I saw ‘Footnote’ with a dear friend of mine. Neither of us is Jewish, or speaks Hebrew. Nor has either of us seen an Israeli movie before. While still young at heart, neither of us has been exempt from the tyranny of time or biology. So, in some respects at least, both of us have been where we could have, and done what we should have, to develop immunity against the ongoing assault of the profane politics. Our interest in seeing this film had more to do with the fact that (a), it did compete against ‘A Separation’ in the foreign language category of the 2012 Academy Awards, and (b), from what we had read about its plot here and there, it had a theme familiar to both of us. As we both noticed while watching the movie, Cedar as a film author – screenplay writer and director – has more in common with Asghar Farahadi than we expected. However, ‘A Separation’ and ‘Footnote’ belong to different genres.

‘Footnote’’s protagonist, Eliezer Shkolnik is a meticulous purist yet underachieved philologist of implacable integrity. He has dedicated four decades of his life to piecing together the authoritative version of a body of religious knowledge and tradition, just to be perished by the unearthing of the original text in a remote monastery. He despises his colleagues for failing to validate his contribution to the esoteric field and to afford him the recognition he believes he deserves. In an interview, following the unexpected announcement of his winning the prize he has always coveted – the most prestigious national award for scholarship – he goes as far as denigrating his own son, an accomplished author and popular philologist, as a frivolous researcher. He accuses him of being a gregarious celebrity feeding on public acclaim and accolades. The son, Uriel however, learns that in fact he is the intended awardee, and their shared surname is responsible for a clerical blunder. In what is seen as the manifestation of genuine filial love, he insists that his father remain the award recipient. However, his attempt at resurrecting his father’s failed career appears to have cost him his own grand aspirations and future.

In the opening scene, Uriel is heard giving the acceptance speech after receiving an honor of distinction, while the camera is zoomed on the face of his father who is seated in the audience. Giving credit to his father’s influence on his own career, Uriel recalls a childhood anecdote in which, in response to a question about his father’s occupation in a form sent home by his school, Eliezer had refused to characterize himself as a university professor or a philologist, and had insisted, to his son’s disappointment, that he be simply identified as a teacher. During this gratifying speech, one expects to see a gleeful father proud of his son’s success. Instead of admiration, the father’s disdainful face reveals a sense of betrayal – as a matter of principle, not to be mistaken with jealousy. To him, the style had been honored not the substance.

Soon enough though, the initial and comfortingly idealistic impression – a man of high standards and his gratuitous son – is turned on its head by Cedar’s wit. The narrative metamorphoses into an apparently ignoble rivalry between a father and son conjoined by familial loyalty, but determined to win each other’s – and public’s – respect. The facile plot lends itself as the veneer for an equally ignoble competition – in a parallel universe – between two sets of intellectual values, two schools of thoughts, one traditional, altruistic and pedantic, and the other contemporary, faddish and populist. The intrigue climaxes when Eliezer’s zeal is matched not by Uriel’s but by that of another old-timer, the chairman of the nominating committee, who in a meeting convened to search for a plausible way to retract the award from the unintended recipient, refuses to accept the significance of Eliezer’s contribution to the field. The chairman states in a categorical – and ostensibly principled – manner that Eliezer’s work merits no more than a mere acknowledgement he received some years back in a footnote in an eight-volume encyclopedia written by his legendry mentor. Fearing his father’s catastrophic reaction to the news, Uriel unabashedly accuses the chairman of bearing grudges against his father and physically attacks him. Academic demeanor gives way to tribal instinct.

At the end, all angels fall from grace: truthiness outflanks the truth. The chairman concedes to Uriel’s demand, provided the son drafts the citation letter enumerating the father’s scholarly achievements and the reasons for the committee’s decision; a precarious challenge Uriel unenthusiastically consents to. “There are things more important than the truth,” he pleads. The letter is written and delivered. It does not take much effort by the philologist father to recognize the letter’s author. It is left to the viewer however, to decide whether Eliezer regards the letter as a belated affirmation – by his son, as well as the committee – of his lifelong undertaking, or realizes his son’s machination. He is seen embracing the missive, nonetheless. It remains unclear whether it is his vanity and lust for recognition that have prevailed over his earlier inhibitions and humility to turn him into a willing participant in the absurd game of publicity and political stunt that follows, or this is just a mischievous act of revenge on his part – It is not always easy to distinguish a smile from a smirk. The complicit yet disgruntled son watches the charade.

In ‘Footnote’, the semi lit, crammed and claustrophobic closets filled with books, bookworms and bureaucrats become metaphors for closed mindedness in a purportedly academic setting. As though no one has ever discerned the meaning of ‘Let there be light,’ cantankerous characters mix the damage control with haranguing over the merits of a colleague’s lifelong work, while blurring the border between peer review and prejudice. Not only Cedar leaves no character unscathed, he questions the institution of academic meritocracy as a whole. He brilliantly uses the security wristbands as measures of social acceptance and prominence. His omnipresent checkpoints and body scanners separate not only the authorized from undesirable, but also the established from the footnote.

Despite significant overlaps between ‘A Separation’ and ‘Footnote’ in delving into human nature – revealing strengths, weaknesses, and ethnical dilemmas – in one aspect the two movies part ways: the role played by female characters. In contrast to Farhadi’s, Cedar’s women are passive and traditional housewives inhabiting a male-centric world, with not much of an impact on the turmoil surrounding men’s personal and professional lives. Eliezer’s wife, a dignified old lady seemingly content with her family and social status, willingly lends her compassionate shoulders to every family member to cry on – a patience stone. Uriel’s wife is a vulnerable and insecure woman who witlessly attributes her husband’s marital fidelity, and kindness, to his cowardice! Their apparent character differences – ingrained or age-related – are immaterial to the film’s plot. One hundred years after three strong-willed daughters shook, shattered and reshaped their father’s religious beliefs and traditional life style – in Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye and his Daughters – Cedar’s women appear as casualties of prearranged marriages.

We saw this film on a late afternoon in a small theater with fewer than a dozen other viewers, mostly elderly. When the film ended, the theater remained dark for quite some time after all the credits were shown. There was no one to turn the lights on, not even the projectionist. We left under the dim emergency lights. I wondered if it had to do with the day coinciding with Holy Saturday. Or maybe, the theater ushers did not want to acknowledge that we – the few – witnessed the fall.

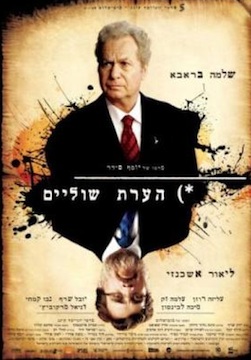

Footnote

Joseph Cedar won the screenwriting award at Cannes 2011 for ‘Footnote.’