The legs of the acrylic wooden console table that Ramin Haerizadeh has stuck to the canvas of We Choose To Go To The Moon still bear the price tags from the local hardware store from which it was bought. The distinctive font of a local newspaper (in English) can be identified beneath layers of collaged images, and, in the background, familiar architecture from the Persian Gulf region is just about discernible behind what is ostensibly a war-torn landscape made from cut, pasted, and manipulated photographs of bombed-out buildings. But these visual clues are a minor diversion; they are a kind of wink to viewers in Dubai, where Haerizadeh’s exhibition opened on September 13, as if to remind them that the artist a ‘local’.

The table itself is piled with fake plastic fruit, and, from this sculptural centre-point, a torch-beam stream of images projects towards the top corner. Snippets of skin and body parts are visible: an eye, an ear, and an arm, while at the front, two hands hold up a swaddled baby. Are we, one might ask, supposed to be questioning the fragility of life or witnessing some kind of new-age Messiah growing out of the soil? There are, of course, no answers to these musings, neither from the viewer nor the artist himself. Haerizadeh is not one to postulate on concepts – he even shuns the idea of authorship, seeing his artworks as constantly fluid objects that he visits and revisits over the years until someone buys them; it is almost if they are human companions. In this respect, the very act of hanging them on the walls is a performance.

The gallery’s press release describes Haerizadeh’s studio as ‘a theatre of the absurd, a space in motion transformed by the tension between play and acting, which is later converted into collages, diaries, and objects, or actions being recorded on films or photographs’. The artist himself puts it more simply: ‘I am in a performance all the time’. He describes his daily life as a strict ritual that involves waking up early, imagining himself as a new persona, and then going about his day in character. During these performative excursions, he collects objects and materials, which are then translated into artworks back in his studio. Often, this process is interrupted and can lead Haerizadeh on explorative tangents. One image, showing an overweight suit-clad man slumped behind a desk in an office, only furnished with plastic wall ornaments that Haerizadeh has inserted into the canvas, was made when his creative stream was disturbed by an unwelcome call from his bank. Titled Even the CEO of HSBC Has a Belly Button, the piece is irreverent and funny, as well as a scathing satire about the kinds of hierarchy society attributes to people in power.

Like any actor in a production, Haerizadeh does not perform alone. He is part of a trio of artists that includes his younger brother, Rokni Haerizadeh, and their friend Hesam Rahmanian, who live and work together and mostly produce collaborative works. ‘We are like the threads of a carpet’, he says, describing their almost inextricable links, making this exhibition seem like a soliloquy in a larger play rather than a solo show.

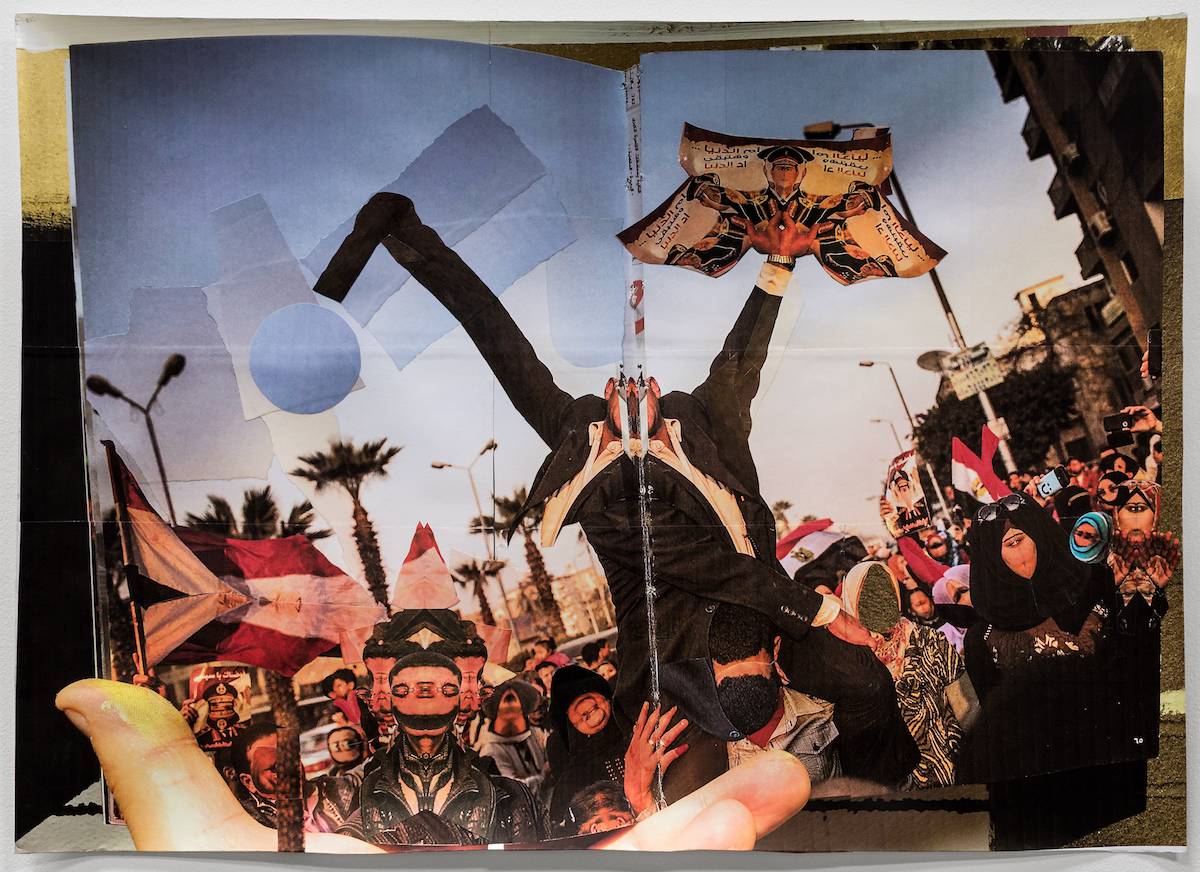

Other pieces in the exhibition include flat pieces from his Still Life series, which he calls ‘studies for a future monument’. The images are made from several parts of other images – mostly documentary photography from times of conflict or protest – and have been collated to make new shapes and forms. War photography, he says, is so often dramatised to resemble iconic paintings from the Western canon. Accordingly, the aim of this series is to subvert the way audiences are used to looking at pictures of war and to inject a good dose of comedic absurdity into them. A fan of Charlie Chaplin films and Samuel Beckett plays, he believes that humour is the greatest levelling plain. In every piece, there is a cheeky smile lurking just below the surface.

Haerizadeh’s skill lies in forcing viewers to unpack their ideas of ‘normal’ and repackage them again to fit in a constantly changing mould

It is typical of all three artists to juxtapose random objects and fuse together incompatible scenarios whilst allowing them to harmoniously co-exist. ‘Sometimes I think it is a mismatched dinner party’, Haerizadeh chuckles to himself as we stand in front of another piece depicting a shopping scene in one of Dubai’s malls, and which has a shelf affixed in front of the wide, gaping mouth of one of his bizarrely faceless characters. Upon it, an empty insulin-filled syringe that used to belong to his mother sits beside a cheap ceramic figure of a topless woman whose breasts serve as removable salt and pepper shakers.

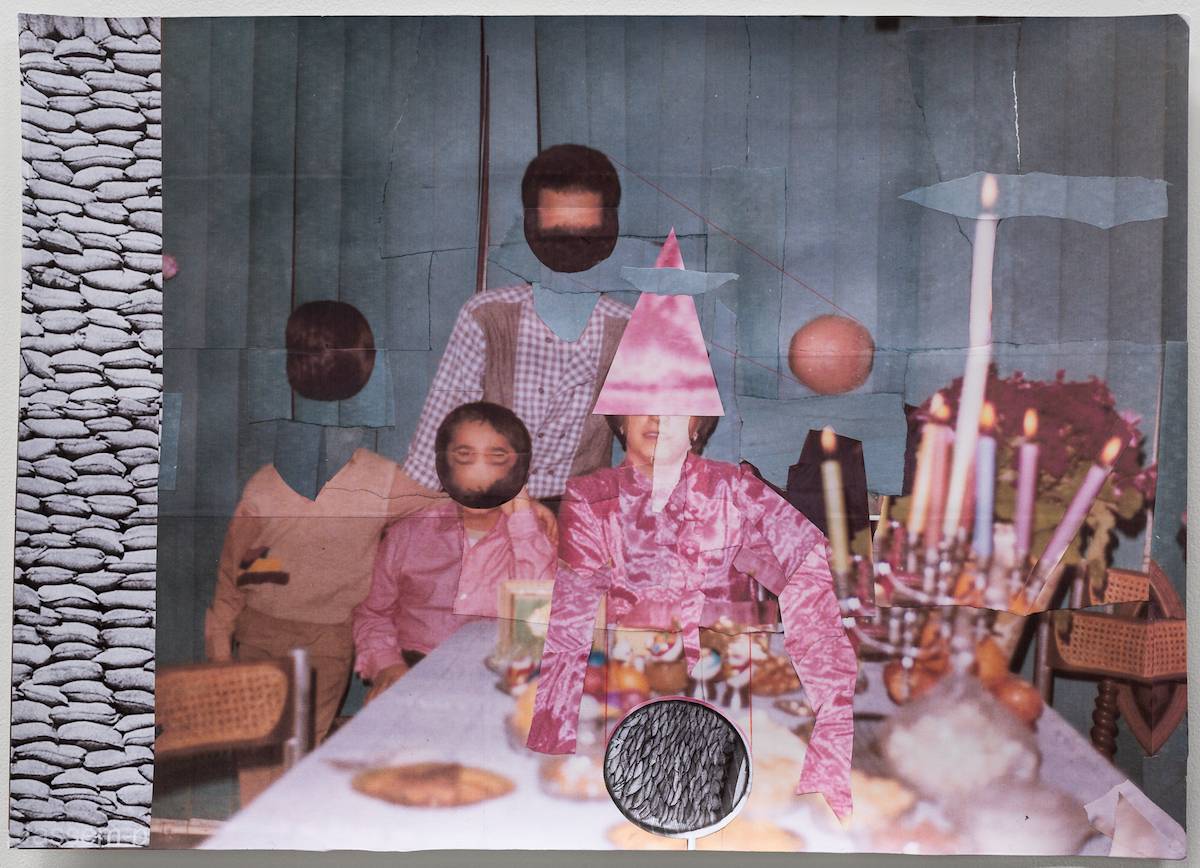

His mother also appears in several pieces from the First Rain’s Always a Surprise series, which also makes use of the photomontage technique. By scanning, cutting, printing, and re-photographing his mother’s old photo albums, he recreates images and scenes that are distinguished by sepia undertones and have an air of nostalgia about them. They are much more personal than any of the other works, but, just as the viewer is lulled into a false sense of security, Haerizadeh carves up the moment by inserting unrelated references or objects, such as the American Hostage Crisis in Iran, D.H. Lawrence’s Lady Chatterley’s Lover, snowy scenes, and birthday cakes.

‘Art is the only medium [that can be used] to express information about several things all at once’ he says. ‘You can say many things at the same time. You can start a sentence in the middle.’ This is, perhaps, the most appropriate way of interpreting the exhibition’s title work – To Be or Not To Be,That is the Question. And Though, it Troubles the Digestion. The show’s namesake, an installation of sorts, consists of a clear plastic chair with images of the torso of an overweight man filling the seat; a plastic watermelon on the floor below it; and behind, a three-dimensional collaged piece with a headless figure standing in a kitchen beside an inverted female in a blue dress, whose head has been replaced by a hand clutching a small bird. The Hamlet-referencing title is an excerpt from a poem by Wislawa Szymborska called Children of Our Age, which asserts that nothing in this era is exempt from politics. The title Haerizadeh chose comes from the middle of the poem, whose beginning reads:

We are children of our age, it’s a political age. All day long, all through the night, all affairs – yours, ours, theirs – are political affairs. Whether you like it or not, your genes have a political past, your skin, a political cast, your eyes, a political slant.

Having left their Iranian homeland in 2009, the trio is always living in the shadow of politics – indeed, as Szymborska would have agreed, something unavoidable in almost every walk of life. Haerizadeh’s skill lies in forcing viewers to unpack their ideas of ‘normal’ and repackage them again to fit in a constantly changing mould. Political or not, this is certainly a victory.

Haerizadeh’s skill lies in forcing viewers to unpack their ideas of ‘normal’ and repackage them again to fit in a constantly changing mould. Political or not, this is certainly a victory.

‘To Be or Not To Be, That Is the Question. And Though, It Troubles Digestion’ runs through November 2, 2017, at Gallery Isabelle Van Den Eynde in Dubai.

Cover image: Untitled (detail; from the Still Life series; courtesy the artist and Gallery Isabelle Van Den Eynde).

Via REORIENT