The murder of Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi at Saudi Arabia’s consulate in Istanbul has put the United States’ relationship with the wealthy Gulf power under intense scrutiny.

After weeks of denying any knowledge about Khashoggi’s fate, Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman now says that Saudi agents strangled Khashoggi after a fistfight. Eighteen men have been arrested.

The Khashoggi affair highlights a persistent oddity in American foreign policy, one I observed in many years working at the State Department and Department of Defense: selective morality in dealing with repressive regimes.

A panoply of dictators

President Donald Trump praised the arrests as “good first steps” in the case, despite Turkey’s claim to have audio and video evidence that the Saudis tortured, assassinated and dismembered Khashoggi. Many of those arrested have close links to Salman.

Trump’s reluctance to confront Saudi Arabia over the killing of Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist who lived in the U.S., has spurred global outrage.

He and other White House officials have reminded critics that Saudi Arabia buys billions of dollars in weapons from the U.S. and is a crucial partner in the American pressure campaign on Iran.

The comment highlights why the U.S. has for decades maintained close ties with some of the world’s worst human rights abusers.

Ever since the country emerged from the Cold War as the world’s dominant military and economic power, consecutive American presidents have seen financial and geopolitical benefit in overlooking the bad deeds of brutal regimes.

Changing allegiances in the Middle East

Before the Islamic revolution in 1979, Iran was a close U.S. ally. Shah Reza Pahlavi ruled harshly, using his secret police to torture and murder political dissidents.

But the shah was also a secular, anti-communist leader in a Muslim-dominated region. President Nixon hoped that Iran would be the “Western policeman in the Persian Gulf.”

After the Shah’s overthrow, the Reagan administration in the 1980s became friendly with Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein. The U.S. supported him with intelligence during Iraq’s war with Iran and looked the other way at his use of chemical weapons.

And before Syria’s intense, bloody civil war – which has killed an estimated 400,000 people and featured grisly chemical weapon attacks by the government – its authoritarian regime enjoyed relatively friendly relations with the U.S.

Syria has been on the State Department’s list of state sponsors of terrorism since 1979. But presidents Nixon, Jimmy Carter, George H.W. Bush and Bill Clinton all visited President Bashar al-Assad’s father, who ruled from 1971 until his death in 2000.

Why Saudi Arabia matters

The alleged assassination of Khashoggi by Saudi operatives may seem surprising because of the 31-year-old crown prince’s reputation as a moderate reformer.

Salman has made newsworthy changes in the conservative Arab kingdom, allowing women to drive, combating corruption and curtailing some powers of the religious police.

Still, Saudi Arabia remains one of the world’s most authoritarian regimes.

Women must have the consent of a male guardian to enroll in college, look for a job or travel. They cannot swim in public or try on clothes when shopping.

The Saudi government also routinely arrests people without judicial review, according to Human Rights Watch. Citizens can be executed for nonviolent drug crimes, often in public. Forty-eight people were beheaded in the first four months of 2018 alone.

Saudi Arabia ranks just above North Korea on political rights, civil liberties and other measures of freedom, according to the democracy watchdog Freedom House.

But its wealth, strategic Middle East location and petroleum exports keep the Saudis as a vital U.S. ally.

President Obama visited Saudi Arabia more than any other American president – four times in eight years – to discuss everything from Iran to oil production.

American realpolitik

This kind of foreign policy – one based on practical, self-interested principles rather than moral or ideological concerns – is called “realpolitik.”

Henry Kissinger, secretary of state under Nixon, was a master of realpolitik, which drove that administration to normalize its relationship with China. Diplomatic relations between the two countries had ended in 1949 when Chinese communist revolutionaries took power.

Then, as now, China was incredibly repressive. Only 17 countries – including Saudi Arabia – are less free than China, according to Freedom House.

But China is also the world’s most populous nation and a nuclear power. Nixon, a fervent anti-communist, sought to exploit a growing rift between China and the Soviet Union.

Today Washington retains the important, if occasionally rocky, relationship Kissinger forged with Beijing. President Trump may be critical of Chinese trade practices, but he is largely silent on China’s ongoing persecution of Muslim minority groups.

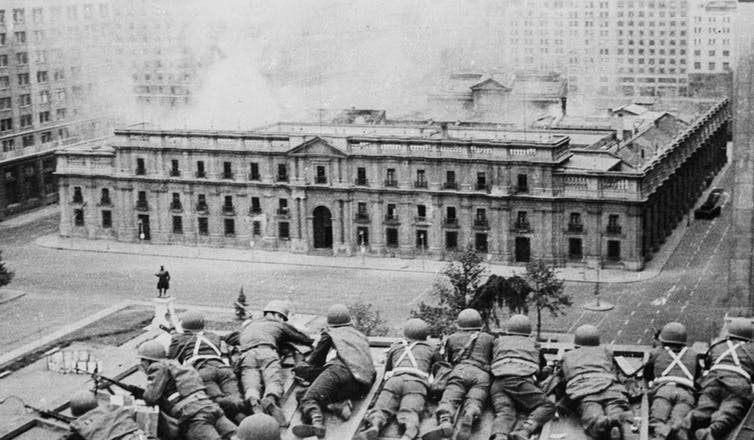

American realpolitik is not limited to the Mideast. After the Cuban Revolution of 1959, the U.S. regularly backed Latin American military dictators who tortured and killed citizens to “defend” the Americas from communism.

US not ‘so innocent’

U.S. presidents tend to underplay their relationships with repressive regimes, lauding lofty “American values” instead.

That’s the language former President Barack Obama used in September to criticize Trump’s embrace of Russia’s authoritarian president, Vladimir Putin, citing America’s “commitment to certain values and principles like the rule of law and human rights and democracy.”

But Trump defended his relationship with Russia, tacitly invoking American realpolitik. “You think our country’s so innocent?” he asked on Fox News.

I can’t say he’s wrong.

The U.S. maintains close ties to numerous regimes whose values and policies conflict with America’s constitutional guarantees of democracy, freedom of speech, the right to due process and many others.

It has for decades.

Saudi Arabia’s brutal treatment of journalist Jamal Khashoggi is causing international outcry and hand-wringing within the U.S. government.

But American realpolitik suggests the tight U.S.-Saudi relationship will continue.

Via The Conversation