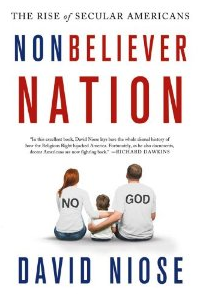

According to David Niose, the author of a newly released book entitled. The Nonbeliever Nation, something unprecedented has happened on the American political scene over the past three decades—the infiltration of the Religious Right into mainstream American politics. By comparing the views of the early 20th century presidential candidates on issues related to religion with those of the Republican candidates in the 2012 presidential race, Noise concludes that “when compared to today, these statements of long dead public figures reveal the travesty of contemporary American politics and public dialogue” (p. 3). For example, he quotes political candidate Rick Perry who once commented on evolution: “God may have done it in the blink of the eye or he may have done it over this long period of time, I don’t know. But I know how it got started”(p. 4).

The author asks a number of salient questions regarding what seems to be the evolving marriage of religion and politics. Is a nonreligious worldview un-American? Is religiosity a prerequisite for sound public policy and for patriotism as Republican candidates for public office want us to believe? Are religious people justified in mocking opposing ideologies while expecting everyone to respect theirs? Is growing secularity in America a reaction to the increasing Religious Right? These and many similar questions have been addressed in this book. Mr. Noise seems to argue that religious institutions, believed to be sacred and infallible, have been dominating human life uncontested for thousands of years. It is time now to question their soundness or their suitability for the modern era. Discernibly, it may take centuries of scientific discoveries and the courage to reform or abolish religious institutions altogether since they have been deeply ingrained in human minds and have crept into almost every facet of human existence.

Noise argues that there are two types of secularity, social and personal. While social secularism entails separation of religion and politics, personal secularism means having the freedom to choose any religion, or secularism, without fear or obstacles. He believes that, because of fear mongering and the marginalization of secularity by the Religious Right, a considerable number of Americans have chosen not to identify themselves as secular, despite having high regard for it. He says the number of secular Americans ranges from 12% to 18% of the population (p. 14). This number is, however, an underestimation. As he states in this book, a larger number of Americans are secular, but they refuse to reveal their secularity because there is a stigma surrounding atheist identity in America. In addition, the number of people who identify themselves as religious is inflated because most people who are not religious, or are marginally attached to a religion, declare themselves to be religious. The most obvious evidence for this claim is the number of regular church goers, which is less than half of the U.S. population.

The author claims that many Americans have distorted views of secularity because they are ill-informed or brainwashed by the Religious Right. Even though some polls show that America is predominantly a religious country, many so-called religious people only superficially subscribe to the pillars of a religion so as to protect their interests and to avoid being ostracized or harassed. They just blindly follow the basic rules without bothering to think deeply about details or dare to question the magisterium of religious laws. This is especially the case in countries dominated by religious fanatics who lack rationality and resort to force and violence to silence critics just because they do not conform. These non-believers, therefore, prefer to remain anonymous in order to remain safe. Noise argues that one of the main reasons secularity has remained in the closet in the US is only because “there were few efforts made to promote humanist identity or any other secular identity on a mass level, nor was there any serious effort made to convince the general public that rejecting theism was acceptable” (p. 17). Because secularism remained dormant and inactive, “the ground was fertile for political mobilization of religious conservatives” he argues (p. 17). The riots and massive violence that erupted in some Muslim countries following the publicity of the video clip The Innocence of Mv,

According to a public survey conducted by Gallup, while 92% of Americans still believe in God, only 41% of them attend church and pray at least once a day. This percentage is inversely correlated to economic condition and the level of personal income, with 64% having an income level of less than $30,000 and only 48% having more than a $100,000 annual income. Further inquiry into the same survey reveals that the percentage of people who pray frequently is high, at least 70%, in low-income states such as Mississippi, Louisiana, Arkansas, Alabama, and Tennessee, while this percentage is much lower, between 40% and 50%, for high-income states such as Massachusetts, Maine, Connecticut, Alaska, and New Jersey. Such findings lend support to the proposition that the degree to which people practice a religion varies indirectly with the level of their income. These findings also help to explain why, in economically advanced nations like the U.S., the percentage of people believing in the core ideas of religion and belief in God is so high; this is chiefly because believing in God has no cost, but instead has a lot of social and personal benefits. However, when it comes to fulfilling the stringent requirements of belief, the percentage of followers shrinks to a lower level as the opportunity costs of doing so rise.

iose seems to argue that religious adherence in America is like many economic problems; they move in cyclical fashion through time. He offers the example of the emergence of Jimmy Carter in 1976 following the revelation of the Watergate scandal. Watergate represented a breach of public trust and morality codes, and this helped Carter, who holds some religiosity, to be elected. This seemed like a breath of fresh air to many Americans who were worried about being threatened by secularity. People at that time thought that this mix of religion with politics was a unique contemporary phenomenon that would quickly dissipate, but they were wrong. Even though Carter only lasted one term, with the emergence of religious organizations such as the Moral Majority, the road was paved for the election of Ronald Reagan in 1980. However, as the author asserts, the election of George W. Bush was a wake-up call. George W. Bush not only played into the hands of the Religious Right, “he belonged to it” (p. 25). He celebrated anti-intellectualism. Noise believes that the time is right for secular Americans to come out and become active, instead of watching the Religious Right claim superiority, because “the continuing rise of secular Americans has ramifications that go far into the future, affecting all facets of public life, including questions of war and peace, foreign-policy, economic policy, education, church and state, the role of government, and innumerable others” (p. 28).

The silence of secular people and their inactivity have led to their marginalization and have fostered the emerging power of the Religious Right which espouses the belief that believing in God is synonymous with morality and righteousness, and secularism means chaos and wickedness. The main reason that America seems to be highly religious, according to the author, is the prevailing view that “being a religious peoples make for a better society, that America’s economic and military greatness is the reward for its piety or part of divine plan” (p. 31). He, nonetheless, challenges the notion that America is a religious country as popularly believed. Actually, it is not, he declares. Even if it is, it should embrace secularism not trivialize it. Noise offers observed evidence that shows the link between the level of religiosity and instances of homicides and other crimes, not to mention the widespread violation of human rights in many societies declared to be religious or are governed by religious rulers. Iran and Saudi Arabia are two prominent examples of this. These are facts that the Religious Right should not ignore and cannot invalidate. Even though these two countries are run by theocratic rulers, they both have oppressive regimes that undermine even the most basic of human rights and punish violently those with opposing views. Statistical data show a strong correlation between homicide rates and certain religious beliefs. The vicious attack on a school bus by the Taliban in Pakistan and the shooting of Malala Yousafzai, a 14-year-old girl whose only crime was encouraging girls to go to school, are the latest instances of innumerable atrocities committed in the name of the religion Islam. Likewise, we have the story of a young 23-year-old woman in Somalia who said she was raped and, consequently, was stoned to death by a group of angry, ferocious men in front of crowd of approximately 1,000 spectators. Such abhorrent scenes can also be seen in countries that are ruled by religious zealotry. While countless cruel acts are committed in the name of religion every day, Noise states, and accurately so, that not even a single individual is killed in the name of secularity or atheism (p. 46).

The primary reason why the Religious Right tries to link secularity to immorality and crime is Just to create fear or to prey on the vulnerability of ordinary believers. Noise asserts that ordinary believers vote massively, but secularists have no major voting power. The Religious Right wants to pretend that America is a religious nation; after having spread fear about secularism, “religiously motivated politicians and activist have little difficulty selling the Christian Nation lie”(p. 51). The author of The Nonbeliever Nation argues that even the U.S. Constitution is God-free and there is no requirement that any government official even mention the name of God when being sworn into public office. The “God Free Constitution demonstrates that the founders intentionally constructed the country upon a secular foundation” (p. 53). The author presents evidence to support his argument that “the Enlightenment was the philosophical foundation upon which America was built, and it is this starting point of a rich secular heritage” (p. 65).

Niose maintains that even if America has a religious heritage, which he doubts, it is not something to be proud of. He states: “Although America does indeed have a noteworthy religious heritage, that tradition has frequently been cringe-worthy and nothing that should instill pride” (p. 70). Even if religion was a positive force at the early birth of this nation, we must concede that it can no longer play that role. Believing that America is a religious nation “is nothing but a myth that is kept alive always through ignorance and religious zealotry” (p. 73).

The author argues that the Religious Right obviously musters power and votes by associating secularism with communism, crimes, and morality. By attributing righteousness and all good things to God, religious people want to draw the conclusion that, without religion, society will descend into chaos and unruliness. When comparing the least religious countries with the most religious countries, real life observations reveal the opposite. The average homicide rate in the least religious countries is approximately 3.5% per 100,000 inhabitants, whereas the rate is almost 10% per 100,000 inhabitants in the most religious countries.

Is immorality an outgrowth of secularism? Let’s find out why religious people are so adamant about supporting their ideas, no matter how nonsensical, that they do not mind harming or killing the opposition for the sake of their beliefs. Niose argues that the accusation made by religious people that secularity is the source of immorality and chaos in the society is nothing but wishful thinking for three reasons. First, empirical evidence shows that social ills such as crimes are more prevalent in highly religious countries, as the previously mentioned statistics indicate. Second, a positive correlation between secularism and economic well-being has been established by empirical data. And, third, religious morality is derived from medieval standards, texts, and tribal traditions which are often incompatible with modern societies, while secularity is a modern phenomenon based on a scientific worldview. “There can be no doubt that for some people, religion provides grounding for ethical behavior, but it would be a mistake to conclude that religion is necessary for morality, or without religion there would be moral decay.” The development of religion and its theocracies, was the answer to humanity’s big questions, questions that could not be answered by our ancestors who lacked scientific aptitude. Our ancestors related everything to God and thus created religion and theology. In modern times, with scientific discoveries, we have been able to finally provide understanding and real answers to many of life’s big questions. Give science a few more centuries and we will find the answers to the rest of our unanswered questions. Conservative politicians, who are in bed with the Religious Right, deny scientific facts such as global warming, overpopulation, and evolution. They consider these to be mire hoaxes. However, finding themselves unable to validate their claims, the ultraconservative politicians can only resort to fear mongering and the spreading of absurd claims.

David Niose offers secularity as a valid worldview of the future and as an alternative to the prevailing religious paradigm. As he puts it, this worldview “represents the best hope for the future of humanity” (p. 206). He says the fact that only a small percentage of the American population attends church is a testimony to the fact that people no longer believe that the traditional congregation is not as essential as it used to be. In this age of a hyper-connected world of wireless communication, the Internet, and social media people can communicate, exchange ideas, and form community in a virtual world. The traditional congregation is no longer a necessary means of forming a community. Today, modern communication vehicles provide unprecedented opportunities for people to congregate and these seem to be steadily replacing weekly religious services. If this shift in community formation continues to materialize, secularity will be gradually transformed into another religion.

The big question for Niose is should nonbelievers, who are seeking recognition and want to be counted, emulate the time-tested religious traditions and copy religious institutions since these have done such an effective job, for thousands of years, of bonding people together and providing them with a sense of belonging, comfort, serenity, and hope? He argues, at the end of his book, that in modern society, the traditional services provided by religion are now being provided by government or nonprofit institutions. We can find communities that can be developed “outside the parameters of religious beliefs or identity” (p. 208).

David Niose envisions that secularity, which is based on reason and critical thinking, will ultimately delegitimize anti-intellectual efforts. He blames the polarization of American society on the Religious Right and believes “one major step that America can take toward addressing these issues is the simple act of acknowledging the validity of secular America” (p. 211). Although religion may not be totally responsible for the polarization of our American society and for its intellectual inaptness, the increasing power of the Religious Right has no doubt contributed to it. But, again, the big question is how can a person discredit religion and explain to fundamentalists that religion is not good if doing so will jeopardize their safety and survival? No matter how logical David Niose’s arguments may be, I think the majority of American voters are still influenced by their religion in both their public and private lives, and this is no less true when they cast their political ballots.

This article has been published simultaneously in Op Ed News