At the height of this winter’s protest movement in Iran, there was a temporary ban on the Telegram messaging app, alongside the other popular foreign social media platform, Instagram. This lasted from 30 December 2017 to 13 January 2018.

Although temporary, the ban had big implications in Iran, where the IP-based messaging app is immensely popular. Telegram dominates the messaging app market inside of Iran and is seen as the central (private and public) communication platform for Iranians.

Out of a total population of 80 million people, 50 million Iranians have Internet access, and among those users, 45 million are on Telegram. Telegram’s public channels boast a wide array of topics, both political and quotidian, some of which are opposition diaspora channels, which ordinarily would be censored on other platforms.

While the temporary ban was widely acknowledged, new evidence indicates that the government throttled or slowed connection speeds to the platform in the days after it lifted the block on the platform. This adds a new layer of concern to the issue of Iran’s attempts to control and tighten the net.

The ban on telegram — and indications of throttling — cast doubt on the discourse of opening up the internet that the administration of President Hassan Rouhani had promised to improve. One of the greatest achievements of the Rouhani administration in promoting Internet freedom has been their success at keeping platforms like Instagram and Telegram uncensored against efforts of the more conservative and hardline elements of leadership in the country. But efforts by the Rouhani administration to re-open platforms such as Twitter that have been blocked since 2009 seem more unlikely after the events surrounding Telegram.

The decision to block Telegram was a violation of due process and the rule of law, imposed by various security agencies within the country working outside the bounds of official law and associated protocols.

According to provisions of the Computer Crimes Law and the multi-agency body of the Supreme Council of Cyberspace, multiple authorities should review and approve such decisions before they are acted upon. Statements by Minister of Information Communication and Technology Mohammad Javad Azari Jahromi later indicated the decisions were made by the Supreme National Security Council.

Once the block on Telegram was removed on 13 January 2018, users reported slow connections over the application. Telegram founder and CEO Pavel Durov confirmed this to be the case on the platform in a 15 January 2018 tweet:

The reports that @telegram has been unblocked in Iran are consistent with our data, however, the speed of access to @telegram in Iran hasn't reached its pre-blocking level. We are analyzing the traffic to understand the reason for this before making any announcements.

— Pavel Durov (@durov) January 15, 2018

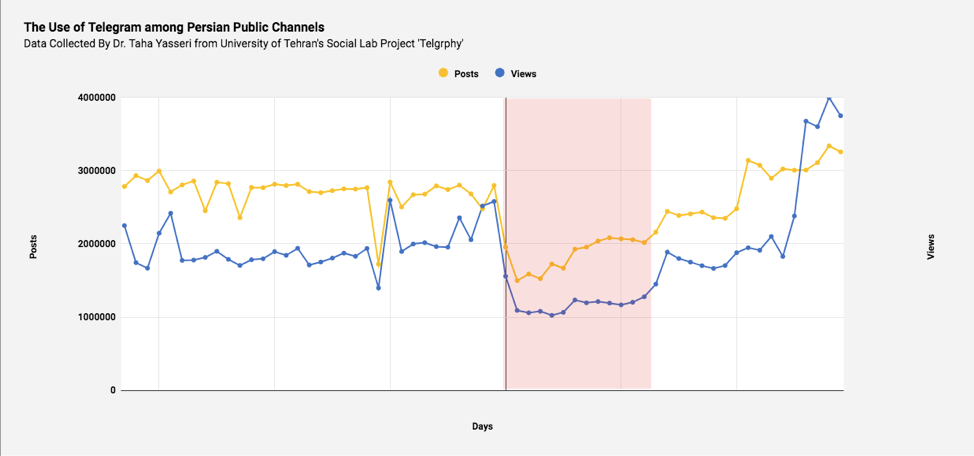

Data from the University of Tehran’s social lab demonstrated that the number of posts on Persian public channels and the number of views on these posts struggled to return to the same levels after the block was removed (the pink area is the period of blockage). Levels only returned to previous numbers around 20 January 2018.

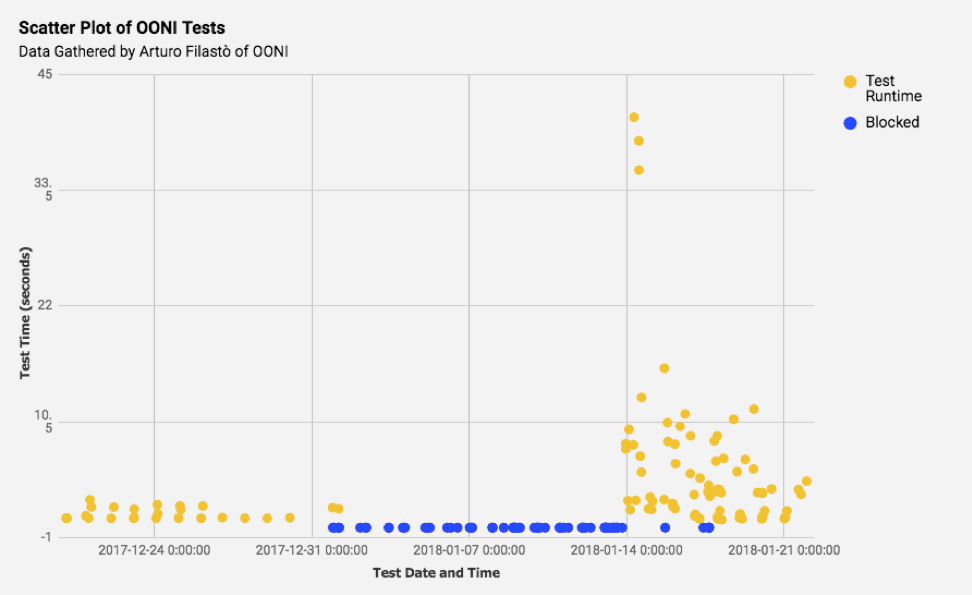

Test results from the Open Observatory of Network Interference (OONI), an initiative that uses remote probes to test for technical internet censorship around the world, showed a slow return on test times when they probed for censorship results from the Telegram app and web version within Iran.

Telegram itself has released no data about activity in Iran since Durov’s 15 January 2018 statement, in keeping with its characteristic lack of transparency in documenting government interference with its platform.

The data from the University of Tehran and the OONI probes are not exact science. But when combined with anecdotal user reports, they give a strong indication that authorities were continuing to limit the application’s use after the ban was lifted, in further violation of internet access obligations that the Rouhani administration has pledged to meet, both at the national and international levels.

The government itself has made no official statements on whether or not it is throttling connections. Many users were still reporting that slow download speeds were posing hurdles to their business dealings. On 17 January 2018, Minister Jahromi tweeted that he was meeting with the Supreme Council for Cyberspace to coordinate their policy on digital economy, in the wake of the effects of filtering on businesses. Users started to question the Ministry’s role in the slow download speeds, but got no response from the typically vocal Minister.

Given this evidence, it would behoove Iran’s Ministry of ICT, a institution part of the elected Rouhani administration, in place to represent the concerns of the Iranian people, to transparently document the means and extent at efforts to control online communication.

Furthermore, Telegram has not responded to how their infrastructure inside of the country was affected while the government implemented a ban on the platform. In July 2017, the company moved its Content Delivery Networks (CDNs) into Iran and began hosting public media on the platform’s channel on servers inside of the country, in order to increase download speeds. Iranians would also be better served by Telegram if the company released any data bearing evidence of government disruptions or other types of interference in their service from January 15.

While Telegram is now accessible, both the government and the company should place mechanisms of accountability and process in place to ensure that access to information — regardless of politics or company policy — is a guarantee for Iranians, regardless of politics.

Via Article19