These days a lot of us hyphenated Iranians have been going down the memory lane to make sense of the euphoria, mania or what-have-you that gripped the Iranian nation back in the late 70s only to ultimately erupt in the form of a cataclysmic event, a revolution. A fortieth birthday of a human being is a milestone event as it is viewed as the second coming-of-age of a person. While the first coming-of-age is mostly witnessed in the youth who are about to transition into adulthood, the second coming-of-age is that which has become associated with ripeness, wisdom and even prophethood as is evident in the ordainment of Prophet Muhammad at the age of forty. The number “forty” has taken on further portentous layers including in the Deluge which lasted forty days as well as in records that suggest that Moses spent forty days on Mount Sinai where the ten commandments were revealed to him.

In literature, the number comes to the fore, for example, in Kafka’s “Hunger Artist” (“Hungerkünstler,” 1922), a limit of forty days has been imposed on the fasting artist who in finding it restrictive, despises it. Of course, what the hunger artist also imparts to us is of great import as he asserts the reason to his fasting as being rooted in the fact that he could not find the food that he liked. He goes on to say: “Had I found it, trust me, I would have not made a scene and stuffed myself like you and everyone else.” The food metaphor becomes valuable with regard to the longest serving prime minister in Iran, Amir Abbas Hoveyda’s fondness for André Gide’s Fruits of the Earth (Nourritures Terrestres, 1897). Hoveyda’s attachment to Gide’s so-called “prose-poem” stands in contradistinction to the express stipulates of the text itself which admonishes against holding on to its contents . Yet, this Iranian “chief of staff,” as he described himself, seemed to have enacted parts of the text that bid the character Nathanaël, and by extension us readers, to explore the world in ways that would allow aspects of us to flourish that render us unique, different from the rest of our race.

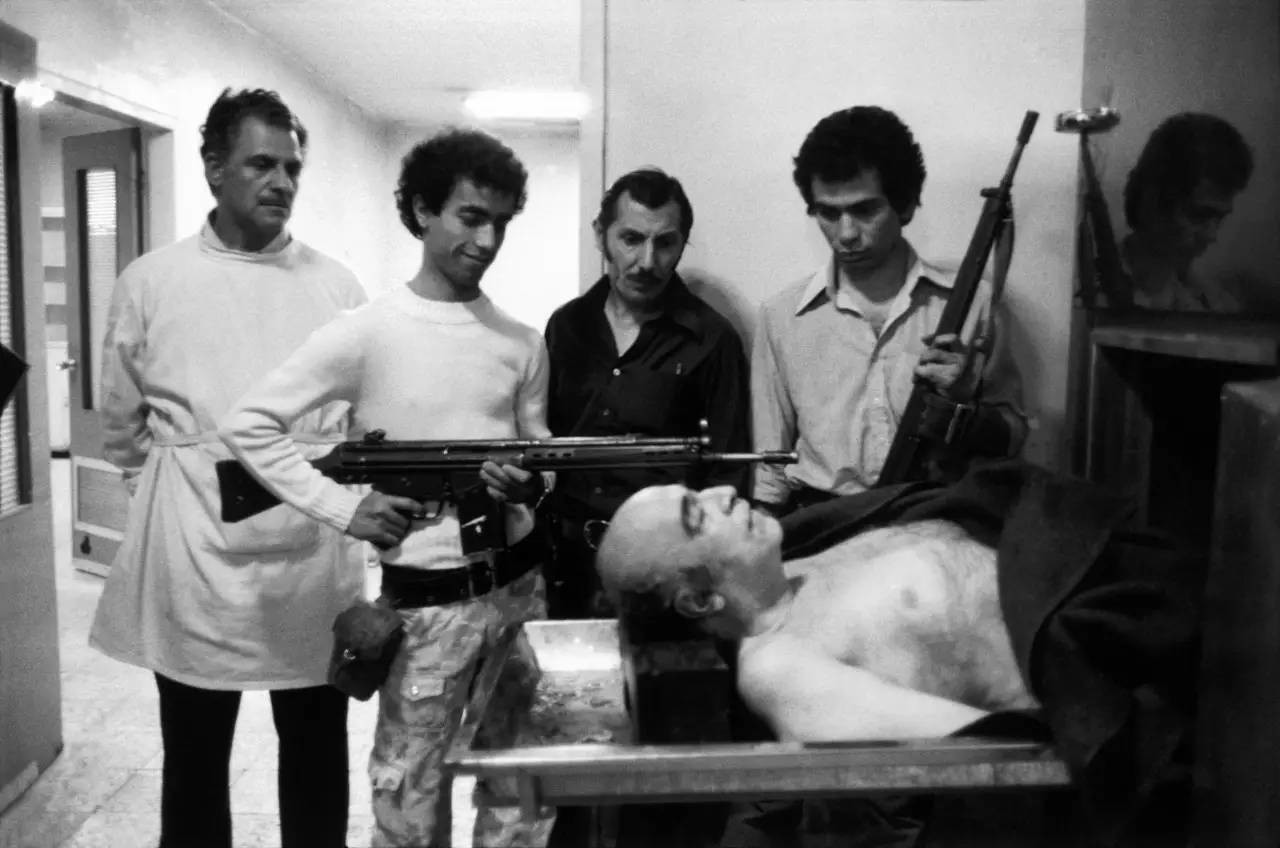

As I was watching Hoveyda’s final moments, I could not help but wonder how he could have been accused of “spreading corruption on earth.” After all, such a label does not stick to a lover of literature.

There is a scene in the acclaimed movie The Lives of Others (Das Leben der Anderen, 2006) where the seemingly impregnable Stasi officer, Gerd Wiesler who has been entrusted with the task of spying on the playwright Georg Dreyman softens by the poetry that imbues the lives of those he was spying upon. The thralldom is such that he sneaks into Dreyman’s apartment to steal a volume of Bertolt Brecht’s poetry:

And above us in the beautiful summer sky, was a cloud/ which I looked at for long/It was very white and way above/ and when I looked up, it was no more…

Not everyone is capable of deriving pleasure from the configuration of the clouds in the firmament, let alone from the poetry that sees the light of day in the wake of such intense moments of ferveur, as Gide’s narrator in Les Nourritures Terrestres would have it.

Hoveyda, in his ability to appreciate literature, manifests a ferveur that goes beyond the sonority of words to that of the Word writ large in the sense of the élan vital that lies at the beginning of every act of creation. In The Lives of Others we see how by and by, Wiesler turns into one of those whom Dreyman had referred to as “those who really listen to Beethoven’s music can never be bad.” Hoveyda did not need that conversion, his life-long experience across the world in actual geographical and imaginatively poetic terms, had already rendered him a connoisseur of lexical and technical tours de force.

That having been said, it goes without saying that like every human being, he bore certain foibles that were, in part, rooted in his passion for poetry and fervent francophilia. An example in point is the naiveté that he manifests, in his final interview in Qasr Prison with the Belgian journalist, Christine Ockrent, as he insists that it is premature to use the term “victim” in his case, suggesting that his trial may prove otherwise. Yet, one cannot but admire the poise that he demonstrates in his responses to the annoyingly pushy Ockrent while awaiting a verdict that would prove to be the exact opposite of what he had been hoping for. It is also ironic that he rejects the offer of an ambassadorship to Belgium in the dying days of the Pahlavi regime on grounds that he had committed no wrong.

While on a micro-level this article seems to bear traces of an hommage to Iran’s longest serving prime minister, on a macro-level, it seeks to shed light on an example of how a sense of befuddlement had set in following the revolution. Scenes from Hoveyda’s trial go on to hint at a naiveté that should have long been effaced in the span of the life of a seasoned politician. One is also reminded of Adolf Eichmann and his invocation of Kant’s “categorical imperative,” on whose basis, one is to act by a maxim that one wishes to turn into a universal law. Hoveyda, though in no way evil as the top SS officer, sounds, similarly, befuddled by all the poetic peregrinations of his mind at his trial, expresses exasperation at not being viewed as a mere cog in a machine. The die has already been cast without a thorough substantiation of the litany of allegations leveled against him. It takes him a long while to see the writing on the wall and the futility of the “fruits of the earth” in such a peripetian period of history.

The “Persian Sphinx,” an epithet Abbas Milani uses to describe him, seems à propos.

The “Persian Sphinx,” an epithet Abbas Milani uses to describe him, seems à propos. He was, definitely, a multi-faceted character and while hints of his complicity in the imprisonment of those held accountable under the Shah by Ockrent seem to hold no water (though he ought to have, perhaps, equipped himself with more knowledge as to what had been going on during his tenure in the underbelly of the apparatus), his downfall can be traced back to the parochial perspective that accompanies the life of an intellectual who errs in assuming those around him to be weighing their words and actions in a manner similar to his own. The “fruits of the earth,” which based on Rousseau’s maxim, belongs to everyone, these days, conjure up a sector of the society who get to enjoy the means afforded by a wealth that should have been distributed across the entire the nation, at the cost of a placing a large collective between the rock of the US-led sanctions and the hard place of a system that does little to better their living conditions, let alone improve their overall prospects with little in sight of a second coming-of-age.

Cover photo: Crown Prince Reza Pahlavi with Amir Abbas Hoveyda and Asadollah Alam.