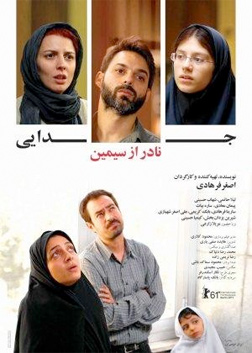

Two questions frame the film Nader and Simin: A Separation, the first in the opening scene of the movie and the other in the final scene. “What conditions?” the judge asks Simin when she says she wants to divorce Nader and leave the country because she prefers her daughter not to grow up under “these conditions.” Simin leaves the judge’s question unanswered, but from there the drama moves relentlessly towards that final question, which the judge puts to Termeh, the couples’ daughter: “do you want to stay with your father or with your mother?” By then each of us has a clear answer to the first question.

In the marvelously efficient opening scene dialog we quickly discover that the “condition” Simin is talking about has nothing to do with Nader being a bad husband. He’s handsome, liberal, educated, reasonably well off, considerate, and devoted to his wife and daughter. So why is this woman breaking up her family on a whim to take her child and live abroad, we wonder disapprovingly. Perhaps she’s tired of helping care for Nader’s father who has Alzheimer’s. Hardly evidence of good character. But as the story slowly raises the workout level for our sense of morals to more and more arduous settings, this simple take on who Simin is appears petty. Director Asghar Farhadi isn’t judging right from wrong; he’s exploring the very nature of morality.

Take Razieh for example, the woman Nader hires to tend to his father after Simin leaves to stay with her mother. The pious Razieh is an innocent to the point of having no autonomous sense of right and wrong. Why else would she call the Islamic hotline on the phone to find out if it’s appropriate to clean a disabled old man who has soiled himself? Though Razieh inclines to compassion, when it comes to action she abdicates her conscience to religion. This leads to some admirably moral behavior on her part, but does the credit go to her or to Islam?

Razieh’s husband, Hodjat, doesn’t even have piety to keep him decent. His is a survivor’s sense of ethics, as in none whatsoever. Yet he has a well-developed appreciation for justice when it comes to what he is owed. In fact he bullies and blackmails in the name of justice. In a fit of anger at seeing his old father neglected by Razieh, Nader had pushed her, possibly causing the pregnant woman to miscarry. Hodjat will not rest until he is properly compensated for his unborn child’s death.

Nader shows more free will than Hodjat or Razieh. His humanity is not overwhelmed by base survival instinct, and he is not religious. Yet he has his own prosthetic that he uses for a real conscience: a strong sense of duty to his father. He and Simin had planned for years to leave Iran with their daughter, but when their paper work is finally ready Nader decides he has to stay to take care of his father. Was he leading Simin on all these years? Why doesn’t he feel the same sense of duty to his wife and take responsibility for his change of heart by allowing Simin to take their daughter abroad with her?

This situation puts the 11-year-old Termeh in a terrible bind. With her parents’ separation inevitable, ultimately she will have to decide which one she will stay with. Ironically, the tragedy of Razieh’s miscarriage and the court struggle that follows has given Termeh an opportunity to watch the mettle of each of her parents put to the test. If Separation had a narrator, it would most likely be Termeh.

Termeh’s father is a man who struggles to the point of delusion to clear his sense of guilt and prove himself innocent to the world. He refuses to think of himself as someone who would do wrong, which is easy to do because there’s always room to flip a wrong to a right by upping the level of complexity. In this reckless quest to rescue his sense of moral self-perfection he puts his daughter in the awful position of deciding whether or not to lie in a court of law.

Terhmeh’s mother, on the other hand, feels guilt as a responsibility, not naively as the opposite of innocence. She takes it as a fact of life that sometimes in the normal process of being ourselves we cause others harm. She accepts this about her husband without a moral struggle because, to her, doing the right thing by others is all about working hard to create acceptable compromises. Lelia Hatami’s deadpan style of acting works very well for Simin’s practical take on ethics.

This character analysis may give the impression that Separation is an intellectual movie. It can be, but at the same time it is as sentimental as any signature Iranian film. There are heart-wrenching performances particularly by Sareh Bayat (Razieh) and Sarina Farhadi (Termeh), and there are engaging mysteries, clues and plot twists leading to that final courtroom scene where the judge asks Termeh to decide between her parents. Farhadi does not let us know Terhmeh’s decision because he does not wish to editorialize on the issues he has raised. We can tell because Separation has no background music to tell us how to feel. After all, if God played music for us as we went through life our moral dance would be a lot simpler.