In recent months a string of school shootings in the United States has rekindled the debate over gun violence, its causes and what can be done to stop it. But amid endless talk of school shootings and AR-15s, a large piece of the puzzle has been left conspicuously absent from the debate.

Contrary to the notion that mass murderers are at the heart of America’s gun violence problem, data from recent years reveals that the majority of gun deaths are self-inflicted.

In 2015, suicides accounted for over 60 percent of gun deaths in the U.S., while homicides made up around 36 percent of that year’s total. Guns are consistently the most common method by which people take their own lives.

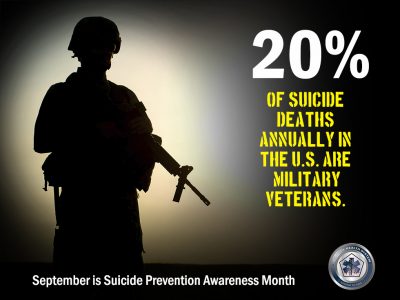

While the causes of America’s suicide-driven gun epidemic are complex and myriad, it’s clear that one group contributes to the statistics above all others: military veterans.

Beyond the Physical

According to a 2016 study conducted by the Department of Veterans Affairs, on average some 20 veterans commit suicide every single day, making them among the most prone to take their own lives compared to people working in other professions. Though they comprise under 9 percent of the American population, veterans accounted for 18 percent of suicides in the U.S. in 2014.

When veterans return home from chaotic war zones, resuming normal civilian life can present major difficulties. The stresses of wartime create a long-term, sustained “fight-or-flight” response, not only producing physical symptoms such as sweating, shaking or a racing heart rate, but inflicting a mental and moral toll as well.

Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) accounts for some of the physiological effects of trauma, the “fight-or-flight” response, but the distinct mental, moral and spiritual anguish experienced by many veterans and other victims of trauma has been termed “moral injury.”

A better understanding of that concept and the self-harm it motivates could go a long way toward explaining, and ultimately solving, America’s suicide epidemic.

“Moral injury looks beyond the physical and asks who we are as people,” Peter Van Buren, a former State Department Foreign Service officer, said in an interview. “It says that we know right from wrong, and that when we violate right and wrong, we injure ourselves. We leave a scar on ourselves, the same as if we poked ourselves with a knife.”

While not a veteran himself, during his tenure with the Foreign Service Van Buren served for one year alongside American soldiers at a forward operating base in Iraq. His experiences there would stick with him for life.

“Over the course of the year I was there, the units I was embedded with lost three men, and all of them were lost to suicide, not to enemy action,” Van Buren said. “This left an extraordinary impression on me, and triggered in me some of the things that I write about.”

After retiring from the Foreign Service, Van Buren began research for his novel “Hooper’s War,” a fictional account set in WWII Japan. The book centers on American veteran, Nate Hooper, and explores the psychological costs paid by those who survive a war. Van Buren said if he set the book in the past, he thought he could better explore the subject matter without the baggage of current-day politics.

In his research, Van Buren interviewed Japanese civilians who were children at the time of the conflict and found surprising parallels with the soldiers he served with in Iraq. Post-war guilt, he found, does not only afflict the combatants who fight and carry out grisly acts of violence, but civilians caught in the crossfire as well.

For many, merely living through a conflict when others did not is cause for significant distress, a condition known as “survivor’s guilt.”

“In talking with them I heard so many echoes of what I’d heard from the soldiers in Iraq, and so many echoes of what I felt myself, this profound sense of guilt,” Van Buren said.

‘We Killed Them’

Whether it was something a soldier did, saw or failed to prevent, feelings of guilt can leave a permanent mark on veterans after they come home.

Brian Ellison, a combat veteran who served under the National Guard in Iraq in 2004, said he’s still troubled by his wartime experiences.

Stationed at a small, under protected maintenance garage in the town of ad-Diwaniyah in a southeastern province of Iraq, Ellison said his unit was attacked on a daily basis.

“From the day we got there, we would get attacked every night like clockwork—mortars, RPGs,” Ellison said. “We had no protection; we had no weapons systems on the base.”

On one night in April of 2004, after a successful mission to obtain ammunition for the base’s few heavy weapons, Ellison’s unit was ready to hit back.

“So we got some rounds for the Mark 19 [a belt-fed automatic grenade launcher] and we basically used it as field artillery, shot it up in the air and lobbed it in,” Ellison said. “Finally on the last night we were able to get them to stop shooting, but that was because we killed 5 of them. At the time this was something I was proud of. We were like ‘We got them, we got our revenge.’”

“In retrospect, it’s like here’s this foreign army, and we’re in their neighborhood,” Ellison said. “They’re defending their neighborhood, but they’re the bad guys and we’re the good guys, and we killed them. I think about stuff like that a lot.”

Despite his guilt, Ellison said he was able to sort through the negative feelings by speaking openly and honestly about his experiences and actions. Some veterans have a harder time, however, including one of Ellison’s closest friends.

“He ended up going overseas like five times,” Ellison said. “Now he’s retired and he can’t even deal with people. He can’t deal with people, it’s sad. He was this funny guy, everybody’s friend, easy to get along with, now he’s a recluse. It’s really weird to see somebody like that. He had three young kids and a happy personality, now he’s broken.”

In addition to the problems created in their personal relationships, the morally injured also often turn to self-destructive habits to cope with their despair.

“In the process of trying to shut this sound off in your head—this voice of conscience—many people turn to drugs and alcohol as a way of shutting that voice up, at least temporarily,” Van Buren said. “You hope at some point it shuts up permanently . . . Unfortunately, I think that many people do look for the permanent silence of suicide as a way of escaping these feelings.”

A Hero’s Welcome?

By now most are familiar with the practice of celebrating veterans as heroes upon their return from war, but few realize what psychological consequences such apparently benevolent gestures can have.

“I think the healthiest thing a vet can do is to come to terms with reality,” Ellison said. “It’s so easy to get swept up—when we came home off the plane, there was a crowd of people cheering for us. I just remember feeling dirty. I felt like ‘I don’t want you to cheer for us,’ but at the same time it’s comforting. It’s a weird dynamic. Like, I could just put this horror out of my mind and pretend we were heroes.”

“But the terrible part is that, behind that there’s reality,” Ellison said. “Behind that, we know what we were doing; we know that we weren’t fighting for freedom. So when somebody clings onto this ‘we were heroes’ thing, I think that’s bad for them. They have to be struggling with it internally. I really believe that’s one of the biggest things that contributes to people committing suicide. They’re not able to talk about it, not able to bring it to the forefront and come to terms with it.”

Unclear Solution

According to the 2016 VA study, 70 percent of veterans who commit suicide are not regular users of VA services.

The Department of Veteran Affairs was set up in 1930 to handle medical care, benefits and burials for veterans, but some 87 years later, the department is plagued by scandal and mismanagement. Long wait times, common to many government-managed healthcare systems, discourage veterans from seeking the department’s assistance, especially those with urgent psychiatric needs.

An independent review was carried out in 2014 by the VA’s Inspector General, Richard Griffin, which found that at one Arizona VA facility, 1,700 veterans were on wait lists, waiting an average of 115 days before getting an initial appointment.

“People don’t generally seek medical help because the [VA] system is so inefficient and ineffective; everyone feels like it’s a waste of time,” said a retired senior non-commissioned officer in the Special Operations Forces (SOF) who wished to remain anonymous.

“The system is so bad, even within the SOF world where I work, that I avoid going at all costs,” the retired officer said. “I try to get my guys to civilian hospitals so that they can get quality healthcare instead of military healthcare.”

Beyond institutions, however, both Ellison and Van Buren agreed that speaking openly about their experiences has been a major step on their road back to normalcy. Open dialogue, then, is not only one way for veterans and other victims of trauma to heal, it may ultimately be the key to solving America’s epidemic of gun violence.

The factors contributing to mass murders, school shootings and private crime are, no doubt, important to study, but so long as suicide is left out of the public discourse on guns, genuine solutions may always be just out of reach.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=puAJcGfIq7U&feature=youtu.be

Via Consortium News