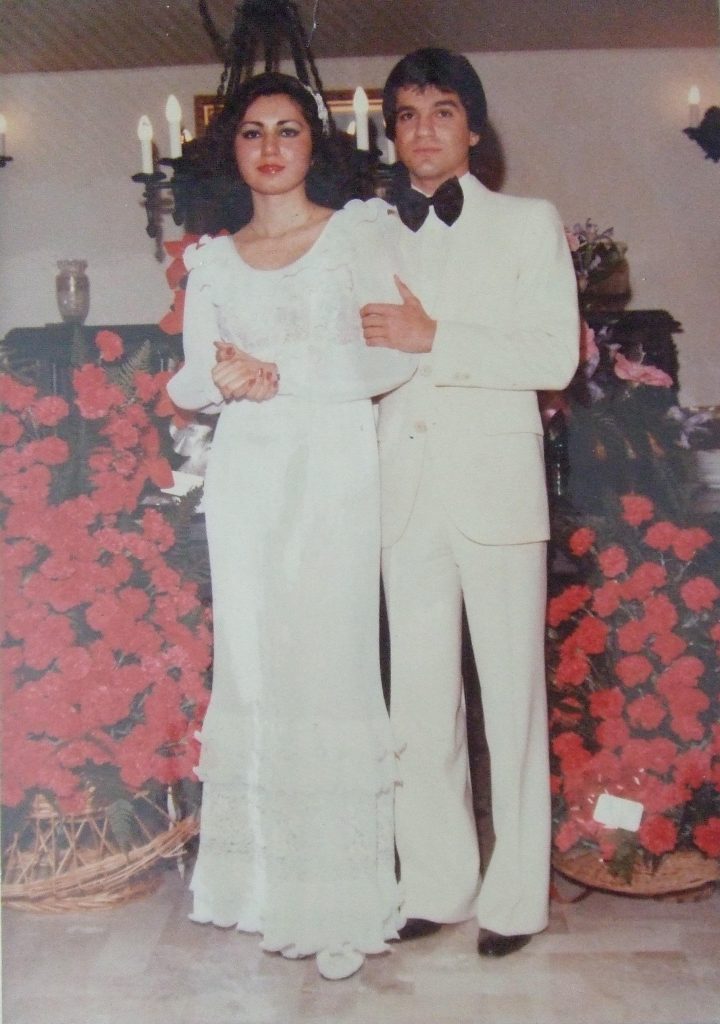

Forty years ago in 1978, my parents decided to get hitched in Iran. Dad had met Mum — then only seventeen — in the States when they were both studying at the University of Portland, and, after only a month or so, popped the question. Not having many friends or relatives in the States, they thought it would be a better idea if they instead travelled back home during Christmas break. Under ordinary circumstances, it would have been; but the Iran they were going back to wasn’t the one they’d left some years earlier. Celebrations of all kinds had been banned. There were riots in the streets, martial law in force, and pyromaniacs on the loose. The Iranian Revolution — one of the most momentous events of the twentieth century — was in full swing.

For as long as I can remember, my parents have been recounting the tragicomic story of their tumultuous marriage to guests around the dinner table. As a child, I used to relish listening to Mum and Dad’s anecdotes, which then seemed like something out of an adventure novel, and would sit, spellbound, as they fended off fits of laughter one moment, only to turn bleary-eyed the next. Never could I, wide-eyed and full of wonder, have imagined then the ways in which my parents’ marriage would affect my own views on relationships. And, while US-Iran relations certainly weren’t anything to write home about, even as a kid in the nineties, we all thought the worst had passed. Today, largely thanks to President Trump’s foreign policies, the rift between the two countries seems to be just as wide as it was forty years ago at the start of the Revolution, if not wider.

My parents didn’t have a fancy marriage, by any stretch of the imagination. It wasn’t even what you’d consider modest. As everyone was on strike, they couldn’t find a venue to hold the reception in, and instead had to use an empty flat in a building owned by Mum’s parents. Only sixty people or so could attend, meaning even some of my parents’ closest friends and relatives couldn’t be with them. Because of the curfew in place, most of their guests left before sundown; and, with there being a shortage of just about everything in the country, a tank of gas someone gave them was amongst their most memorable gifts. They used it to drive to the Hyatt in Tehran, which was all but abandoned. They left after spending just one night there, and woke up the following morning to find that their car had been broken into, and all their presents and clothes stolen.

But none of these things mattered to them in the slightest. They were too much in love to care about such luxuries as weddings and honeymoons, and least of all about being caught in the flashpoint of the Revolution. Mum also happened to be going through a pseudo-leftist phase in which she thought she only needed one pair of jeans in life, which probably explains why she bought the second dress she hastily tried on (before the store was set on fire for not obeying Khomeini’s call for a strike), and didn’t even bother trying on the shoes passed to her from beneath a timid proprietor’s metal curtain. What came as a surprise to everyone, however — including she herself — was that, prior to meeting Dad, she’d been staunchly anti-marriage. When he came into the picture, though, she underwent her own sort of revolution.

They were too much in love to care about such luxuries as weddings and honeymoons, and least of all about being caught in the flashpoint of the Revolution.

Dad was a different story. Being twenty-five — eight years older than Mum — he’d naturally seen more of the world, and even at that age had wanted to settle down. He was tired of dating, and had even rejected the proposal of an American girl who’d fallen for him. That’s why, the minute he knew he’d struck gold with Mum, he rang her up on the telephone to ask her ‘a very important question’. True, he could have been a bit more smooth, but you get the idea.

When recalling those heady days, during which Dad defiantly drove through walls of flaming tires set up in protest, and Mum nearly got torched by one of Khomeini’s devotees, they both admit that they were foolhardy and unbelievably lucky. Yet, while they looked at the Revolution as fun and games (at least, until reality slapped them back in the States), they were dead serious about their commitment to one another. From the moment Dad proposed over the phone, they encountered no shortage of obstacles. The Revolution aside, Mum’s parents were against the whole idea, especially as she was only seventeen, and Grandma suspected Dad of being a junkie (as she did all Iranian students abroad). Back in the States, during the Hostage Crisis of 1979, they were branded illegal aliens by an immigration officer in cowboy boots who rubbed his hands with glee as he did so. They ended up leaving after their studies to work in an Iran then being invaded by Saddam Hussein, and, after having me, gave up everything to immigrate to Canada not only in the dead of winter, but in the midst of a recession, too. Not for a minute, however, did they let a single one of their fears, doubts, or, at times, nightmares, come between them.

To get back to me — my parents, particularly in the past few years, have been the biggest influence on my outlook towards relationships and the idea of marriage. As a teenager, I, like Mum, used to roll my eyes whenever there’d be talk of my settling down one day. While I did find the story of how she and Dad met sweet, I thought — as teenagers usually do — that I was an exception to the rule, and that I’d be more steadfast in my rejection of marriage than Mum had been. It was also hard to stomach the fact that Dad had proposed after only dating for a month. Hell, I spent more time thinking about which guitars and records I wanted to buy. As such, I couldn’t help but eat humble pie when, after having only known a girl for some months at the age of twenty-four, I got down on bended knee and asked her to be mine. Looking back now, six years on, it’s clear to me that, like Mum, I wasn’t really anti-marriage at all, and had just been waiting for the right person to come along, and how, like Dad, I was a helpless romantic who’d also quickly tired of the ‘scene’.

That I called the whole thing off a year later only further illustrates the extent of my parents’ influence on me. True, my fiancée’s dream of having an extravagant fairytale wedding was in stark contrast to my idea of just getting together with our folks for a few bottles of champagne — but that’s not why I told her I had to let her go over dinner one evening. Dad’s words were ping-ponging in my mind more forcefully than ever during those final days of our relationship, in which I tried my utmost to salvage what I, at least, knew was beyond repair. ‘The moment we got married’, he’d told me on more than one occasion, ‘that was it.’ Suffice it to say, ‘divorce’ wasn’t a word in Dad’s vocabulary. After taking a long, hard look at our relationship and our differences, I confessed that, despite having had the best of intentions when I’d proposed, I didn’t have enough faith in us to make a lifelong commitment. Do we love each other enough to endure what Mum and Dad had? I asked myself. The answer was a resounding no.

This December — New Year’s Eve, to be precise — my parents will celebrate the fortieth anniversary of their marriage during the apex of the Iranian Revolution. Much has changed since that turbulent time, and much hasn’t. Although they lost everything shortly after coming to Canada, Mum is now one of the country’s most accomplished and well-known financial advisers, and Dad, although an engineer and architect by profession, an independent management consultant. And, just as US-Iran relations are seemingly stuck in 1979, so too are my parents, in their heart of hearts. ‘You’ll always be twenty-five to me’, Mum recently told Dad on his sixty-fifth birthday.

Having just ended another relationship, I’ve had my fill for the moment and haven’t exactly thinking about marriage recently. But, sitting here writing about Mum and Dad now, and imagining the looks in their eyes as they burst open that bottle of champagne on New Year’s Eve, I dare say I’m more than tempted to throw myself in the thick of things again. I might not be able to remain twenty-five in my sweetheart’s eyes forever, but I suppose thirty isn’t so bad.