Book Review

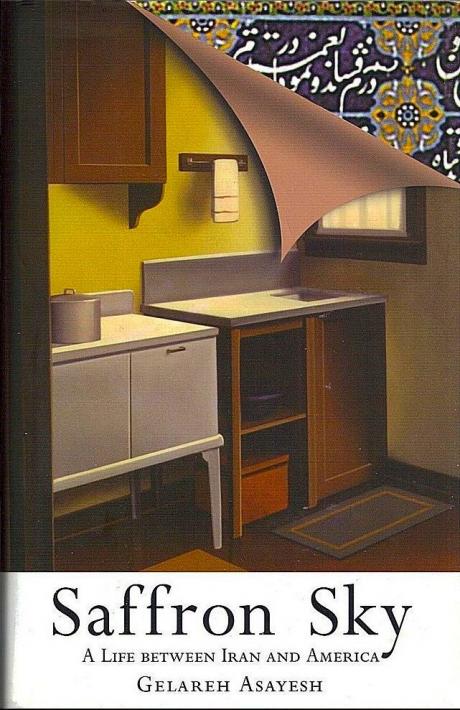

Saffron Sky: A Life between Iran and America

By Gelareh Asayesh

Boston: Beacon Press, 1999

Paperback, 222pp.

ISBN 0 8070 7210 9

Memoir of a True Daughter of Patriarchy

Saffron Sky is a well-written, shallow and unsettling tale of a search for wholeness by an upper middle-class woman who feels caught between two cultures, the idealized Iranian home of her childhood and the adopted American home of her adulthood. This is not a book about a search for identity, but rather a search for familiarity, an unending attempt to infuse an American present with an Iranian past and to create an inner peace out of the melding of the two. The book’s inconsistencies allow for a variety of readings. One reading is the immigrant’s dilemma of belonging, covering the woman’s impossible dilemma of finding herself in spite of her symbiotic ties to her family of origin. Lingering on the edge of her consciousness, this aspect of the author’s inner life remains entirely ignored.

While it is a fair account of the discontinuous life of the immigrant, Saffron Sky also speaks to the perspective of the female identity among the Iranian upper class. In fact, once we notice that, contrary to most immigrants, the author has not suffered any economic hardship, political persecution or immediate social oppression, our attention shifts from her immigrant condition to her privileged social class. Here, we find ourselves face to face with a traditional female identity, shaped by the internalized rules and restrictions, customs and traditions, and the immense weight of the family ties and classist values. Gelareh is simply too attached to her unexamined past and heritage which are inherently patriarchal, power-oriented and contemptuous of lower social classes. It is as if she does not realize that the whole package of her tribal and classist heritage, added to her binding upbringing, rejects female individuation beyond the parameters of her father’s morality. The symbiotic relationship between the members of her blood family has never experienced a “break”, or suffered a “gulf”. Instead, its seamless, pernicious presence in her unconscious, plays an obstacle to her individuation and to the making of a personal identity beyond the likes and the dislikes of her omnipresent father.

It seems that Gelareh’s feelings of guilt and inadequacy come from believing that she is not honouring her father’s decree on keeping in mind “one, the importance of going back to Iran; and two, the importance of retaining [her] identity.”(109). The anxiety of not being her father’s true daughter is projected onto the realm of the immigrant’s dilemma, making it easier to handle, and move further from her deeper truth. The result is, at the very least, confusion about the naming of her inner experiences. When Gelareh imagines the woman she might have been, that is, living all her life in Iran, and deplores her being someone else instead, someone defined by otherness because she drinks black coffee instead of brewed tea from a samovar, she is obviously confusing unfamiliarity with otherness. Otherness is an oppressive social relation, absent from the life of this “Americanized” and successful immigrant. While what is truly bothersome to her is the unfamiliarity of her present life, because her symbiotic childhood has been devoid of indications of eventual separations, losses and life’s struggles. A big part of Gelareh’s emotional turmoil is about becoming an adult, be it in America or in Iran. So, when the author wails that while working as a journalist, “there were no buffers between me and life’s harsh realities, no cocoon of familiarity and routine to shelter me, no one’s love to anchor me.”(p.120), the reader wishes to point out to her that this is what growing up is all about, that this has nothing to do with the immigrant’s anguish and affliction.

If we believe that the growth of our spiritual self, our social conscience, our understanding of our place on our life’s path, and our ability to envision our steps towards self-realization, can be achieved only through probing our past life and heritage, cultural or familial, then we feel deeply frustrated by the author’s lack of critical examination of her roots. Her father’s patriarchal deed of having kept her, for 15 years and beyond, in total darkness and ignorance about who she was and where she was, is never questioned as being in the least despotic. The historic and social roles of her feudal grandfathers in keeping women, peasants and labourers under wraps are simply not perceived. She despises the notion of Westerners’ superiority over Iranians:

“The unquestioned belief in the superiority of Americans and Europeans was an insidious, disturbing thread wound through the fabric of my childhood.”(p.80).

She remembers the contemptuous attitude of a British family who came to rent their house in Iran:

“To this day, I feel diminished by what passed between me and that family, not so much by their aloof condescension as by my eagerness to overcome it.”(p.81).

But she does not feel “diminished” by the “subtle arrogance” and “patronizing kindness” her family showed towards people of lower classes in Iran:

“Baba received deference … he was a doctor… As managing director in the Shah’s Ministry of Health, he held a position of power. The people who entered Baba’s office often clasped their hands subserviently in front, bowing repeatedly. …Homajoon also occupied a position of power and responsibility. … My sister and I grew up taking for granted our relatively elevated place in Iran’s stratified society. … Acquaintances and friends who were down on their luck always turned to my parents for help. … None of the drivers, washerwomen, maids, and laborers who came to the kitchen would ever dream of sitting down at the table with us. And, for all her kindness, Homajoon would never have asked them to. It just wasn’t done. The Western egalitarianism … seemed to be one of the few imports that had no place in our way of life.”(p.78-79)

Gelareh’s politics are emphatically conservative: the Shah “was basically pretty good although he had his faults”(P.96) and “the Islamic Republic of Iran has it’s good points.”(p.148). Her travels to Iran, from 1990 to 1999, coincide with the beginning of a feminist movement within the country that manifests itself through many clandestine feminist gatherings and study groups as well as the publication of progressive women’s magazines such as Zanan and Farzaneh that are overtly against theocracy, and many public speeches for the women’s rights in Iran by secular women activists such as Mehrangiz Kar and Shahla Lahiji. Yet, the author only contacts Zan-i Ruz, which is an organ of the Islamic Regime and talks about a single friend of hers who has embraced the world of Mullahs.

The only important part of the book is where she explains WHY she is defending the Islamic regime:

“I seek to minimize the dark side of Iran because I am afraid. If Iran is as dreadful as he says, what is there for me to come back to? After so many years of being divorced from my heritage, where will I be if I find it not worth claiming? I need to embrace Iran. Bijan needs to reject it. For I am the one who chooses to live across the sea, free to love a country that can no longer cost me. And he is the one who stays, paying the price each day for what is wrong in Iran.”(p.148).

This helps us understand why, since the beginning of the 1990’s, so many upper class Iranian women in exile, mostly educated in the field of social sciences, are defending the Islamic regime of Iran. This makes us condone even less than before such a grossly irresponsible position.

Defending the Islamic regime as a pre-requisite for “claiming” Iran, has its roots in having been on the side of the power. Those who have never been in power or do not strive for it, are able to return to Iran and claim it as their own without worry. The question of “Whose Iran Is This?” comes from the undemocratic minds of the upper class Iranians. Iran belongs to all citizens of the land and the need to defend its brutal regimes has rarely crossed the mind of its people.

Saffron Sky does not bring the Iranian reader to a new understanding of the life between two cultures. Instead, it is invaluable in understanding the “emotional agenda” of the Iranian upper middle-class in exile who remain, along whatever journey, true offspring of its patriarchal past. It is invaluable in understanding the unreliability of a social class that has very close roots in feudalism, flirts with communism, is alternately for and against the Shah, produces Ayatollahs, pretends to be for feminism, feels inferior to Westerners and then challenges them for their arrogance, and finally reinterprets all the social events and all the ideologies under the Sun.

Note:

This book review was published, in 2000, on my now-defunct website.