I must have just finished downing my third cup of bitter Faranseh coffee when Babak finally turned up at the old Hyatt in Tehran. I was feeling rather low, not only because I could barely sense the bittersweet aura the place had once held prior to its godawful makeover, but also because I’d been waiting for what had seemed like ages. I couldn’t blame Babak, though; after all, he’d driven all the way from Karaj to meet me, and I’d have probably totalled my car on the spaghetti-string freeways of the city, let alone drive around in circles for a couple of hours trying to find an eyesore of a hotel. As for our meeting that spring day in 2013 — well, I don’t exactly remember much of what was said between myself and the laid-back, soft-spoken artist, or what was going through my mind at the time. He did mention something about a work involving pickles, though. Anyway, I suppose what I’m trying to say is that, although an admirer of his work, I certainly couldn’t picture him bagging one of the most prestigious prizes for contemporary Iranian art one day. Or perhaps I could, and I’m just drawing blanks now. I must be getting old.

I do, however, recall my meeting with another impressive Iranian (this time, not so soft-spoken or dressed down) quite vividly. In 2015, an artist by the name of Sassan Behnam-Bakthiar got in touch with me regarding my Iran-relating writing. We spoke on the phone at length shortly afterwards, at once expressing our unbridled love for Iran and giving vent to our myriad frustrations with many in the Iranian diaspora; and, before I knew it, I found myself on a little jet plane bound for the sunny shores of a place with a name rivaling Sassan’s in terms of syllable count: Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat. Although it was very much touch and go in terms of my trip (I was there for less than a day), we hit it off remarkably well, perhaps thanks in part to some exceptional rosé ordered by Sassan and his wife, Maria. Again, we discussed our obsession with Iran, as well as our desire to expose to the world its true colours, long overshadowed by misconceptions, prejudices, and ignorance — both amongst non-Iranians, as well as, rather unfortunately, Iranians themselves. It was over a few of the many glasses of wine of the evening that Sassan spilled the beans about his ambition to realise his ideas on a much grander scale. Sure, he thought, his own artistic career was one thing — but it wasn’t enough. What was needed to effectively bring together the cultural efforts of patriots like Sassan and myself wasn’t simply a network, but rather, an institution.

Although we were all heady with rosé, I could tell Sassan was serious about the foundation he wished to establish in Saint-Jean-Cap-Ferrat, where he’s been residing since 2011. As such, I wasn’t at all surprised when, in 2016, he let the world know about the eponymous Fondation Behnam Bakhtiar. Non-political and non-religious, it was founded with the sole intent of promoting the richness and beauty of Iran and Iranian culture through visual art. Like myself, Sassan regards himself as an ambassador of the true spirit of Iran, and, as such, looks at the Fondation as a sort of cultural gateway between Iran and the West, particularly where Europe is concerned.

It is Babak’s belief that the true place of all Iranian émigrés is their ancient homeland; it is there that they are most needed, and where they must play their role, together with their compatriots, in fashioning a brighter future for Iran.

Aside from the Fondation’s impressive collection of works by master artists like Parviz Tanavoli, Shirin Neshat, Farideh Lashai, Ardeshir Mohassess, and Sohrab Sepehri, amongst many others, it is notable for its Behnam Bakthiar Award, which supports — financially and otherwise — emerging artists in Iran and the diaspora. Needless to say, when Sassan rang me up to invite me to serve as a juror for the Award’s inaugural edition, I was only too happy to serve. While I’ve served as a juror on other notable boards, my experience with the Fondation was particularly special, on account of its Iranian connection and the love for Iran shared by Sassan and myself.

As the Fondation had only been established, it was perhaps fitting that, for its first iteration, it would revolve around the subject of the future. Specifically, as jurors, we were to look for artists whose works, in one way or another, looked at the near future of Iran and the possibilities of fostering a better one. Hundreds of artworks had been submitted to the Fondation from around the world, and choosing a winner (and two runners-up) became an even more daunting task after we’d whittled down our list to only a handful of finalists. As part of the process, we judged the works in question based on how well they addressed the subject as set out by the Award, as well as their intrinsic artistic merit. After the scores assigned to each artist by the jurors were averaged out, the gentle artist with a thing for pickles emerged as the first place winner, followed in second and third by Parham Peyvandi and Morvarid K. respectively.

It wasn’t Babak’s ‘pickled’ works that earned him the first edition of the Award, but those from his Anticipating series from 2016. Consisting of an assortment of traditional Iranian doors with superimposed images and glass negatives (painstakingly handmade), the series addresses issues of migration, exile, and displacement, as well as notions of home, which the artist has also dealt with in other bodies of work, such as The Exit of Farhad and Shirin and Alice in the Land of Iran. In these works, Babak uses the house as a metaphor for Iran. Dilapidated and decrepit, they represent — according to the artist — the condition Iran is in danger of succumbing to lest its children continue leaving the country, and those who have already left do not return. It is Babak’s belief that the true place of all Iranian émigrés is their ancient homeland; it is there that they are most needed, and where they must play their role, together with their compatriots, in fashioning a brighter future for Iran.

As an unconditional lover of Iran who has lived all his life in the West, I can only feel shame and embarrassment at Babak’s sentiments. It is indeed difficult to disagree.

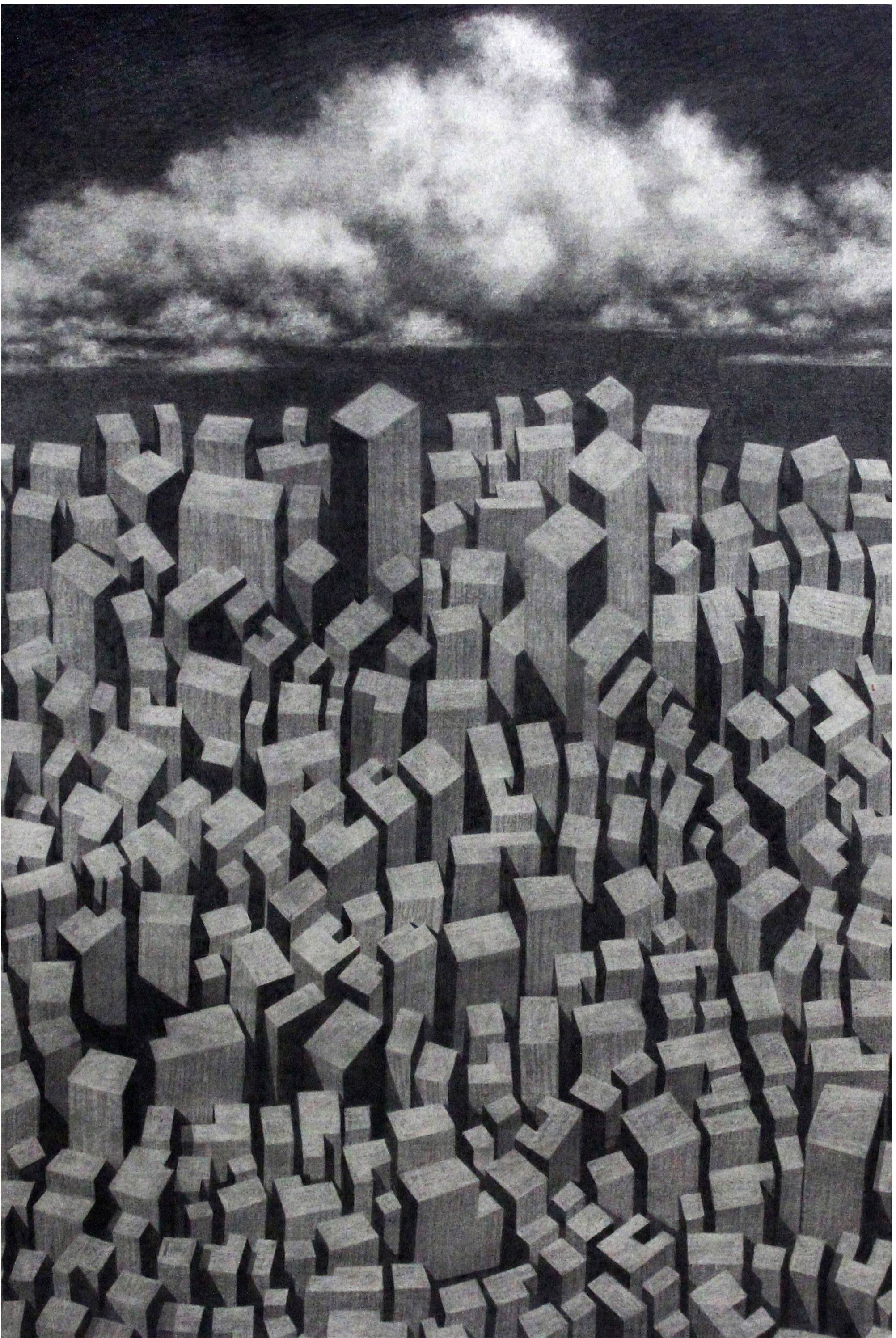

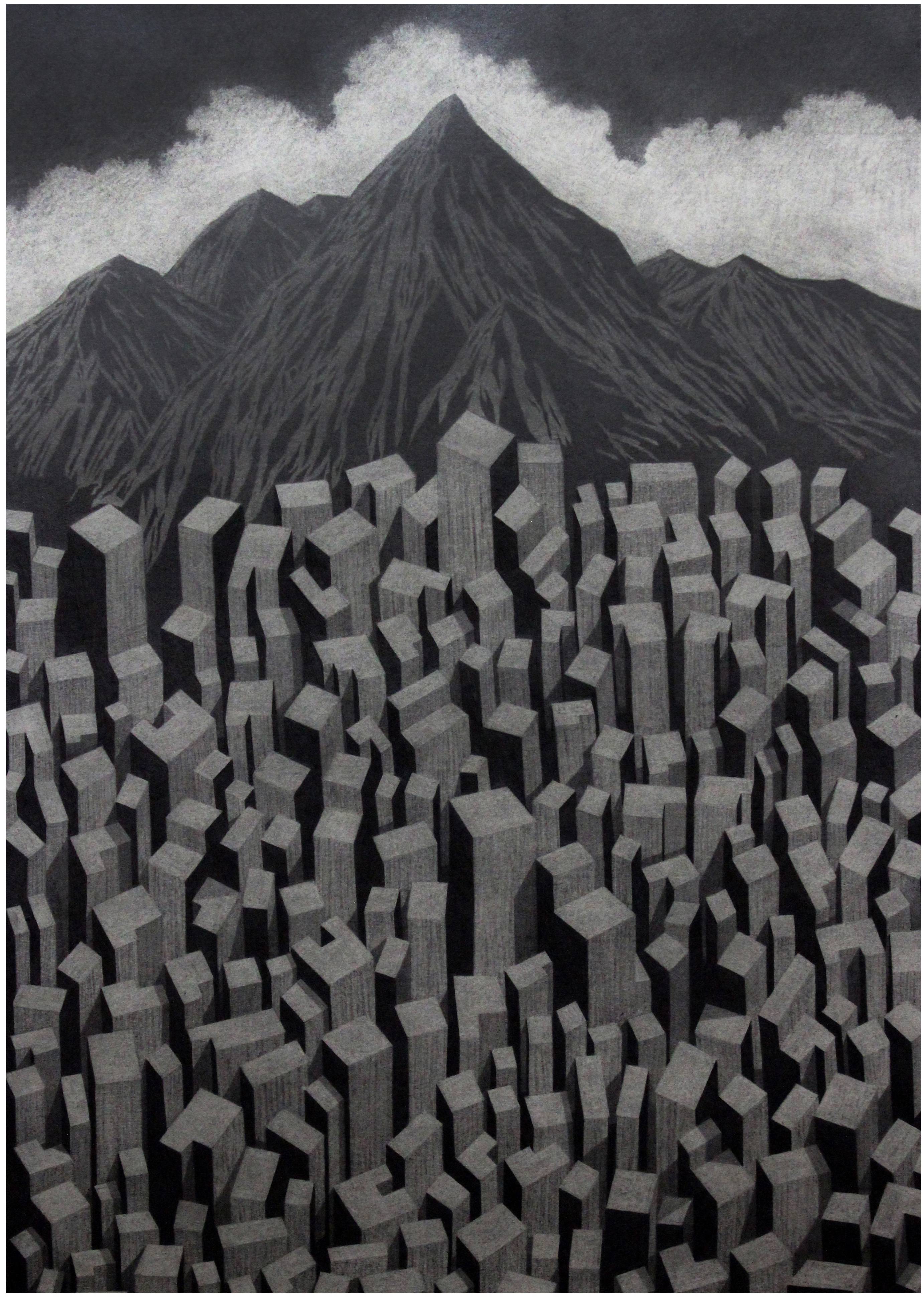

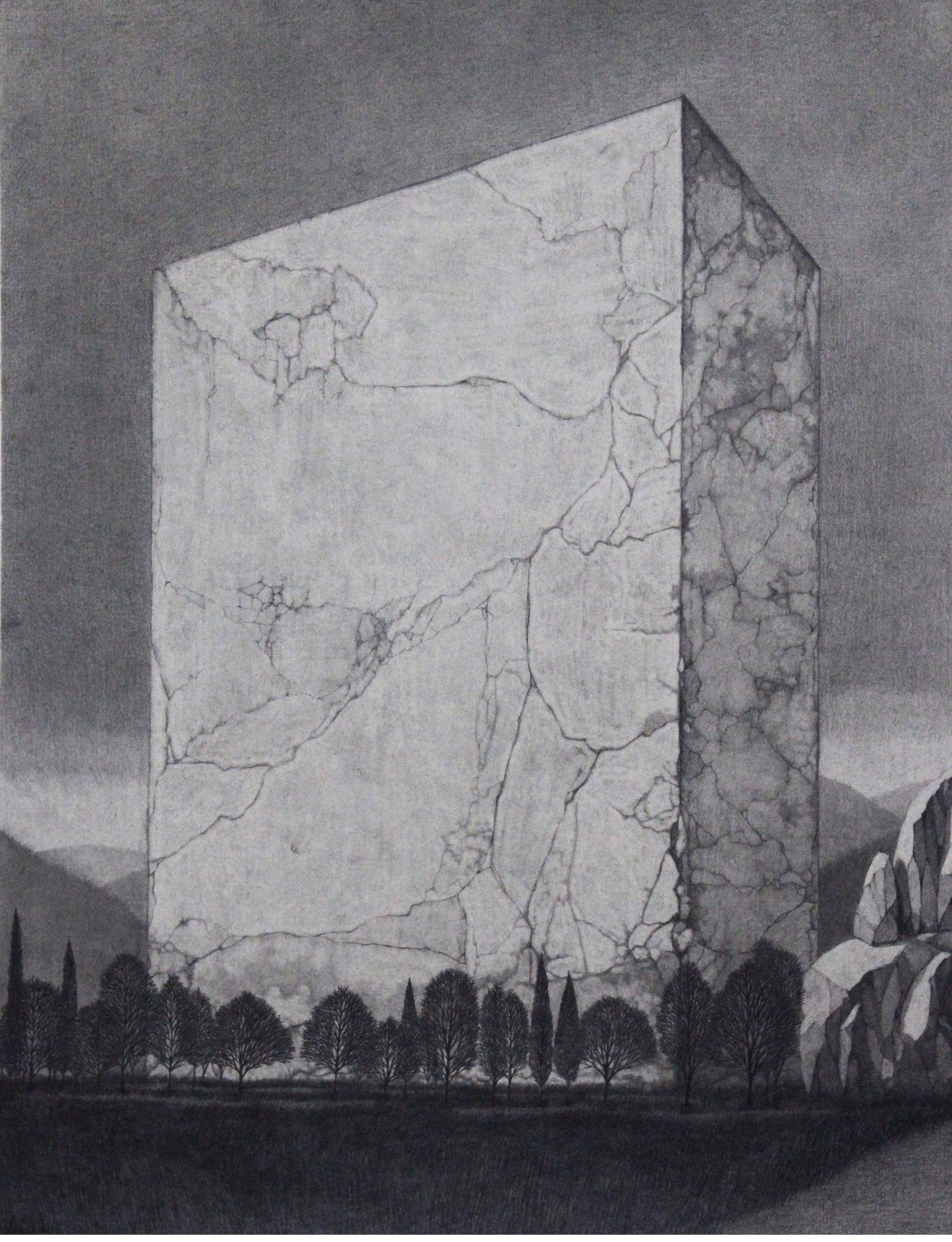

Partial collection of artworks submitted to the 2017 Behnam Bakhtiar Award competition