The first months of 2012 have been dominated by analysis and speculation over a possible attack on Iran over its nuclear plans. In this delicate situation, understanding the calculations of the authorities in Iran is clearly vital. So what is happening in Iran, and how is the combination of internal political developments and external pressures on the government in Tehran – such as tripling sacntions and the threat of war – being played out?

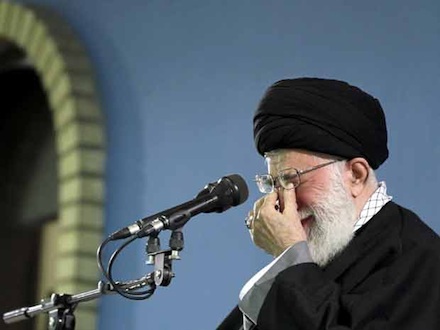

A place to start in answering these questions is the comment by Iran’s supreme leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei on 8 March 2012 which responded favourably to President Barack Obama’s statement that he was not considering war with Iran. Khamenei, speaking to members of the Assembly of Experts (one of Iran’s leading constitutional bodies), said: “This talk is good talk, and is indicative that [Obama] is outside of the illusion. But the president of America continued to say that we want to bring the Iranian people to their knees with the sanctions. This part of his talk is indicative that the illusion continues in this respect… Continuing this illusion will hurt American officials and their calculations will fail.”

The comment had been preceded by the parliamentary elections in Iran on 2 March which gave a solid majority to the circle around the supreme leader. This outcome raises the question of how current power-struggles within the Iranian elite are likely to affect Iran’s foreign-policy course, particularly over its ambitious and costly nuclear programme.

The power-struggle

Ayatollah Khamenei is ultimately in charge of Iran’s major foreign-policy decisions, including the nuclear programme. Yet internal factional conflicts, broadly between conservatives and reformists (often perceived as the two wings of Iran’s political system – with the supreme leader the central figure in the former camp) can strongly affect the pace of decision-making. Until recently, the balancing factor of inter-party struggles provided Khamenei with political cover. But Khamenei, with his supporting base in major political institutions, has gradually managed – both in the turbulent aftermath of the presidential election in 2009, and again in the 2012 parliamentary elections – to remove reformist forces from Iran’s political scene.

Now, conservatives rule almost all major civil and military institutions and the supreme leader has established a commanding role in managing the country’s major policies. Thus, any damaging rift between pro-leader conservatives would now put Khamenei in the spotlight, damage his authority, and make him vulnerable to blame for any wrongdoing by his supporters.

Khamenei’s awareness of this, and his desire to deflect responsibility for failures and unpopular policies, mean that he tries consistently to present all decision-making (even when carried out with his direct orders or in consultation with him) as a product of collective thinking by his subordinates.

Khamenei enjoys the complete support of the leadership of the Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and is ultimately in charge of all the country’s powerful military and intelligence organisations. He has avoided implementing policies that could accelerate the existing rift among the conservatives. This will have an impact on the actions of the newly elected parliament and on the ongoing crackdown on Iran’s internal critics and dissidents.

This crackdown has seen many journalists, filmmakers, bloggers, civil-society activists, and workers who attempt to demand their labour rights face the state’s iron fist, and are rotinelyroutinely charged with offenses such as “acting against national security” or “presenting a dark portrayal of the state.” In addition most reformist leaders, including the opposition presidential candidates Mir-Hossein Moussavi and Mehdi Karroubi, are either in prison or under house-arrest. Many prominent reformists, such as former president Seyyed Mohammad Khatami, face serious limitations on their political activities. There are restrictions on journalists’ reporting of their predicament or news related to them.

The reformists played no part in Iran’s parliamentary elections. In part as a result, Khamenei has been able to shape the most homogenous ruling group in the history of the Islamic Republic of Iran. Yet a side-effect of this outcome is that failures and shortcomings in the country’s policies can no longer be blamed on reformists, who were in charge for eight years before Mahmoud Ahmadinejad became president in June 2005, and not even on those conservatives who have distanced themselves with the leader.

In this sense, Iran’s supreme leader is now in a more vulnerable position than it would appear. Even in the new parliament, again comprised of a conservative majority loyal to Khamenei and critical of Ahmadinejad, support for him is not absolutely assured. Two major conservative groups won more than half of the seats – the Islamic Revolution Stability Front and the United Principalists Front – but the true affiliations of more than 100 new MP’s are unclear. Some analysts believe that a large proportion of these could be backed by Iran’s vice-president Esfandiar Rahim Mashaei, who is scorned by supporters of the supreme leader. In addition, a small group of the newly elected – which includes Ali Motahari and Ahmad Tavakoli – are staunch critics of the government. But since the nominees (under velayat-e faqih, the rule of the jurist), it is almost impossible to find out whose vow of loyalty is real and authentic until they start their work in the parliament.

The political timetable

There are fifteen months to go before Iran’s next presidential election in June 2013. Until then a powerful, critical parliament will be able to limit the activities of Mahmoud Ahmadinejad – perhaps even impeach him after an investigation into his financial affairs. Just days after the parliamentary elections, the president was questioned before the current MPs. In the style of his seven years in office, his provocative performance was matched by angry reactions from some MPs. Some of them now talk of impeaching Ahmadinejad for his incompetent performance, something that in principle will be easier to pursue in the new parliament.

For his part, Ayatollah Khamenei will seek to prevent the incumbent president from using funds and influence over the next two years to choose a potential successor from among his own friends and affiliates. Khamenei will want to promote his own favourite, possibly Gholamali Haddad Adel, the current deputy speaker of parliament and a close relative of the supreme leader.

The embattled Ahmadinejad thus faces a struggle to survive even until the end of his term in office. But as head government he still holds two powerful cards: Iran’s booming oil revenues (partly as a result of the threats of attack) and access to the intelligence ministry. He has insinuated several times that he has information potentially damaging to the supreme-leader’s supporters, which he could reveal if necessary. So Ahmadinejad could retaliate in kind if (for example) he is accused of corruption or if he or or his inner circle are put under extreme pressure.

The probability of continued tension between president and supreme leader – where (for example) the president seeks to obstruct any major political decisions taken by the supreme leader or groups under his oversight, especially in areas such as Iran’s nuclear programme or its foreign policy – is a recipe for paralysis until the end of Ahmadinejad’s term. The implication is that even if the west opens the way to negotiations over Iran’s nuclear programme, the chances of a successful result that meets the west’s concerns are minimal.

The only way out of a political standoff of this kind could be a sweeping crisis in which military groups, particularly the IRGC, practically take control over the country and marginalise the president. That scenario may be why some groups within the Iranian leadership and the IRGC might even welcome any short-lived military attack as a pretext to cement their power inside Iran’s ruling elite.

Iran, after all, has long experience of internal forces using foreign policy as a tactic to gain more political power. The case of a military attack by the US or Israel (or both) on Iran’s nuclear or military facilities – or even accelerated verbal threats to this effect – would be convenient for those seeking to impose a state of emergency in the country that enabled the IRGC, under the oversight of the supreme leader, to replace Iran’s civilian politicians and take control of all state affairs.

Most signals of war from the west suggest that any military attack on Iran would be limited, intended to disable Iran’s nuclear facilities and postpone the country’s acquisition of nuclear weapons. Whether any assault succeeded in this, Iran’s more extreme factions could use it to concentrate power in their hands, to suppress dissidents even further, and to reach out to public opinion in the region. It is at least certain that they would be strengthened by an attack.

There are very few options that could today lead to a sudden change in Iran’s foreign policy. One is for Ahmadinejad to present the supreme leader with a fait accompli regarding important decisions, such as over Iran’s nuclear activities (in 2009 the president acted in this way by dismissing the intelligence minister that Khamenei had handpicked). Another is for Khamenei to reduce the president’s authority and delegate fundamental decisions to committees under his control.

This rooted internal tension means that substantial changes in the balance of political forces are unlikely before the presidential election of 2013. But the pattern could alter if Iran’s leadership becomes convinced that intensified economic sanctions or military action could lead to irreparable damage to the Islamic Republic’s political life.

Iranian leaders know that extreme conditions could challenge the state’s rule at its very heart. The defence of the state is the red line that Ayatollah Khomeini and now Ayatollah Khamenei have observed since the Islamic Republic’s inception in 1979. In this sense the west’s policies towards Iran in the coming months could be more influential over Iran’s foreign policy than internal developments.

First published in opendemocracy.net.

AUTHOR

Omid Memarian is a journalist who writes for the IPS (Inter Press Service) news agency and the Daily Beast, and whose work has been published in the New York Times, the Los Angeles Times, the Wall Street Journal, and the San Francisco Chronicle.