No language stays the same forever. The degree to which they change may vary, but a variety of factors – historical events, the introduction of new technologies, trade, immigration, human creativity, and the assimilation of “mistakes” – guarantee change in any language over time.

No stranger to this rule, the Persian language has changed significantly over time. Despite this, there have been many attempts to “purify” the language throughout history. Even today, movements exist to revert to earlier forms of Persian for ideological reasons.

In this article, I explore the idea of language purification by examining a contemporary movement called “Parsig” that seeks to revive Middle Persian, in the process removing the Arabic influences that have entered Modern Persian. Parsig echoes similar nationalist projects that have emerged occasionally over the last two centuries to “cleanse” Persian of “foreign” influences. But given the inevitable reality of language change and the impossibility of linguistic purity, what do efforts to “reform” Persian really serve to do?

Language and Power

The history of Persian is divided into three distinct periods: Old Persian, Middle Persian, and New Persian. Each refers to a broadly similar version of Persian distinct from the others (roughly similar to divisions between Old, Middle, and Modern English). Scholars believe that Old Persian may have existed between 500 and 300 BC, at which point the language we now call Middle Persian began to develop and flourish into the late 9th century AD. At that point, New Persian – the current Persian language – began to develop.

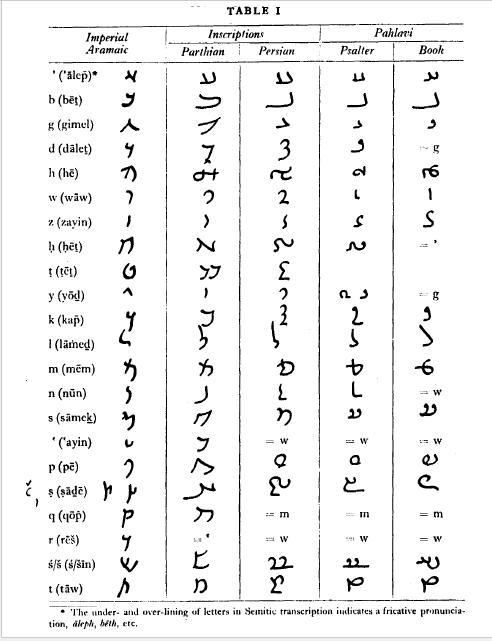

But these characterizations are over-simplifications. Texts from early New Persian – i.e. 1,000 years ago – are not easy to understand for modern-day speakers of New Persian. This is similar to how Shakespeare, despite being Modern English, can be difficult for English-speakers today to understand. By contrast, Old and Middle Persian are almost completely unintelligible to New Persian speakers. The debate continues over when and how to mark the different phases of the language, but perhaps the biggest shift from Middle Persian to Modern Persian is the introduction of the Arabic (rather than the Pahlavi) script.

Despite the fact that language changes over time, some are “maintained” through official bodies with institutional power, such as the Académie française which regulates French. Language regulation and standardization is often a key part of a nationalist identity, and is linked to the emergence of print and mass media, as scholars of nationalism like Benedict Anderson have argued. Even with this kind of regulation, however, spoken languages continue to change on a vernacular level as times change and speakers of the language change as well.

New Persian is today regulated formally by institutions in the three main countries in which the language is spoken. In Iran, there is the Academy of Persian Language and Literature, in Afghanistan the Academy of Sciences of Afghanistan and in Tajikistan, the State Language Committee.

“Reforming” Persian?

This kind of purposeful engagement with the language’s development is nothing new. Throughout history, Persian has seen its share of movements that sought radical changes. Many Persian speakers believe Ferdowsi’s Shahnama was an attempt to “purify” the Persian language (although scholars have put this idea in contention). Many prominent Persian language reformers appeared throughout the language’s history, particularly in 19th century and leading up until today.

One such 19th century reformer, Jalal Al-Din Mirza advocated for a “pure” Persian language to return to a pre-Islamic and pre-Arabized version of Iranian culture. His contemporary Mirza Fath Ali Akhundzade similarly advocated for a switch to Latin script for Persian. While Akhundzade’s attempt failed, in the 20th century in Tajikistan, Persian language switched to the Latin and then Cyrillic alphabets under Soviet rule. Today, Tajik Persian continues to be written with Cyrillic, while all others are written in the Perso-Arabic script. As a result, Tajik speakers of Persian are unable to read anything written in Tajik from before 1928, when the language switched. And although they can understand other variants of spoken Persian, they cannot read them.

In Iran in the 1920s, Reza Shah Pahlavi embarked on a project to replace foreign words that had entered Persian with local equivalents, many of which remain in use today. For example, the term foroodgah to replace the loan word aerodrom for an airport.

These efforts were met with criticism. Some critics claimed these attempts would be artificial rather than restorative, potentially damaging a language that had produced great works throughout history. Others noted that it was illogical to even focus on language reform at a time when illiteracy was still a major issue.

The Death and Life of Middle Persian

Tajik notwithstanding, few of these attempts were successful at radically changing modern Persian or accomplishing nationalist goals of “de-Arabization.” Despite this, such attempts continue even today.

Perhaps the most interesting and extreme example in our current period is Parsig.org: a movement to revive “Middle Persian” for colloquial use. It is primarily an online forum, though the website lists a 2011 conference as well. The Parsig revival movement has selected a form of the Middle Persian language, albeit with some simplifications, and seeks to revive it as a living language. As described on their website, the organization has online lessons and practice reading materials to encourage people to use Middle Persian in their daily life.

The following video is a clip from one of their conferences:

Parsig.org represents itself as a linguistic movement and social society. But a look at the website reveals its clear ideological goals. The group describes the end of Middle Persian as coming as a result of “Muslim fanaticism” and the “Arab-Muslim onslaught,” which Parsig argues “killed” a rich literary culture that seems to have been superior to whatever came later. These descriptions of the end of Middle Persian are informed by extreme nationalist views, prejudice toward Islam and the Arab world, and an oversimplified understanding of history in the service of nationalist ideology. By framing the story of the Persian language as such, Parsig encourages readers to mourn the loss of Middle Persian – and seek to avenge their past by reviving it.

This narrative of the Persian language is an unfortunate oversimplification. Middle Persian faded into New Persian with the Arab and Islamic conquests of the Sassanian (and Middle Persian speaking) world. After the sudden rupture of the Arab conquests of the Persian-speaking world at the time, the linguistic shift was a slow transition. Even though the use of labels to divide Middle and New Persian suggests a clean break between the two languages, in reality the development of the language was a gradual process. Early New Persian did not suddenly become unintelligible to speakers of New Persian, as the line itself is partly drawn due to the historical context. Ferdowsi’s Shahnama, for example, drew on previous histories to compose his work, some of which were Parthian language sources. Knowledge of Middle Persian continued to live on in linguistic studies, and also maintained scholarly and theological use by Zoroastrian Parsis in places such as India.

But by 9th and 10th century New Persian had already taken root as an important language, and started to help create what some consider the most precious literary heritage in the world: writers such as Ferdowsi, Khayyam, and Nizami had all completed their great works by the 11th century using the now Arabic-influenced New Persian language. These are just a few of the quintessential names the world considers greats of Persian culture and language. Centuries later, Persian speakers and fans of Persian culture have even more poets they continue to praise and enjoy.

Additionally, it was the Arab and later Turkic conquests that led to the Persian language being spread beyond its historical borders of use. This further enriched its language and literary history in places such as the Indian Subcontinent, where Persian was an official language for centuries at various levels of state and society.

Linguistic Hubris

Comments on the Parsig page from “supporters” reveal the true nature of the project’s idea of purity. One commenter writes, “Dear friends, I have done some pieces of works in reviving pure Persian (without Arabic loan words), and have written many poems in pure Persian. I strongly would like to purify and strengthen my language using the vocabulary and structure of Middle Persian (Parsig). When I read your website, I found that it is possible to revive Parsig: the language of a glorious civilization, the language of kings of the kings, the language of science and brotherhood!”

These comments reflect clearly that this supposedly linguistic project is about reviving a pre-Arabic version of Persian for ideological reasons, and not anything to do with New Persian’s comparative value as a language. As modern linguistics has demonstrated time and time again, if a language is being used by a community, it has the potential to be just as “good” or suitable for use as any other–languages exist to adapt. The idea of linguistic inferiority, that some languages are not as useful as others, is dismissed by the modern linguistic community.

In light of this, the Parsig revival movement appears to at its core be about a nostalgia for a time before Islam. This position is informed by the anti-Arab racism promoted by the Pahlavi regime that continues into the modern day, which emphasizes an exclusivist, racially-pure vision of Iran’s “Aryan” heritage that de-emphasized its diverse and cosmopolitan history and present. The position is also a common one among extreme nationalists opposed to the current Iranian government who consider the Iranian government’s religious policies in essence “Arabizing.”

This ideology often manifests in hateful ways. This is particularly troubling given the current state of white supremacist politics and violence, along with recent proof that even Iranians can be susceptible to supporting such ideologies.

Many languages that have been revived in recent history have been linked to a political project, such as the creation of a spoken Modern Hebrew – tied to the Zionist project in Palestine – or the ongoing revival of Hawaiian – tied to the islands’ autonomy and independence movements. In the case of the Parsig organization’s supporters, their political mission is clearly tied to the idea of historically and contemporarily taking revenge on the Muslim Arab civilization that conquered the region.

As it stands, Middle Persian as a language is indeed an interesting if under-supported realm of study. But, the group of revivalists at Parsig.org spend little time encouraging further study of current Middle Persian texts awaiting analysis. In fact, they neglect a lot of important original Middle Persian texts in the first place.

Instead, Parsig works to translate New Persian poems, such as Hafez and Khayyam, back into Middle Persian. These “backward translations” are bizarre from a linguistic perspective. Additionally, part of Persian poetry’s allure is the master the poets had of the aruz rhythmic and meter system. By eliminating Arabic-origin words–seemingly Parsig’s main goal–most poems would simply lose their meter, and of course their ability (through vocabulary) to draw on diverse themes from the eras in which they were written. Would this act of purifying masterworks of New Persian not actually muddy the meanings of these poems?

Contemporary Iranian attempts to “purify” their language or culture simply remind us of the anthropological axiom that reverting a culture to a past state is difficult or impossible, and instead such attempts often just create something new. To try to convert from New Persian to Middle Persian would not actually be a revolutionary act of turning back the clock, but would rather require the creation of a new configuration of Iranian culture: one in which the history of the mixing of the past millennium of history across Iran, Central Asia, the Middle East, and the Indian Subcontinent has been erased.

One cannot deny that foreign linguistic influences have shaped the Persian language from antiquity until the present. If someone wants to remove Arabic influence from Persian, why not also remove the even older Aramaic or Parthian influence on Middle Persian? The ridiculousness of this obsession with purity is is obvious if one considers that Middle Persian was anyways originally Old Persian, and shifted due to many other factors. Isn’t the obsession with Middle Persian itself arbitrary?

Rejecting the linguistic reality that contemporary Persianate culture rests upon would make the modern language opaque and inaccessible. Trying to strip modern Persian of its many layers of developments and external linguistic influences is an unnecessary act of self-destruction. Perhaps most stunningly, it is an act of hubris: if the language was good enough for the great masters of Persian poetry, surely it is good enough for us.