PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

Phones From Heaven

Tuesday, 24 June 2003

The women’s business exhibition and conference went extremely well. The business side ended with a discussion of problems and suggested solutions – ranging from improved packaging for dried fruits to disarmament of Afghan militias and the deployment of the international military force across the country. There was then a half hour cultural show, with live music – some Iranian and some Afghan – as the background for a presentation of traditional clothes from around Afghanistan. Each time, a woman from the area would say a few words about her province.

Some read brief statements about peace and prosperity; others spoke of women’s bravery or woman being, as one lady put it, ‘the most perfect creature’. One woman form Mazar-e-Sharif, in the land of the 9th century woman poet, Rabe’ah Balkhi, and the 13th century philosopher-poet, Jalaleddin Balkhi, aka Rumi, read a poem which said:

With the palms of my hands, I shall make you a bed

With my eyes I shall make pillows so you can rest your head

And if the road to Mazar you should ever tread

I shall cover the earth with a carpet, coloured with my blood, red

Our efforts to get the media interested in women’s activities have finally paid off. Yesterday’s opening of the conference was reported on Kabul TV, but only because we had arranged for the crew of the Woman and Society programme to be driven from their office to the site of the conference, and had made sure that the national news agency would also cover the event. The TV news story contained lots of shots of the audience and the speakers, including Parvin, who was also named in the report.

Today, we had two TV crews covering the conference. One had come from a cultural programme to cover the exhibition of women’s products, although they had missed the three days of the big show and now could only film the much smaller one in a room near the conference hall. Once they were with us, I persuaded them to look at the conference as well. Inside the hall, they saw and were captivated by the selected items on display, so much so that they spent more than half an hour filming almost all of them, with the relevant signs indicating the provinces from which the products had come.

They then went to film the small exhibition which included a stall with metallic and beaded ornaments as well as metal urns and vases and a tea pot with seven spouts. On inspection, it became apparent that only one spout actually led to the pot and the others were ornamental. The gentleman who was tending the stall – I suppose because any women associated with those products were at the conference – said he thought the pot was made in China. When I showed him the Persian inscription at the bottom of the pot, he said it must have come from Herat. He also believed it was made by a man, as were several other objects in that particular stall at a women’s products exhibition. Considering that lots of things made by women have been marketed by men, maybe it’s only fair that women should now be selling their menfolks’ handicrafts as their own.

The other TV crew were our old friends form Woman and Society. They first came over in the morning, in the car that we had sent them, but without a camera. I asked them to look around hall to get a feel of the women’s discussions and then go back to the TV station to get a camera. While they were busy watching and listening, I rang the station and asked for a camera, which they said they would make available.

Not only did the camera turn up, but also three more people from the programme, including the head of department. They too spent a good deal of time shooting and interviewing, which they said would be used in a 20 minute segment in next week’s programme. There were also many radio and news agency journalists around, so women’s economic activities are going to be a big story for a few days at least.

To celebrate, Parvin invited the North American businesswomen and some of us who had worked closely with the conference to the Karwansarai restaurant, about which I have written before. This is a delightful place run by Seema Ghani, an Afghan woman who came back from Britain about a year ago. Since opening last December, she has turned a large plot of land with two old and beautiful but damaged buildings into a hotel and restaurant complex with a gym and an internet hut – with a roof made of straw mats.

Three months ago when I went there first the ground was vacant except for dumps of earth and bricks. Now, there is a beautiful lawn with a pond filled with water pouring down a small mound of rocks. Low tables were placed on rugs, around them mattresses and large cushions. The setting made our North American guests gasp with amazement and delight.

By sundown, as several muezzins began their call to prayers – in voices much better than their colleague in our neighbourhood – lines of light around the lawn were turned on. Later in the evening it was possible to lie back and watch the sky full of stars. What was most amazing was that at a time when most parts of Kabul can be uncomfortably hot even at night, you could actually shiver with cold in Karwansarai.

In addition to running this picturesque oasis that is frequented mostly by foreigners, the young Afghan manager who has no children of her own has adopted 15 orphans between the ages of 4 and 14, nine of them girls. She also runs a construction company, plans to start another hotel in the central province of Bamyan, and sits on the board of the Afghan Women’s Business Council. And she’s only one of several Afghan women I’ve seen who combine family responsibilities with social, political or business activities.

They’re just the type of people this country needs for its revival, and they have impressed our North American guests no end. One of them said her visit to Afghanistan had been great and will be the highpoint of her life. What more can one say?

Wednesday, 25 June 2005

President Karzai has ordered the release of the imprisoned journalists, Mir-Hossein Mahdavi and Ali-Reza Payam-Sistani, but has said they should be tried in court. He said he had ordered their arrest after reading the articles which are considered by some to be anti-Islamic, but was now ordering their release because the editor had said in interviews that he respected Islam.

I am impressed that with all his duties and visits across Afghanistan and the world, Mr Karazi has the time to read articles in obscure weekly magazines and follow the statements made by their writers. One Afghan reporter who was covering Mr Karzai’s latest decision said, cynically perhaps, that the president ordered the arrests a week ago on the eve of his visit to Iran and was now releasing them just before he sets off on a trip to the West.

Freedom may not be very different for the two from the ‘protective’ custody under which they are being held. It’s hard to imagine that the half dozen powerful and influential religious and political leaders, Shia and Sunni, who were described as ‘infidel’, ‘blood-thirsty’ and ‘corrupt’ will let this matter go by so easily. It is also difficult to guess the degree of protection the two can have outside prison. There are not many people around – other than Mr Karzai’s own huge, heavily armed American body-guards, hired by a private company – who could to the job. Will two newspaper writers be considered in the same risk category as the head of state?

Of course what happens depends to some extent on what the two men are going to do outside prison. Write? Give interviews? Saying pretty much the same as what got them into trouble in the first place? Judging by Mr Mahdavi’s increasingly defiant interviews, he is likely to carry on as before, especially now that the two men have the UN’s support.

Mr Sistani, whose name was given by the BBC Persian Service as ‘Poudineh’, has not been saying much but may well do the same as his friend. Mr Sistani’s wife, who had contributed to the banned paper, has said in interviews that he does not regret what he wrote because he had thought it all through. She has also said that her husband’s views are shared by ‘all those who are intellectuals and who think correctly.’

Thursday, 26 June 2003

This has not been a lighter work day, but not completely free from adventure either. No sooner have we finished with the Afghan Women’s Business Conference and Exhibition than we’re working towards next week’s Afghan Women Journalists Forum’s 1st Consultative and Educational Conference. This is a project we’ve been working on for more than two months and about which I have written before. More than 120 women are expected to attend the conference, some of them, I understand, coming from their provinces to Kabul for the first time.

The programme includes discussions about journalism, trade unions, women’s rights, discrimination and violence against women, and women in art and literature. The range of speakers, some of whom I know personally, is impressive. The discussions are going to be interesting, especially in the light of the ongoing controversy over the two Aftab journalists – at least one newspaper has criticized them for ‘having stirred up a debate that Afghanistan did not need at all’. Even setting aside the content of the conference, the fact that Afghan women journalists are coming together for the first time is going to be significant.

For lunch I went over to Aina Center at the invitation of two Iranian colleagues who’ve come over from France to teach computer skills. We sat at the same table where President Chirac’s wife, Bernadette, had been entertained a few weeks ago, with gourmet dishes prepared under the Iranian computer specialist’s supervision. The food today was lovely and the fruits even more delicious. The background music was from Armenia, with melodies that you could hear in Azerbaijan, Georgia or Iran.

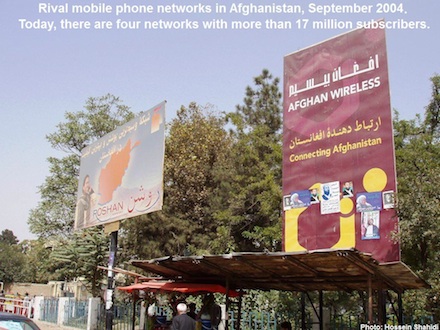

There were about ten of us round the table. Usually, I was told, more than twice that number have lunch at Aina. Those missing today’s meal were over at the Iranian kabab emporium, Shandiz. What had taken them was not so much the kabab pilgrimage, although that’s as much of an incentive here as anywhere else in the world. The occasion was the launch of Afghanistan’s second mobile network, called Roshan, or bright.

The current network is run by a company called the Afghan Wireless Communications Company, AWCC. The network has sold too many subscriptions, with the result that you often have to try a call at least three times before it goes through. The call can break down at any point, necessitating another painful round of re-dialing. Reception is limited and sometimes when calling one phone in a room from another phone in the same room you get a message saying ‘the number you have dialed is out of range’, or ‘the person you have called may have left town’.

The new network is owned by a company 51% owned by Agha Khan, the leader of the Ismaili branch of Shia Islam, most of whose followers are to be found in Tajikistan and northern and eastern Afghanistan. ‘The Ismailis,’ Ehsan once remarked, ‘worship Agha Khan as if he were God.’ I suggested that if he could really get the mobile phone network to run, he would probably deserve to be worshipped.

Friday, 27 June 2003

A very long Friday – 7:30am to 6pm – was filled with translation and layout of a three page document, one meeting with a senior official from our headquarters in New York, and a half hour journey through four Iranian satellite channels from California. These were discovered thanks to Soroush’s patience and we had great fun watching them.

One channel had an Iranian estate agent in California for a guest, but he was being interrupted all the time by the presenter, who kept praising him for his services to ham-vatanan, or fellow-countrymen/women. It was not quite clear which countrymen/women he was referring to: Iranians in Iran, Iranians in the US, or perhaps Americans in the US.

Another channel played a taped interview with an Iranian estate agent in Dubai who was advising his ham-vatanan how to buy property and get a residence permit in the Emirates and use the property as investment. The California-based presenter of the programme referred to this interview not as an ad, but as a ‘report’. The piece was a reminder of the shifting global horizons of at least some Iranians. Under the Shah, Iran was to overtake Switzerland. After the Revolution it was first designated the centre of the universe, but under President Akbar Rafsanjani, South, or maybe even North, Korea became the model. Now, there are Iranians who wish Iran could reach Dubai’s level of development.

A third channel had a rough-looking Iranian preaching Christianity by advising the viewers to ‘cleanse our heart of all filth and dirt, so we could invite Jesus to enter it’. It was very hard-sell for a religion which is supposed to all about love and gentleness. But that must be the US style, and the man was not too far removed from some evangelical broadcasters I’ve seen on American channels.

The fourth channel had a pretty woman with the impressive skill of talking absolute nonsense for long stretches of time, apparently without any notes. One monologue concerned ‘deep thoughts about the deep concepts hidden in the depths of our minds, which take a lot of deep thinking to discover.’ She also spoke of the inability of a fish to stay out of its tank, the swimming pool – yes she said that – or a pond long enough to get an overall view of the world in which it had been living. This, said the lady, was because the fish did not have the intellectual power for such an exercise.

In addition to poor content and presentation, all four channels also suffered from miserable sets. Three seemed to operate out of boxes not much bigger than a London Underground photo-booth. The assertive Christian preacher was doing slightly better, probably because he seemed to be using his own living room.

Meanwhile, on one satellite channel from Iran, where the studios are a lot bigger, there was a round and strange looking presenter conducting strange interviews. One segment, about local cuisine in the city of Bam, in south-eastern Iran, had been shot in an American-style diner. Our presenter had as his guest a young woman, presumably from Bam itself, wrapped up in several layers of visually protective clothing. She said her favourite dish was pizza.

The Iranian news channel had a discussion about industrial investment with a presenter and two guests, none of them displaying signs of great intellect, information, interest or even life. Luckily the caption on the screen made it clear that this was a ‘live’ broadcast, rather than coming from a cemetery. ‘Undead’ would have been a more appropriate description for this particular broadcast.

Saturday, 28 June 2003

Having been rather unkind to some progrmames on Iranian television – not the California ones – I must say that some of their news programmes are not bad at all. Last night they had a report on the fighting in Liberia, from a woman correspondent in North Africa. She sounded confident and her copy was good. A revival, perhaps, of the Iranian media’s old habits of good international coverage to make up for the limitations of reporting domestic affairs.

My major achievement today was to meet the Afghan film director, Siddiq Barmak, whose film Osama won an award at the Cannes festival, and to arrange for his film to be shown tomorrow evening at the end of the first day of women journalists’ conference. He was a very sweet and kind man and gave me the good news that at this year’s Cannes festival there had been five Persian language films. I had known of only two, his own film and Samira Makhmalbaf’s, also about Afghanistan. Mr Barmak informed me that the other three films had come from Iran. Local and international greed and politics apart, common language and culture seems to have brought our peoples a lot closer than we have been for many decades.

At the end of the day I went to check the venue of the women journalists’ conference, Spinzar Hotel, right in the center of Kabul, in the midst of crowded streets and markets with pockmarked buildings and all sort of debris everywhere. The hotel, whose name means ‘White Gold’, a reference to cotton, is a modest but decent place where the delegates who have come from the provinces – and they are a joy to meet – are staying. The hotel has three restaurants, one on the ground floor and two on the fifth floor, one of which is going to be our conference hall. The view from the windows should be marvelous when Kabul has been repaired, re-watered and re-planted, with less pollution blanketing the mountains.

On the walls of the conference hall there were banners with slogans about journalism and respect for truth. Credit was paid to the US Agency for International Development, or USAID, that finances my part of the UNIFEM project, but UNIFEM’s own name was missing from the banners. To avoid a diplomatic and office politics catastrophe, I asked our Afghan colleagues to do something. And they did, as they always do.

They went over to the sign-maker’s shop and got there just as he was closing. Having worked with them in the past, he was kind enough to ask his 14-year old son, Mohammad-Faheem, and his 15-year old apprentice, Ahmad-Zahir, to go along to the conference hall and put defence mechanisms in place. The two boys looked much younger than their age, like 50% of Afghan children whose growth is stunted because of malnourishment. They also worked with some kind of paint with a strong smell which may well have contained toxic ingredients.

Calmly, carefully and beautifully, they added UNIFEM’s six letters to each of the six banners. Their old, tattered clothes, unkempt hair and the elder boy’s sunken eyes had no relation to the artistic quality of their work – freehand drawings that rivaled stenciled ones. All this without saying a word in the whole 45 minutes they were working.

It is thanks to such craftspeople that this part of the world has so many beautiful mosques and other buildings that have survived centuries of natural and man-made disasters. Both boys go to school, 7:30-11:30, before going to work. How long they can do this and what will become of them, I have no idea, but I have plenty of hope.

Let me finish with the happy news that an Afghan mother of three who is in need of a heart operation now has enough funds for her treatment. She is due to be operated on in the next week or so. The Afghan women who have been raising funds for the operation have suggested that the names, pictures and biographies of those who have made a donation should be placed on a web-site. I said I would ask those concerned, but doubted very much that people would want such a private matter to be given a public image. What is impressive, of course, is the generosity of spirit of the women who think they have to go to such lengths to thank people who have done no more than perform a simple human duty.

***