PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

‘To Feast, or Not to Feast?’

Saturday, 3 May 2003

The biggest story for the past couple of days has been a speech by President Karzai who said that being a member of the Taliban cannot in itself be considered a crime. He had earlier asked the government of Pakistan to hand over some named Taliban officials so they could be tried in Afghanistan.

In his more recent speech, he named a few other Taliban officials as people who had tried to serve the country. This has led to protests from the Mojahedin factions who fought the Taliban between 1996 and 2001. While Mr Karzai seems to be trying to split the ranks of the Taliban, he may also split the ranks of his supporters.

Over the past couple of months, with the weather improving, there have been many more clashes around the country, especially along the southern and eastern borders with Pakistan. The anti-government forces say they have also sent their men into Kabul and other big cities. I have already told of you some explosions around Kabul a few weeks ago.

Today, as I was walking back from the television station to our office, I saw a mini-bus with blacked out windows overtake the traffic and make a sharp turn at an intersection. A few moments later, a hand came out of the left-hand, front window – it was one of the right-hand drive vehicles that have been imported from Pakistan. The hand was holding a pistol and fired a few shots in the air and the vehicle disappeared along the road. Oddly enough, I seemed to be the only person who noticed this. Maybe such shooting occurs on a regular basis and people are used to it. This comes shortly after assurances about increasing security in Afghanistan, given by our old acquaintance, Donald Rumsfeld, who flew in here a short while ago.

At Afghanistan Television, I ran two courses, in Persian and English, which were very enjoyable. I also arranged a meeting to discuss the women’s programme with the whole production team, something that does not happen on a regular basis. The staff are very open and receptive, once they are convinced that you are there to help, not to instruct, order, or do any other stupid thing. To find my way to the two meetings I walked through more of the station and saw so much decay, destruction and disrepair that I became convinced it is a miracle that anything gets made and broadcast at all.

The packed day meant that I had no time to go to my favourite restaurant, Sahel-e Sabz, but had to make do with some almonds – a gift from one of the colleagues – and an apple. Our farming expert, Ehsan, told me the almonds had been grown from an American seed which made them bigger than the Afghan variety, but less tasty. The more you make of something, he said, the less taste it will have. Ehsan is such a nice soul, so well informed, so skillful, and so kind and gentle. Later, looking at the newspaper, he made a very sound editorial comment about the presentation of one of the news items. I hope he will be able to move on and do much more varied things – like all our other colleagues who are so talented, but have had limited opportunities so far.

The past two days have been rather cool, this afternoon feeling like autumn. Two nights ago, there was even some rain and a hurricane that knocked down a few trees. In proportion to the total number of trees, probably more damage was done by the Kabul hurricane that by the one in London all those years ago. The hurricane apparently also knocked down a main power pylon and left much of our part of Kabul, including the TV station, without electricity.

I had first gone to the TV station to see the women’s programme being recorded, but there was no recording because of the power cut. Power was still out when I went back in the afternoon for my classes. On the plus side, we held one of the classes in a nice ground floor office that was much friendlier than the lecture hall we have used so far.

For the other class, we went to a deputy director general’s office on the fourth floor with a beautiful view of Kabul, the Radio and Television Hill and the massive structure built by the East Germans many years ago to house a huge radio and television centre, a model of which, with Russian inscriptions, was on a table in a corner of the Deputy DG’s office. It will be some time before anything on that scale can be built in Afghanistan.

Walking back to the office at the end of the day – this time without any gunfire – I came across a group of kids who tried, and failed, to sell me a newspaper I had already bought. One of them then asked for ten Afghanis for himself and his friend. I objected and said they should not beg, but continue selling papers, on which note the little boy showed me a magazine I had not bought and did not really want, but had to buy since he was following my words. He charged me 50 Afghanis, a lot more than the cover price. So my advice worked, at least for these kids who sold something to me.

Sunday, 4 May 2003

Today, once again no guns were fired on the street – at least not where I was – but I saw pictures of rifles, RPGs, tanks and fighter planes woven onto carpets hanging form shop windows on Flower Street, or Koucheh Golforoushi. We’d gone to Flower Street to buy some flowers and cookies for a colleague whose 19th birthday it was today. A very smart guy, he started work as an interpreter but has the capacity to do a lot more, given the right opportunities for learning and training, both of which he grabs wherever they can be found.

We also wanted to gift-wrap the present we had got for our colleague. The wrapping was done very tastefully at a florist where we also got a beautiful bouquet for about 4 pounds. Two kilos of cookies came up to just over 1 pound. Before the gift finding trip, some fifteen of us had been invited to our colleague’s birthday lunch at a restaurant called Marco Polo, serving nothing but Afghan dishes. The restaurant has one big hall and a smaller hall with tables and chairs, and a third hall with carpets and big makhadah, or cushions, where you sit down on the floor and eat. It would be an ideal place for a heavy meal of various kebabs and rice, to be followed by a deep sleep right by the side of the sofreh.

In addition to shops selling carpets, jewellery, and antiques, Flower Street is also host to a bakery with croissants and baguettes, and a shop called Chelsea, which is frequented by many internationals. I have not been there, thanks to Agha Sarwar’s catering skills, but I am told that Chelsea’s main feature is that it charges higher prices than any other shop. Given what the Afghans have been through, I would say as long as people are willing to go there, the excess charges should be the shop-keeper’s noosh-e jan.

Driving down the street, a colleague pointed to some foreign names painted on shop windows and said this showed the Afghan shopkeepers’ keen sense of the market and their ability to send signals to please the customers. Under the Taliban’s strict Islamic rule, with many Arabs based in Kabul, the shopkeepers would add the Arabic prefix al to their businesses names. Nowadays, the al-whatever has given way to western or western-sounding names.

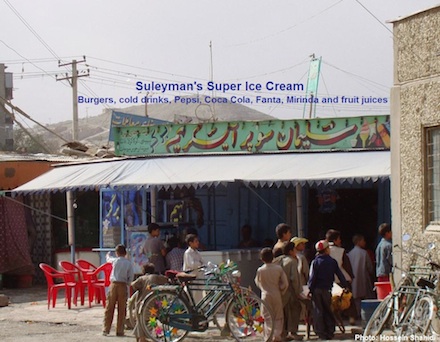

Not everybody is pleased. The writer of an opinion piece in the newspaper, Arman-e Melli (National Ideal), this week expressed fury at having seen the sign ‘Burger House’ on a fast foot joint near his office. Other offending signs included the English word ‘crockery’ for a shop lending, well, crockery, for parties and such; and ‘bakery’ for a shop selling cookies. The writer was also furious with ice cream shops calling themselves not sellers of shir-yakh (frozen milk), the Dari name for the substance, but ‘Super Ice Cream’, or something like that.

What’s worse, the writer revealed, at least for someone like me who’s never been to such joints, that the ‘Super Ice’ shops play videos as an added attraction. Young people would go into the shop, order an ice cream and prolong the eating experience as much as possible –difficult in hot weather – to have the right to sit in the joint and watch videos. As soon as the shir-yakh is finished, the staff would start pushing them out, unless they order more ice cream. This, the writer said, was wrong on two counts: forcing the customers to buy more than they would really want, making them vulnerable to all sorts of diseases, ‘including SARS’; and showing videos of suspect moral quality which could corrupt their minds.

In the morning, we had a very productive and heart-warming meeting with the producers of Afghan TV’s Woman and Society programme about which I have already written. Having seen their working conditions, I said once again that it was a miracle that they were putting out anything at all, but we needed to discuss the latest episode that we had all seen to find out if it needed and could be improved – initially with the same, limited available resources. In spite of some scepticism, mostly from those closely involved with the programme, the brief, nameless questionnaires that I asked them to fill right there and then produced a list of about ten things that could easily be changed and result in a more engaging show.

I must admit that at the beginning of the meeting there was a moment when I felt this was going nowhere, and that I would have to announce the end of this attempt, with great sadness. At the end of the 90 minute discussion, probably unheard of in the team’s experience, we had agreed to meet again, on Sunday, to review today’s recommendations and to go through the next show’s script together to see what could be done differently.

It is still too early to say anything about the outcome of these efforts: they really, really, really are very hard pressed and I would not blame them – especially the women, each of whom has several children – for not having pushed themselves much more. But I am very optimistic that in spite of the old cameras, edit suites with no chairs, and few vehicles to take them around – not to mention the long power cuts – they could achieve a lot more through greater imagination and cooperation, and out of a deep sense of commitment to the Afghan public, most of whom are much worse off than any television producer.

Monday, 5 May 2003

I’ve just come back from a reception at a house on the other side of our block, held by another UN organisation to entertain about a dozen of their staff from across the region, including Iran, who’re here for a workshop. It was an interesting couple of hours, in an environment even more surrealistic than our own guest-house – with a bigger, well-maintained garden and a swimming pool. Music was being played from an MP3, James Bond posters from a previous party were on the walls, and a feast on the tables. It could have been anywhere in the West.

It’s hard not to compare these images with those from films about colonial India or Africa. The main difference is that the UN presence here is not directly military, although it has the backing of NATO from a distance. How this plays out in the minds of the Afghans is difficult to tell. At the reception, there were about ten Afghans, most of whom did not appear to belong, or to feel that they belonged, there. They left before everybody else, and without the normal pleasantries of bidding farewell and being followed, at least a couple of steps, by the hosts.

The separation between the Afghans and the Westerners, with whom the few of us Iranians were associating more closely, was uncomfortable enough. But then an Iranian guest with whom I had shaken hands and exchanged greetings earlier on came over to me and apologized for having taken me for an Afghan. He said this very sweetly, perhaps just as he would have said it if he had taken me for an Italian, or an Indian. But the Afghan context in which we are living made the remark sound rather rough.

The workshop is about information dissemination to Afghan refugees, especially in the region (Pakistan, Iran, Central Asia and India), so they can decide whether or not they want to come back. One of the most striking points made at the workshop was that parts of south-east Afghanistan have turned to desert over the past twenty odd years and cannot accommodate the refugees who originated from those areas. This confirmed what I had learned from a UN environmental report a few weeks earlier [Chapter 2: Land of investment Opportunities, entry for 17 February 2003].

I was asked to speak at the meeting, describing what UNIFEM was doing, especially our team’s data collection on women in the media, the results of which are quite impressive. We now have a collection of more than twenty newspapers written by women, for women, and a list of fifty women whose names are mentioned in the newspapers as contributors. I myself could not have imagined this when we started looking around Kabul for women’s newspapers.

Afghan papers regularly carry horrifying stories of young girls being forced into marriage, sometimes with people they have never met, sometimes to a man to whom a girl was ‘engaged’ when she was still in her mother’s womb, and the tragic consequences of such arrangements – including women committing suicide. Marriage could be forced on a young girl because her family owe money to a man or his family, as a ‘favour’ to the man’s family, or because someone in the girl’s family –almost always a man –killed someone in the ‘bride’s’ family. Such ‘customs’ are not unique to Afghanistan, but are also part of tribal life in other parts of the world, including Iran.

Today, I read the first story I’ve seen about a man having been forced into marriage! In a letter to a paper, the man says the marriage was imposed on him by his father, and his wife is ‘rude, violent and ugly. She never listens to anything I say. I have even beaten her up several times, but it has not had any effect.’ Now compare this with numerous accounts of women complaining of being beaten up by their husbands – obviously these are the cases when the beating up has had some ‘effect’. One could make a number of jokes about this, but the whole thing is very sad.

Another sad, and ridiculous, image was created by a BBC interview with the British officer who has been appointed as deputy to the American ‘governor’ of Iraq, the former American general and arms merchant, Jay Garner. Speaking about electricity shortages in Baghdad because of the destruction of the power plants by the Americans and the British, the British officer said there were still cuts, but the situation was improving and, anyway, the conditions in Iraq were much better now than they had been three months ago because the Iraqis were now free to speak their mind. The website, Iraq Body Count, says between 2,197 and 2,670 civilians were killed in the attacks on Iraq. These people have failed to use their opportunity to be free.

Tuesday, 6 May 2003

I need to start with a major correction to what I said yesterday about the UN presence, not just because I myself work in the UN, but because I have thought a lot more about what it has tried to do here and elsewhere in the world, and about the UN staff I have met here. It is true that the NATO military presence has contained the faction fighting and allowed the UN operations to continue. It is also true that as an organization, the UN is made up of its member states, at its highest levels controlled by the strongest among them.

It is also true that like all organisations there are people in it who would not care for much more than their own positions and salaries and benefits. But on the ground, it is also made up of people who have ideals and human values and do their best to help others. In many cases the human misery that some UN organisastions have to cope with is so immense that I find it hard to believe that any cynical person could stay in touch with them for any length of time without changing their attitude.

At the reception last night and the workshops yesterday and today, there were people from Afghanistan, Iran, Uzbekistan, Pakistan, Italy, Switzerland, Britain, Colombia, and United States brought together by the real need to do something for some 6 million people driven out of their homes in Afghanistan. The Afghan colleagues are, of course, closest to the trauma and most deeply affected by it. But there are also clear expressions of understanding, sympathy and even pain in the voices of people from other parts of the world who have come to Afghanistan as UN specialists.

The question is: will such people be willing to come to Afghanistan to live in tents or bombed out houses, like the Afghan refugees themselves? If the answer is ‘No’, does it mean these people are selfish, or that their skills do not have any real value? If the answer is ‘Yes’, would it be a good idea to let them do that? How much would a technical or medical expert, an economist, an administrator, or even a mere journalist, be able to do to help others while living in circumstances very much like theirs?

And if they were able to do something, would it be much more than charity – an act of giving that is meant to relieve the conscience of the giver, rather than provide long-term, sustainable support for the recipient? Also, since the UN staff do live in expensive accommodation, in fact they are also putting some of their income back into the local economy.

Just as I had come up with these ‘balancing’ thoughts, I heard a report on the BBC Persian service from Kabul, about a demonstration against the government by some fifty Afghans, led by a former university professor. The protestors were asking why a government minister’s monthly hospitality bill should be about 1,200 dollars, when a civil servant earns about 40 dollars a month. The reporter also said that there was increasing unhappiness among Afghans about foreigners living here on high salaries and raising the rents and property prices.

You may also remember what I wrote a few weeks ago about some Afghans not accepting that all those who have come from abroad, including the Afghans returning from the West, do indeed have skills that would justify their salaries. Such critics would say that those who have come back were no more than cat- or dog-washers in the West, rather than first rate specialists of any sort. So, it seems that what presents itself to me as a question, appears in the minds of other people as a matter that has been resolved, and not in favour of the expatriates or the local, returning elite.

***