accusation must, without delay, be communicated and explained to the accused in writing, and a provisional dossier must be forwarded to the competent judicial authorities within a maximum of twenty-four hours so that the preliminaries to the trial can be completed as swiftly as possible.” (Article 32, Chapter III, the Rights of the People).

Whereas Article 38 states the following, “all forms of torture for the purpose of extracting confession or acquiring information are forbidden,” from the early days of the Revolution up until now, hundreds of prisoners have undergone physical and psychological torture, often with lethal results. The 2009 elections have brought yet more torture leading to death.

The IRI brought a culture of death to Iran and legitimized it. In many ways, Iran and a majority of Iranians came to accept it. Whether guilty or innocent, death, as punishment, became the norm rather than the exception.

In the Islamic Republic, in recent times, the death sentence for political prisoners has come to be used as a scare tactic, designed to prevent others from engaging in any “subversive” activities. Often, especially in the case of political prisoners, the sentence is eventually commuted to time in prison. The Islamic regime intimidates through fear.

How do you determine that a person has engaged in activities against Iran’s national security? It is a broad allegation, leveled against each and every opponent of the regime, including journalists, political activists, and writers. It is easy and convenient. The regime in Iran does not need any justification to kill. The law of qesas,(which in Arabic means reprisal and punishment in kind) a discriminatory penal code ratified under Rafsanjani and the regime of the Velayat-e- Faqih, allows for death by execution under varied circumstances. According to Mehrangiz Kar, the Iranian human rights lawyer, “under another provision of the law [qesas], if a man kills a person and proves in court that the victim was worthy of death by religious decree’, then he walks out of the courtroom a free man.”

The recent execution of a youngster, Behnoud Shojayee, who was 17 upon his arrest and 21 when he was executed, brought rage and condemnation. However, there were those who were not too bothered with the idea of executing a “criminal.”

In fact, on Facebook, there was a discussion that one should not turn him into a martyr, for he was no angel. The circumstances behind his sentence were more than suspicious. No one knows what really happened because the truth is always hard to come by in Iran. The coroner reported that the victim’s wounds did not correspond to the blows he received in the first place. The parents of the victim were all too eager to let go of the chair that would hang Behnoud. What happened to Behnoud has happened to hundreds in Iran, and it is likely to happen again. Whether engaged in a criminal act or not, none of these souls should not have been given the death penalty, especially if they were under-aged. Article 156 of the Constitution even stipulates that suitable measures should be taken to reform criminals. This has rarely taken place. In many parts of the US, people who commit atrocious crimes are given the death sentence but usually it takes years of investigation and appeal before the sentence is carried out. According to Amnesty International, in 2007, China (470), Iran, (377) and the US (42) had the highest number of executions in the world. Iran has retained its second place until today. (Even Afghanistan has abolished capital punishment).

I remember a few years ago watching the movie “Dead Man Walking.” The parents of the victims were furious with the Catholic sister when she asked for clemency. They wanted the men who had committed the rape and the murder to get the death sentence for their heinous crime. They watched as one of them was put to death by electrocution. They were relieved.

Did it bring their daughter or son back? No. Did it console them? Maybe. But at the end it is only a partial remedy. The lives of both families were shattered forever.

A different scenario—in real life—took place in another part of the world. A white American girl went to South Africa to help and was murdered by three black Africans. The parents went back to the place where she was murdered. The three guys were put on trial but in a last minute act of courage, the parents decided that they did not want revenge; they did not want to see the death penalty pronounced on their daughter’s murderers. Instead, they hired them to work in a factory they established in her name. Was that an act of courage?

Yes, and it takes courageous people to do that.

The fact is that the IRI has implanted the culture of death. In Iran, death has become more consequential than life. The idea of martyrdom is deeply engrained in the Shi’a religion. In Shi’ism, becoming a martyr is the ultimate act of bravery. In every town and city in Iran, the first tableau you see, is “welcome to the martyr making city of …” (be shahr shahid parvar…. khosh amadid), referring to those who died in the Iran-Iraq war.

Did they sacrifice their lives for protecting Iran? Indeed. But did they have to die? Not all of them, not necessarily. Khomeini prolonged the war for political gains for as long as he could, for it allowed him to externalize Iran’s problems. The soldiers- many in their teens-carried the key to heaven and If there is a heaven, they surely deserved to go there.

One day soon, if and when a new judicial system is established in Iran, we must eradicate this culture of death, that is, if we ever want to establish a society where life has more significance than death.