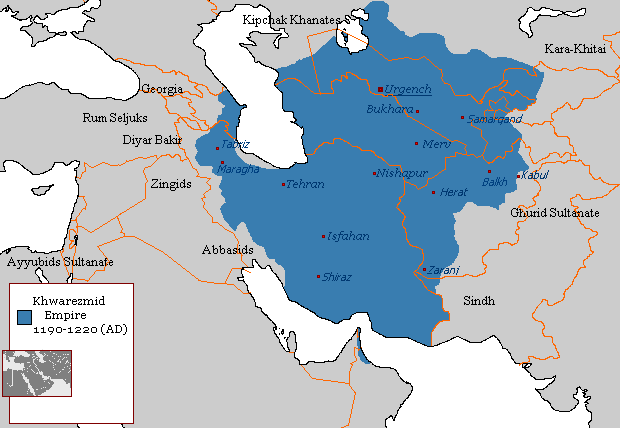

Chengiz Khan’s brutal military campaigns into Central Asia (1219-21), which according to a few historians resulted in the unprecedented massacres of civilians and destruction of major Islamic centres of Central Asia is still hard to fathom. Reading the accounts of what happened it is easy to forget that it’s equally important to realise Ala ad-Din Muhammad Shah, the king of Khwarezm made the attack inevitable. Chengiz Khan was preoccupied with his war campaigns in China and the last thing he needed was a distraction from his efforts in subduing the rest of China, many of whom were the longtime enemy of the steppe people. For the first time under his leadership the various tribes of Mongolia became a united nation and the dream of capturing at least parts of China was no longer a fantasy. Why would he want to be taken away from making that dream a reality?

The trade theory is the most accepted scenario that has been written by historians and chroniclers as the main reason behind Chengiz Khan’s (1162 –1227) attack on the empire of Khawarezm. The invasion itself was recorded by the historians at the time and has been studied and used as source materials by students, scholars and chroniclers of every age.

There have been other possible reasons for the invasion, for example, did the Abbasids influence Chengiz Khan decision or if Chengiz used the massacre of his traders and envoys as a pretext to invade Central Asia because he was going to expand westward? Although I would touch on some of these questions, however, the trade theory is the main subject of this essay and it is better for other theories to be explored separately.

The Trade Theory

Juwayni (1226-1283) the Persian historian tells us that the governor of Otrar (today’s Kazakhstan. Persian, Parab, later Farab) confiscated the goods of Chengiz Khan traders and arrested them. There were around 450 traders escorted by 100 Mongols with 500 camels. The numbers vary in different sources but all the merchants were Muslims. Chengiz sent Muslims to negotiate trade agreements with other Muslims. A clever diplomatic gesture from someone who was not a Muslim. In the era of religious intolerance it was a sensible thing to do in order to avoid any prejudices that may cloud peoples’ judgement and decision making. It also showed that the Muslims who lived under his rule had accepted his leadership and were ready to establish new trade links with other Muslim people. It is very likely that these traders were the Uighurs (Turckic) and Sogdians (Iranian) traders who were operating along the Silk Road for centuries.

The traders were all charged with espionage by Inalchuq Ghayir (or Qadir Khan). He was the governor of Otrar who ordered their arrest. He should have expelled them from the land if he seriously believed that the charges were true. And as a Muslim he should not have taken their merchandise which were not his. The delegation brought with them expensive range of goods: ‘walrus and narwhal tusks, jade, musk and a nugget of Chinese gold as big as a camel’s hump.’ They were sent by Chengiz to impress the Muslims and hopefully entice them to a trade agreement. He was also simply responding to the initiative made by a few merchants who arrived at his court a few years earlier from Bukhara.

How did Inalchuq justify his decision? This was a caravan of traders, even by Silk Road trade standards fairly large. Was it greed, as it has been suggested? As the Mongols were heavily engaged in fighting in China did he think he could get away with it? Was he envious of the traders who were taking advantage of the latest geopolitical changes brought about by the rise of Mongols? His decision was approved by Ala-ad-Din (1169-1220) the Shah of Khwarezm empire. And even if Ala-ad-Din didn’t agree with the charges he had to give in because Inalchug was Terken Khatun relative, either her brother or nephew. Terken Khantun, the Shah’s mother was the co-ruler of the Khawarezm empire who had given Inaluchuq his post as a governor. Nepotism was also rife in the Khwarezmshah empire where family connections and ethnicity spoke louder than merits.

However, spying allegations were not a strong enough basis for their arrest, even if true, let alone their execution. For traders to report back any useful information from far away lands was a common practice. Ala-ad-Din must have been very familiar with such activities. It was from Bukhara that a trade delegation reached China in 1216 under an official by the name of Baha ad-Din Razi. Their visit was as much about trade as it was about information gathering. Ala-ad-Din wanted to ascertain if the rumours about the fall of Chung-tu (or Zhongdu, present-day Beijing) was true or not. When he later was told that it was true, he was horrified. Chung-tu was famous for its strong fortification and its reputation as being impregnable.

Razi and his small delegation arrived at the Mongol court safely and were received cordially by the officials and even given an audience by the Khan himself. Juzjani (b.1193) wrote of their meeting in which Chengiz was very friendly toward them and welcomed trade relations with the merchants of Khwarezm empire. Under Mongol protection they were also free to move around and explore the places that had become in of their jurisdiction.

Instead of reciprocating the hospitality, Inaluchuq treated the traders like criminals. They were also accused of spreading rumours about the power of Chengiz Khan. But it was not rumour, it was true. The Silk Road had become safer since the arrival of the Mongols. And the more power they gained the safer it became. The traders were hoping to convince people that it has become less dangerous to travel along the Silk Road to trade.

When Chengiz heard about his envoys’ arrest in Otrar he contained his anger and gave Ala ad-Din a chance to make apparitions. Since he was not at war with Khwarezmshah he must have wondered why his envoys and traders were arrested. Considering the Mongols were hypersensitive about their envoy for they never violated the diplomatic immunity given to envoys of other countries, including those nations with whom they were at war, this was a cool headed approach from someone who had a fearsome reputation.

He gave Ala ad-Din the benefit of the doubt. providing him with another opportunity to make amends, even possibly explain governor’s irrational behaviour. Three more envoys were dispatched to investigate the matter. But as they arrived the entire members of the previous envoy and the traders were put to death. And the new envoy had their Muslim leader killed and the other two (Mongols) their beards singed (according to another account mutilated) and sent back to Chengiz. Even by medieval standards this was cruel, and completely unnecessary.

Why did Muhammad Shah interpret every contact from the Mongol as a threat rather than a handshake for a bilateral trade relation or a genuine diplomatic effort for reconciliation? Prior to the incident in Otrar, in a meeting with Razi, Chengiz had called Ala ad-Din his son. Whether it was a linguistic misunderstanding or Chengiz did see himself superior to Ala ad-Din, the Shah’s insecurity got the upper-hand and interpreted it as a threat. Chengiz also expressed his wish of letting Ala-ad-Din be the king of the west (sunset) as he became the ruler of the east (sunrise). Again he thought Chengiz is referring to his own rise and Khwarezmshah’s twilight. Muhammad Shah was more paranoid than MacBeth. Chengiz knew his limitations as the conquest of China was far from over (although more than half of it has become his) why would he want to spread his resources and enter another war so far afield, if it could be avoided.

Chengiz who had promised security for traders under his rule was left with no option but to prove that under his rule traders were safe. And any harm done to them will be avenged. It was a test of his character to those who had given him their alliances and now they were watching him deliver on his pledge.

Mongols’ Relation With Muslims

How did the Mongols right up till the invasion of Khwarezm empire gain a good reputation with many Muslims?

Kuchlug who had managed to become the leader of Qara Khitan after fleeing from the Mongols when his tribe (Naiman) was defeated by Chengiz army back in 1205 posed a threat to the Mongol vassals in Central Asia. Kuchlug as a ruler ‘proved even less tolerant of Islam than his predecessors, and is accused by Juwayni and other Muslim chroniclers of numerous atrocities, including the crucifixion of the Imam of Khotan.’

When the chieftain Buzar (vassal of Chengiz Khan) was murdered by Kuchlug, Buzar’s widow refused to surrender the town, therefore urged Chengiz Khan to come to the rescue. The small Mongol army on a mission to annihilate Kuchlug was hailed as liberators. When the Mongols learned about the treatment of the Muslims in Qara Khitan they declared religious tolerance under the Mongol rule and assured the Muslims they were safe. It is also quite possible that many Muslims joined the Mongol army after the fall of Qara Khitan, since their powerful neighbour Khwarezmshah had made a pack with Qara Khitan’s rulers before and could no longer be trusted and did nothing to help them. This in fact has been confirmed by Juwayni that when Chengiz marched toward Khwarezm territories he was joined by ‘veteran warriors’ from Qara Khitan Muslim population.

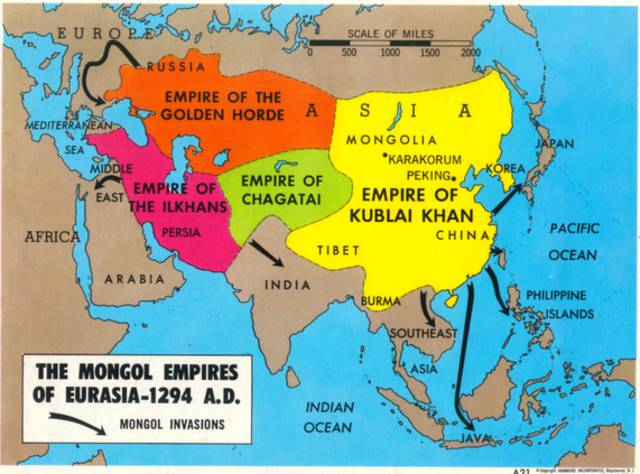

Uighurs, Khitans and Sogdians also came to play pivotal roles in the Mongol empire. As the Mongol territories became ever larger they proved capable in oiling the administrating machine of the empire. The Uighur alphabets was adopted by Chengiz Khan to record the Mongolian language so they could communicate across their vast territories. Rashid-ad-Din tell us during the Kublai Khan (Chengiz grandson) eight out of the twelve districts in China were governed by Muslims. Something unimaginable if the Mongols were not in power. Peers believes Uighurs and Sogdians also provided the Mongol war machine with intelligence since they were the main traders along the Silk Road and had more information than anyone else about the many towns and kingdoms dotted across this long stretch of trade route. It is quite possible that a Muslim by the name of Jafar, was the chief intelligence officer for the Mongols. He had helped Chengiz Khan before when his troops couldn’t get through a heavily fortified and protected Juyong Pass by providing an alternative route around the Pass. Other Muslims, like Mahmud Yalavach, became responsible for the captured Jin territories and his son, Masoud, ‘by the beginning of Mongke’s reign ran the administration for Transoxians, Turkestan, the Uighur terrritories, Khitan, Keshghar, Farghana, Utrar, Jand and Khawarezm.

The merchants (many Muslims) believed safety along the Silk Road will be guaranteed under one ruler and the inter-fighting between various rulers compromised the safety of traders and their livelihoods. Betting on the Mongols to become the top dog was a gamble that paid off handsomely for them. Juwayni wrote, “He [Chengiz Khan] had brought about complete peace and quiet, and tranquility, and had achieved the extreme of prosperity and well-being; the roads were secure and disturbances allayed.”

Shah’s Divided Kingdom

Ala-ad-Din kingdom was a divided empire. Terken Khatun, his mother, was as powerful as her son. Most of the soldiers in his army were also mercenaries from the Terken Khatun Kipchak tribe of the Black Sea region. She could have easily asked the military to get rid of him if any serious dispute between them erupted. She too was not liked much outside the military zone. ‘When the Mongols captured the city of Gurganj (her headquarters) on the Oxus, they found the prison full of Khwarizmian nobles incarcerated for their opposition to her rule.’ Even during her desperate last hours that she had left to flee before Guranj was captured she ordered the killings of some of the prisoners in case they collaborated with the Mongols. We can assume many joined the Mongols when the prison gates opened.

Another unpopular figure was Jala-ad-Din (1199-1231) the only hero in the whole tragic saga. He was the most able leader by all accounts but was not liked among the military elite. His grandmother, Terken Khatun preferred his brother Uzlaq-Shah by another mother (related to her) to succeed his son as king. Juwayni tells us that Jalal-ad-Din had some powerful enemies because he believed in meritocracy rather than titles and family or political connections which had become common practice in the empire. To make the matter worse the Turks and Iranians (Tajiks) were on bad terms. The Ghurids, the last Iranian dynasty was defeated in 1215 by Khwarezshah. The Persian speaking people of Central Asia must have wondered what the future held for them under the Turks.

Just as you would think there was enough division to ensure a terrible downfall in the face of a foreign attack, Ala-ad-Din’s reputation as a Sunni Muslim was in doubt. He opposed the Caliph in Baghdad and even had once marched to assert his power over it, only to be driven back by blizzard. The Sunni population of his kingdom most likely questioned if his Shiite leanings was genuine or it was merely a political ploy to threaten Baghdad with. He had alienated the Sunnies who were by far the majority living in his empire. The Khwarezm empire you may conclude was already in decline and it was only a matter of time before it collapsed, which is why it turned out to be less formidable of all Chengiz Khan’s major conquests.

Ala-ad-Din was effectively the founder of Khwarezm empire. He had started out as a good soldier but neither of his victories could compensate for the disunity among his military elite and his family. His rash behaviour has been difficult to explain. Later he turned out be a coward as well by running away from the Mongols instead of facing them. This was contrary to Jalal-ad-Din, his son, who tried his hardest to save the territories from overwhelming forces. His boundless energy and efforts mounted to nothing. At only 19 Jalal found himself defending a territory against a man who’s empire grew four times bigger than Alexander’s the Great and twice bigger than the Roman Empire, and became the largest continuous land empire ever. What hope did he have in stopping him?

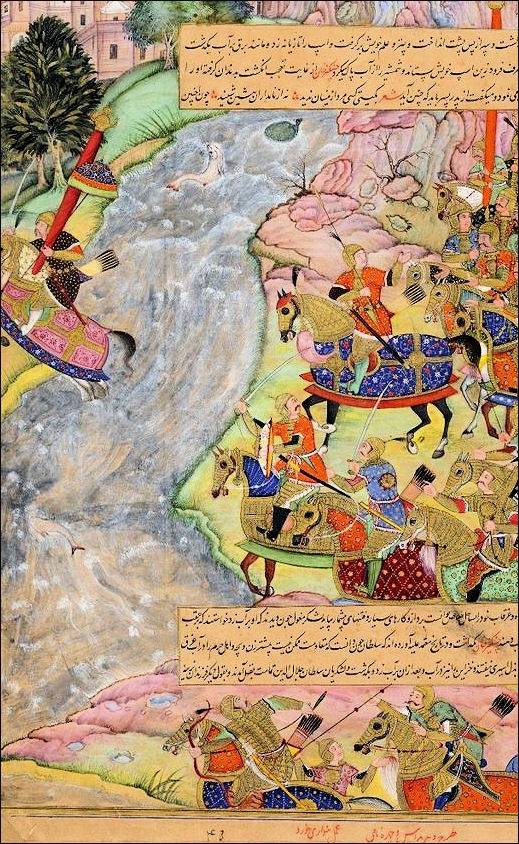

Jalal-ad-Din The Uncrowned King

Chengiz in the battle of Indus, witnessing Jalal’s daring escape by forcing his horse into the river after his troops got routed, admired his courage and let him go. He is reported to have said ‘every father want to have a son like him,’ or another translation, ‘a son like him deserve a proper father.’ This story requires a pause. It is unlikely that Chengiz would have let him go if he had the opportunity to apprehend him but it’s a good way of summing up Jalal’s courage and relentless efforts against the Mongols. The Mongol army had orders to capture Jalal alive. This kind of order was only issued for special reason. For example, they wanted the governor of Otrar alive to punish him for his crimes. Terken Khatun, was also another family member who was spared. She was sent to Mongolia and died some years later. It is possible that Chengiz wanted to offer Jalal-ad-Din a job in his army. “Choosing the right man, Mongol or non Mongol was Chengiz supreme talent,” John Man the author of his biography wrote. If Jala-ad-Din was in command and not his father, Chengiz knew everything would have been different. Not only the outcome of his invasion would have been different but perhaps he didn’t even have to declare war on Khwarezm if Jala-ad-Din was at the helm because his traders and envoys would have been welcomed instead of executed.

Although Jalal had some of his father’s character flaws, he was not a coward and led the resistance for good number of years. He was the type of man Chengiz would have loved to have among his top rank. Chengiz had a very persuasive case to lure him into his camp: he would have reminded Jalal the humiliation he must have felt when his grandmother ‘forced his father to pass over him in favour of Uzlaq-Shah the beloved youngest son of the family, of a different woman, but one who was her protege and servant’. Chengiz would have told him, ‘look, your own father betrayed you by not standing up for you and only used your valour and skills in warfare to advance his military gains. What about the army generals who wanted you dead and your father didn’t have the guts to punish them, in case his own position was undermined. And now where are they? All gone and you are the only person standing. Join me and share in the spoil or die.’

One wonders how Jalal-ad-Din kept going after all the terrible emotional setbacks he had experienced from his own family. Later all his appeals to other Islamic centres that were still intact from Mongol invasion fell on deaf-ears. Ismailis’ spy networks also informed the Mongols of Jalal’s next moves in order to outsmart him. This quite possibly was true, for the Nizaris were the first to send their submission to Chengiz Khan and wanted to eliminate any chance of Khwarezm victory and possible comeback.

Jalal found himself fighting on various fronts – with his energy scattered he never could follow up on any of his victories against the Mongols and finally died in the hands of bandits as he was planing his next course of action.

* * *

Ala-ad-Din unwittingly launched Chengiz Khan’s career as the world conquerer. It opened his eyes to unconquered territories further west. When he discovered all the weaknesses of the Khwarezm empire, the biggest military power in the Central Asia, he learned what is on the map does not necessary correspond with what is happening on the ground.

By killing the traders and envoys, Ala-ad-Din sealed his fate and the fate of Central Asia, Iran and later Iraq. The trade theory tell us that war was avoidable if Ala-ad-Din had acted with some wisdom and followed the diplomatic protocols. The trade theory is the most plausible theory as to why the invasion happened. Although other theories should be further explored, for example, what al-Nasir, the politically minded Caliph was doing at the time. He came to power after a long succession of ineffective leadership. His reign, as the religious leader of the Sunni world was fairly long and he wanted to make Baghdad politically independent. The Abbasids had never been neutral but perhaps during the Mongol invasion they could not have been as active as they wanted to be but definitely hoped for a result that benefited them most. In the past they had supported the Seljuks against the Ghaznavid and then Muhammad Tekish against the Seljuks, incited the Ghurids against the Ala-ad-Din and his father.

Understandably al-Nasir and Ala-ad-Din didn’t meet eye to eye and any help coming from Baghdad was not a hope Muhammad Shah could entertain in his already defeated mind. The very fact that al-Nasir didn’t do anything during the invasion speaks volume. The majority of the Muslims in Khwarezmshah empire were Sunnies and looked up to Baghdad as the spiritual and political centre of the Muslim world and must have hoped for some reinforcements from the Abbasids.

When Ala-ad-Din fled from the Mongols he should have escaped to Baghdad, a well fortified and protected city. The fact that he didn’t, can only show that his life wouldn’t have been safe there either. We are told the thought of going to Baghdad entered his mind but he rode north rather than south.

The Baghdad conspiracy theory still does’t hold up. For two good reasons. Chengiz was not the type of person who would have listened to al-Nasir or anyone else to attack Khwarezm or elsewhere, although most likely he was petitioned by the Abbasids. Also, there is a lack of evidence. The allegations of Baghdad’s hands in the Mongol invasion has been called ‘Persian rumours.’ The fact that it’s been called that means that the vast majority of the people who were Sunnis felt betrayed by Baghdad for not coming to their aid and tried to put the blame on them. Those who felt they had a special relationship with Baghdad realised their bond was a figment of their imagination; so much for the Abbasid revolution assisted by the Khurasanies.

The invasion of Central Asia by Chengiz Khan would have been even quicker with far less casualties if Ala-ad-Din had the courage to face the Mongols in a pitched battle. His war strategy is another very important issue that has to be looked at separately, for it was a deliberate attempt to involve the ordinary population to fight for a king who had already abandoned his kingdom. That’s another tragic story.

Bibliography

Islam, a thousand years of faith and power, Jonathan Bloom and Sheila Blair, TV Books, New York, 2000.

The Mongol Empire, Genghis Khan, his heirs and the founding of the modern China, John Man, Bantman Press, London, 2014.

Genghis Khan: Life, Death, and Resurrection by John Man, Bantman, 2005, London.

The secret history of the Mongols, the life and times of Chinggis Khan, translated, edited and with an introduction by Urging Onon, Curzon, Richmond, Surry, 2001.

The Golden Chinggis, history of Khan The Mongols, by Urgunge Onon, The Folio Society, London, 1993.

Genghis Khan, his conquest, his empire, his legacy, Frank Mclynn, Da Capo Press, Boston, 2015.

In Xanadu, William Dalrymple, Vintage Books, NY, 1989.

The Mongols and the Islamic World, from conquest to conversion by Peter Jackson,Yale University Press, London, 2017.

The Assassins: The Story of Medieval Islam’s Secret Sect, by W.B. Bartlett, The History Press, U.K. 2013.

The Caliphate, Hugh Kennedy, Pelican, London, 2016.

Tang China, the rise of the East in world history by S.A.M. Adsheed, Palgrave, Macmillan, NY, 2004.

A concise history of Russia by Paul Bushkovitch, Cambridge University Press, NY, 2012.

The tea road, China and Russia meet across the steppe by Martha Avery, China International Press, China, 2003.

From the holy mountain by William Dalrymple, Harper, London, 2005.

The Silk Road, a new history of the world by Peter Frankopan, Bloomsbury, London, 2015.

Genghis Khan and the Mongol war machine by Chris Peers, Pen and Swords Books, London, 2015.

The Rise and fall of the second largest empire in history, by Thomas J. Craughwell, Fair Winds Press, Beverly, Massachusetts, 2010.

Online Resources

Iranica

Wikipedia

Brittanica