In his speech describing America’s new approach towards Iran, Donald Trump accused it of responsibility for just about all of the ills of the Middle East and South West Asia. He went as far as accusing Iran of having supported the Taliban and al-Qaeda, sworn enemies of the Shias and Iran.

More seriously, the president refused to certify that Iran had complied with its responsibilities under the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA), thus opening the way for new sanctions and other pressures on Iran. It would also represent a step toward military confrontation, which might start with a direct U.S. attack on Iran or under the guise of anti-terror actions against Iran’s Revolutionary Guards.

Those who focus only on recent developments in US-Iranian relations tend to attribute the current difficulties to the Islamic Republic’s radical ideology and its destructive and destabilizing policies in the Middle East and South-West Asia. They argue that the United States had no problems with Iran before the Islamic Revolution and will have no difficulties with it in future if the current regime changes.

America never considered either Iran or the Shah to be an indispensable ally, like, for instance, Saudi Arabia or Turkey.

Clearly, the IRI’s ideological mixture of leftist notions of the 1960s and 70s and some Islamic principles as interpreted in light of those notions has been hostile to America and its regional allies. Like all revolutionary movements, until the mid- 1990s, Iran also tried to export its ideology beyond its borders.

However, in the last 25 years both Iran’s ideology and policies have undergone changes, and more moderate views, policies, and actors have emerged. Yet, during these years, every time Iran has reached out to America it has been rebuffed. The United States, by contrast, has only approached Iran when it has needed its help, such as during the 1991 Persian Gulf War and briefly after 9/11.

The question thus arises why America has not wanted to reach some form of modus vivendi with Iran. The answer lies in the dynamics of the international political system—and Iran and America’s respective places in it.

The Myth of America’s Friendship with the Shah

Those who bemoan the current state of US-Iranian relations wax nostalgic about the halcyon days of the Shah’s rule. Yet in reality, America never considered either Iran or the Shah to be an indispensable ally, like, for instance, Saudi Arabia or Turkey.

For example, despite the Shah’s pleadings, America refused to sign a security treaty with Iran. It gave Iran pitiful amounts of economic aid and was ready to experiment with social and political change in Iran, while it avoided similar policies in Latin America, Asia, and elsewhere in the Middle East. A good example is the Kennedy administration’s pressure on the Shah to implement far-reaching reforms that greatly contributed to the social and cultural upheavals that culminated in the Islamic Revolution. For its part, the Carter administration pushed a human-rights agenda that gave the wrong signal to the Iranian opposition, and thus helped the Shah’s downfall.

Even regional players, like Saudi Arabia and Israel, which now say how much they miss the Shah, became irritated with him and actively contributed to his downfall. For instance, Saudi Arabia used its oil power to undermine Iran’s economy in 1976. Israel, angry about the Shah’s efforts to reach a deal with the PLO and Syria’s Hafiz al-Assad, used its supporters in the United States to warn against the Shah’s ambitions. In the West, complaints were often heard that the Shah “has grown too big for his britches.” This is one reason why Westerners were so complaisant about events that culminated in the 1979 revolution.

This U.S. approach towards Iran has been the result of its lack of an intrinsic interest in the country. The same was true of Britain. The late Sir Denis Right, the UK’s ambassador to Iran in the 1960s, put it best by writing that Britain never considered Iran of sufficient value to colonize it. But it found Iran useful as a buffer against the competing great power, the Russian Empire. Thus, British policy towards Iran was to keep it moribund but not dead, at least not as long as the Russian threat persisted.

America essentially followed the old British approach towards Iran: keep it semi-alive so that it can put up enough resistance to the USSR until America’s more important and intrinsic interests, such as those in the Persian Gulf, were safeguarded. But Washington never wanted to turn Iran into a strong ally that one day might be capable of challenging America.

In the late 1970s nobody thought that the fall of the Shah would result in the kind of government that emerged in 1979, and especially after the fall of the Bazargan government in November 1979. Rather, most observers thought that monarchy would be replaced with a mildly nationalist, secular government that would continue reasonable relations with the West, without the Shah’s grandiose dreams: something like “Mossadegh Light.”

Iran as Middle Power

By changing the international balance of power and removing the risk of Soviet penetration, the USSR’s fall eliminated Iran’s value to the United States even as a buffer state. In fact, the fundamental shift to a US approach based on the principle of no compromise, can be traced to 1987, when Gorbachev’s reforms began. Since then, the United States has refused to accept any solution to the Iran problem that has not involved the country’s absolute capitulation. For instance, in 2003, Iran offered to put all the outstanding issues between the two countries on the table for negotiations, but the US refused.

After 2003, the American approach shifted from regime change in Iran to gradual and eventual disintegration of the country through the application of crippling sanctions. The JCPOA was designed to remove the risk of Iran going nuclear without giving it any real economic reprieve: it was just enough to keep the country moribund. Thus, it is ironic that President Trump thinks that America got a bad deal.

Ultimately, the United States is concerned with Iran’s potential to become a credible middle power. Great powers do not like middle powers. The latter generally want to be treated as allies and not clients and want their share of the spotlight. The Shah, for instance, had the temerity to want to be treated as an ally and not a lackey.

The same is true of Iran’s regional rivals. They want Iran sanctioned and militarily attacked not because Iran is threatening their security in any tangible way, but because they feel uncomfortable with a potentially powerful Iran. The discomfort extends beyond Iran’s military prowess to its cultural appeal. When the Iranian actor, Shahab Hosseini, won the best actor award in Cannes in 2016, Saudi commentators considered him even more dangerous than the dreaded Ghassem Soleimani, the commander of the IRGC’s Quds brigade.

Any government in a unified Iran, irrespective of its ideology and orientation, will want to realize the country’s potential and be treated as a legitimate regional and international player. Of course, for its part, Iran has to behave according to international norms. But if history is any guide, even when Iran has acted as a stabilizing force in the region, as it did during the 1970s with Western approval, it has been accused of imperial designs and of acting as the gendarme of the Persian Gulf.

The dilemma thus facing the United States, beyond the future viability of the JCPOA, is whether it will be prepared to seek some form of compromise and understanding with Iran, or whether it will try to settle the Iran question once and for all. The latter path, however, is very dangerous and costly, and its success is far from guaranteed. The record of America’s adventures in other parts of the region and the world is far from encouraging.

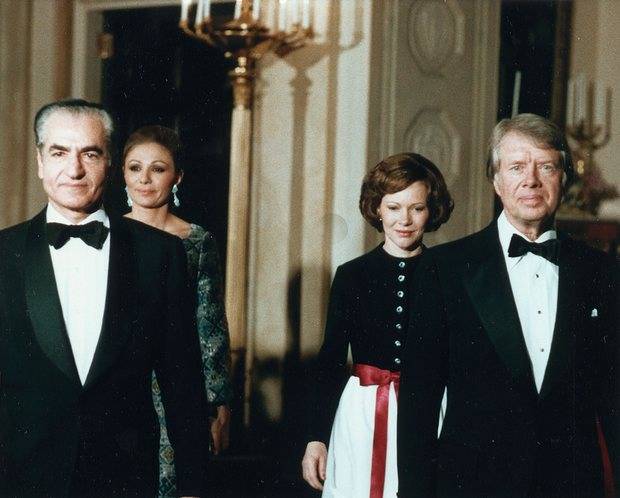

Cover Photo: The Shah of Iran visits the Jimmy Carter White House in 1977.

Via LobeLog