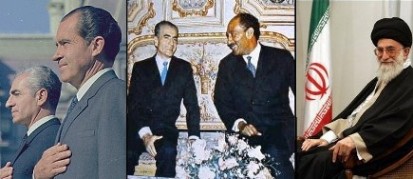

“There is no other state figure whom I could appreciate and like more.”

— Jimmy Carter, to the Shah

“We welcome you here as not only an old friend, as a progressive leader of your own people, but as a world statesman of the first rank.”

— Richard Nixon, to the Shah

Since the disputed election there’s been a lot written about parallels between the unrest we see in Iran today and what happened in the late 1970s. The combination of massive street protests, and a government that resorts to violence to put down these protests, have led many to conclude that we are witnessing a reprise of that era.

And perhaps we are, in some fashion. Certainly the current regime has suffered a grievous loss of legitimacy, and that does not bode well for its long-term survival. But I’d be surprised if this revolution proceeds with the same speed as the last. Beyond the fact that the Green Movement at present lacks a Khomeini-like figure it can rally around, my skepticism stems from the fact that Khamenei, unlike the Shah, is a cornered man whose only real option is to fight it out.

One of the reasons the 1979 revolution ended the way it did was that the Shah, when he was suffering from non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma and his regime was crumbling, had the option of leaving Iran to live in relative comfort outside the country.

This option was open to him because, over the course of his long reign, the Shah had formed friendships and bonds with ideological allies all around the world. So in 1979, when he was at risk of being drawn and quartered by angry revolutionaries in Iran, it was not surprising that one of these allies—Anwar Sadat of Egypt—offered him sanctuary. This despite the IRI’s insistence that he be extradited back to Iran to be tried and likely executed. Morocco, the Bahamas, and Mexico followed suit. And, of course, the Carter administration eventually allowed Shah to receive medical care in the United States, an act of mercy which precipitated the embassy takeover and hostage crisis. (I don’t mean to suggest that the Carter administration was rolling out the welcome mat—they weren’t. But the Shah’s ties to the US were deep and he had powerful political allies—particularly Henry Kissenger and David Rockefeller—who eventually helped persuade Carter to grant the Shah a visa.)

Fast forward to the present. Khamenei hasn’t traveled outside of Iran since becoming Supreme Leader, and rarely meets with foreign leaders who come to visit him. And no other country in the world subscribes to the notion of velayat-e faqih—so, unlike the Shah, Khamenei has no natural ideological allies. Even the Shiite Grand Ayatollahs in Iraq don’t support him.

When the opposition in Iran eventually prevails — as I believe someday they will — certainly the Bahamas won’t be offering Khamenei a get-out-of-jail-free card in the form of a house on Paradise Beach, which is what the Shah was offered.

What about Russia, then? You can bet that Putin, or whoever else is running Russia at the time, is going to be a lot more concerned about not pissing off the new government in Iran than they will be about ensuring Khamenei’s safety.

China? The communist government is officially atheist and disdains organized religion. The Chinese tolerate Khamenei and his gang because of oil. While there’s some genuine warmth between the people of China and Iran, given that they’re both ancient cultures that have been ill-treated at times by the West, there’s no personal affinity in China for Khamenei the man.

Maybe if push came to shove Khamenei could find someplace to hole up in. (The sanctuary Idi Amin received in Saudi Arabia gives hope gives hope to dictators all over the world.) But I doubt anyplace short of a virtual prison would leave Khamenei feeling secure. He’s made quite a few enemies over the years.

Which makes me think this revolution we see unfolding in slow motion isn’t going to end the way the 1979 one did, despite some superficial similarities between the two eras. The Shah had a choice of fight or flight and in the end decided leaving Iran was the more prudent option. Khamenei’s choice is more stark. He’s backed himself into an ideological corner that is crazy, dark, and without any exits. So he’ll fight as hard as he can, for as long as he can—not because he’s brave and fighting for a cause, but simply to survive.

Which is one of the reasons why this revolution, already in progress, will likely take a while.