When hackers attacked the Instagram account of popular Iranian musician Shahin Najafi, they replaced Shahin’s profile picture with the flag of the Islamic Republic of Iran. They replaced his account bio with what appeared to be the attacker’s contact information. These other kinds of defacement are typical features of state-aligned cyber attacks and intrusion.

Najafi’s songs address socially and politically sensitive issues such as theocracy, censorship, sexism and homophobia. After the release of his controversial song about a Shiite saint in 2012, two leading Iranian clerics issued fatwas declaring Najafi guilty of apostasy. He received multiple death threats across the social media sphere, and a far-right Iranian website offered a USD $100,000 bounty to anyone who killed Najafi.

He has remained a constant target of hate speech and cyber attacks ever since. Multiple fake accounts have impersonated Najafi and spread negative messages about him. And state-run media have repeatedly conducted smear campaigns against him.

Despite his celebrity status and a clear need for protection from platform operators, Najafi remains vulnerable on Instagram and Twitter. He chooses to remain present on both platforms, despite the consequences.

Najafi is not alone. For several years, Iranian civil society and political dissidents have been top targets of state-sponsored cyber attacks and intrusion campaigns. More recently, these groups have become regular targets of coordinated online mobs that sometimes appear to have links to the state agencies. Many encounter content takedowns and account suspensions that stem from coordinated flagging and reporting of their posts and accounts on social media. They are often impersonated by fake accounts that disseminate misinformation about targets’ private and public lives.

With their privacy and integrity under attack, some end up deactivating accounts. Others restrict the comment section of their profiles. And some seek protection and support directly from social media companies.

What does it mean to be “verified” on social media?

One partial remedy that has helped many public-facing artists, activists and journalists who face such threats online, is account verification — an official signal from the social media company, indicating that a person’s profile is legitimate and that their identity has been verified. When a company “verifies” a user, that person’s profile is adorned with a blue check mark, indicating their authenticity.

In practice, verified profiles enjoy more protection against false reporting and politically driven flagging of content. They appear to have more leverage in mitigating hacker attacks, removing fake accounts or curbing misinformation that could bring them harm. While it is not a panacea, the small blue badge has proven a helpful measure of protection of freedom of expression for its recipients.

But not all those who need this protection are able to get it.

Over the course of 2016, I interviewed 20 prominent Iranian human rights activists, artists and journalists who described challenges they faced in mitigating social media harassment and hacking. The majority of these interviewees had struggled to get the attention of social media companies when they most needed help, and several of them — including Najafi — could not convince the companies to verify their accounts.

Who gets to be verified? How do they do it?

While Twitter offers detailed steps on how to request a verified badge for an individual account, Instagram and Facebook simply explain that verified accounts are only available for “some public figures, celebrities and brands.”

In practice, of those who I interviewed, only journalists affiliated with widely recognized employers, such as large international media houses, were able to easily obtain the coveted blue badge.

All four of the Iranian women’s rights activists and LGBT public figures who I interviewed were unable to obtain verified status, even after sending companies the required documentation. Indeed, for activists, artists and journalists who work in an individual capacity, it is often difficult — if not impossible — to obtain verified status, unless they have a personal contact at the social media company.

In addition to the unclear process, there are other complications.

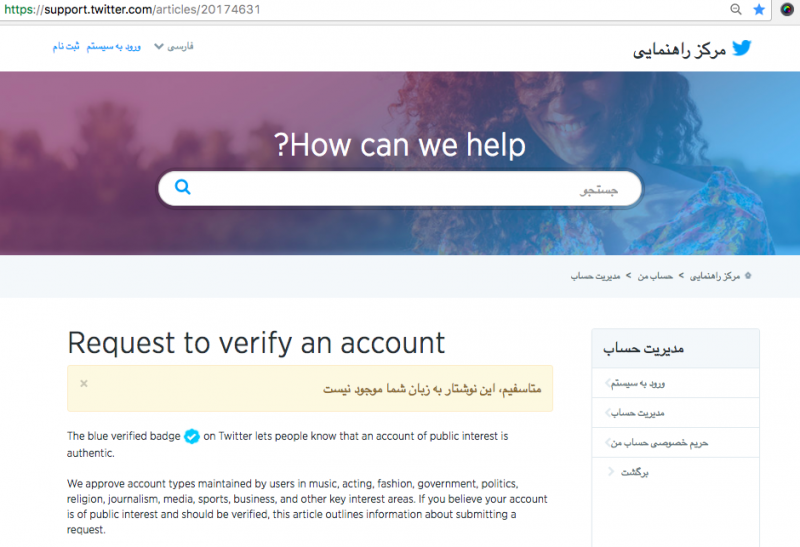

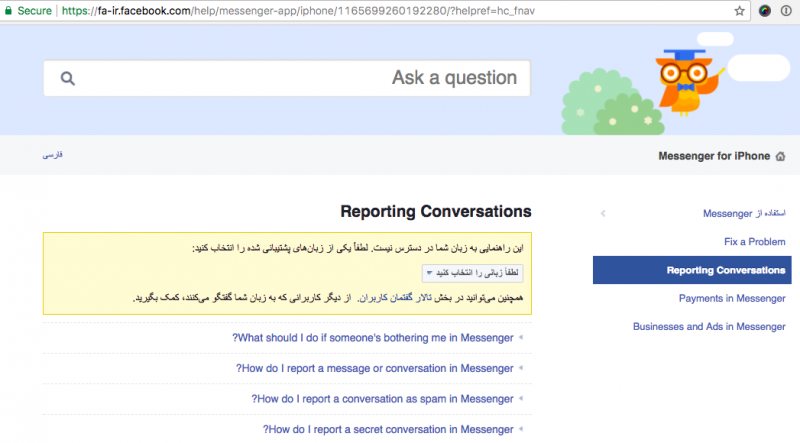

First, these guides are not available in Farsi. And this language gap is not limited to the verification rules — there is no information available in Farsi to guide individuals on reporting and documenting harassment on Twitter, Facebook or Instagram.

This is worrisome for Iranian human rights activists and dissidents who are regularly targeted with harassment and threats through direct messages on Facebook and Instagram, which are among the most popular social media platforms in Iran, and Twitter, which Iranians are increasingly using.

On Twitter, the drop-down list includes 32 languages. But as with Farsi, a handful of these a few generate the same message, stating that content is not available in the language selected. These include Chinese, Bengali, and Vietnamese. Like Farsi, these are all among the 25 most commonly spoken languages in the world, according to UN statistics.

“Major” languages including English, French, Spanish, Arabic, Russian, Japanese, Korean, Hindi and Dutch are all available.

Second, multiple interviewees reported that when they submitted requests for verification to Twitter, they were rejected because they were not “famous enough,” despite their strong notoriety within their country or field.

Social media platforms’ often obscure understanding of the significance of this work and the local context work appears to be keeping these communities from getting these vital protections. It also creates a climate of mistrust between activists and social media companies.

Companies need to understand context

In the past few years, social media platforms have taken noteworthy measures and demonstrated more accountability against harmful speech online. Yet there are still gaps to address, particularly concerning vulnerable communities whose work is deeply influential and not based in the West or conducted in “major” languages. In addition, their audience — and attackers — largely reside far from where major social media companies are headquartered.

These individuals also are often deprived of protection from law enforcement in their respective countries. In some cases, there is even evidence that the government perpetrates or supports the perpetrators of this harassment. This leaves activists even more dependent on the other major power holder in play, i.e. the social media platforms.

More transparency about the dynamics and processing of verification requests and reports of abuse can go a long way toward maintaining trust with end users worldwide. For effective engagement in addressing the concerns of affected stakeholders, companies also must take language, cultural fluency and other barriers into account. Making relevant information available to local communities reflects care and respect for the rights of regular users, not just western celebrities.

Making verification more accessible to at-risk groups is only a partial remedy for the adverse impacts that these individuals endure in the face of harassment. But it can bring a much-needed layer of safety to vulnerable voices who are trying to protect the rights of their fellow citizens.

This essay first appeared in the series “Perspectives on Harmful Speech Online,” published by Harvard’s Berkman Klein Center for Internet and Society. Via Global Voices.