Veyron Pax always knew art was his calling but had a difficult time earning acceptance as a gay artist in his Iranian Kurdish hometown of Kermanshah. The 27-year old has had no such problem winning recognition in the United States however, for creating digital art that contrasts his life in Iran with his U.S. immigrant experience.

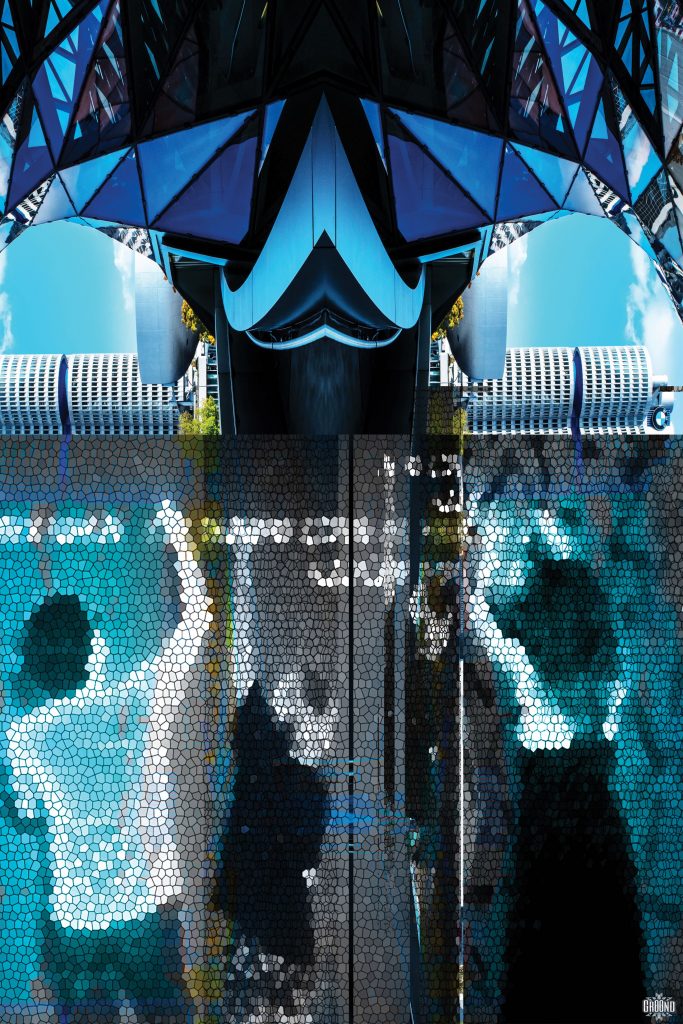

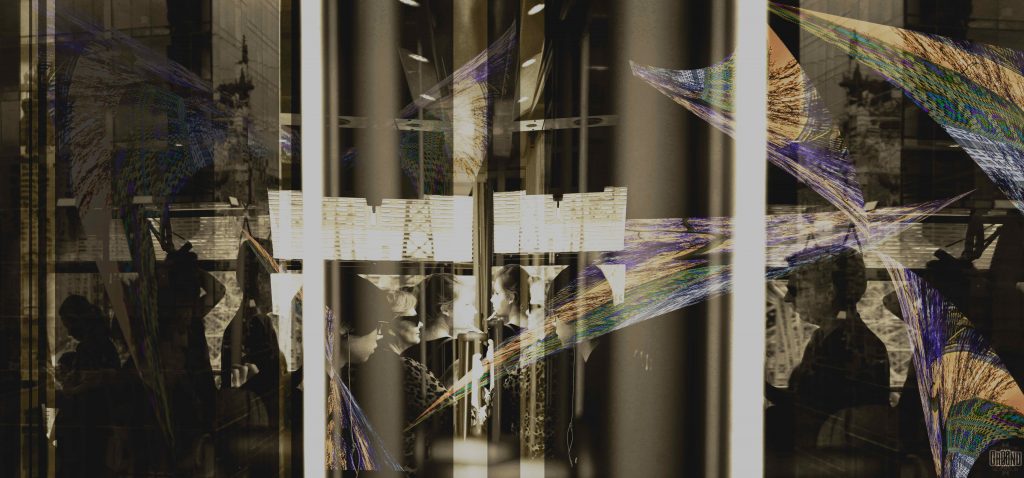

By digitally manipulating photographs and videos, Pax portrays his life in two different worlds. Colorful images represent Pax’s new life in America, where he has been based for the past two years. They appear alongside still photos that symbolize his life in Iran’s conservative Muslim society that suppressed both his artistic ambitions and lifestyle.

“I always was searching for a medium that would allow me to showcase my talents, and thought this was a good fit because I also feel distorted. My life was disturbing in Iran, and I thought I could capture what it’s like to relocate to a new country,” said Pax.

In Iran, Pax’s identity as a gay artist brought him multiple challenges. “I was constantly berated and physically abused and thought I should seek asylum,” said Pax. As a 16-year-old, he hung 20 of his best drawings around his bedroom before his brother ripped them down and beat him. Fearful that his work would be destroyed again, Pax began saving his work on a computer and studying digital photography and film production at a university in Iran.

Before he enrolled in film school, Pax spent two years studying in medical school at his parents’ instruction. But because his heart was not in it, he eventually quit to continue pursuing art.

During his second semester of film school, Pax met his then boyfriend who was living in Shiraz, Iran. To maintain their close relationship, Pax decided to enroll in some courses at Shiraz’s film school. That friendship, says Pax, made him comfortable about being openly gay in Iran.

“I was happy, very happy, because for the first time I was able to have a relationship with someone whom I imagined falling in love with. Someone I could like, and who helped me to realize that I am not alone and have friends who are the same as me,” said Pax.

Yet Pax’s life took a turn, in his early 20s when he and nine of his gay friends were arrested in Shiraz’s airport while bidding farewell to one of their friends. Homosexuality is illegal in Iran.

After his arrest, Pax said Iranian authorities raided his family’s home and despite finding no evidence of wrongdoing by himself and his friends, they were imprisoned for a number of weeks. Pax then was released, but not before he received 60 lashes.

“The day they announced my sentence I was so relieved that it was only lashes and volunteered to be the first to receive the punishment because I thought they were going to execute us. I never thought we would be freed and was prepared to die right there and then,” said Pax.

Two weeks after his release, Pax’s sister, who works as an attorney in Iran, gathered the necessary travel documents and papers to help him leave the country as a refugee. With his papers processed, Pax flew and relocated to Turkey in 2012 as an asylum seeker, a move he recalls as bittersweet.

“I always knew Iran wasn’t the place for me, but I never wanted to leave my family, not like that. I never intended for them to find out I was gay while in prison.”

But he added, “in Iran, countless people dream of living abroad and I was one them. I fantasized about what it would be like to live in a free country, among free people, people who have the right to vote, people who are free to think and eat the way they want. We saw that lifestyle on TV all the time.”

In Turkey, Pax’s art career began to flourish. In addition to drawing, he also became an activist advocating for the rights of the LBGTQ community, women and animals in Iran and elsewhere. “I promised myself that I would help others because there were still so many issues in Iran, not just in the LBGTQ community, but also for women,” said Pax.

Despite his struggles, Pax continues to use his skills to share stories about being openly gay in Iran…

Pax’s experience as a refugee inspired his first exhibition, titled “Division”. The collection consists of 17 images whose theme is the contrast between his real-life experience in Iran and his imagined life in America, to which he also applied for asylum and relocated from Turkey in 2014.

As a U.S.-based artist, Pax submitted his exhibition to several art festivals including Spectrum and Art Basel, both of which agreed to display the works. Art Basel, the annual contemporary art show in Miami, presented him with a rising artist award for being the most innovative contributor.

Pax recalled the accomplishment with pride. “That art venue changed my life and made me realize that all my hard work and efforts were not in vain. It proved I was right and that I was an artist, and that held a lot of value for me,” said Pax.

He also described his experience at Art Basel as emotional. “I cried a lot, and whenever I felt the tears coming, I would excuse myself. I was happy, you know, but my tears also were a result of everything I had endured. All the frustration, jail time, abuse, trauma and pressure I had experienced hardened me to the brink of depression despite always being a positive person. Yet art helped me to overcome that, and I felt I was chosen to endure that pain to help make a difference,” said Pax.

Pax’s background in film also led him to produce a documentary titled Why We Ran from Iran, which describes the real-life experiences of six LBGTQ Iranian refugees based in Turkey, expressed through quotes and poems written by Pax.

“I could have created a film portraying our torture and prison conditions in Iran and how we were living out of two suitcases while in prison – images that would have been upsetting for the audience. But instead, I produced a film that reflects LGBTQ voices from Iran in a way that Iranian viewers would not be ashamed to watch. I think an artist’s goal also is to create work that can alter perceptions of ideas or people that may be out of the ordinary,” said Pax.

Pax’s 2016 documentary has been submitted to numerous film festivals since its creation and appeared in seven, including that of the Farhang Foundation, an Iranian-American non-profit promoting Iranian art and culture. “I hope that my film will be unveiled in Iran one day and reach people there. Even if it changes one person’s view, it will be worth all my hard work,” said Pax.

Today, Pax works as a full-time video editor for the Voice of America’s Persian Service, but still makes time for his passion. “I’m an artist and have always known that. But my family put pressure on me to do something else. My family is indifferent to artists and doesn’t believe they have a real profession,” said Pax.

Like most Iranian parents, Pax’s expected him to be a doctor, lawyer or engineer. He said they were shocked when they discovered their son is a gay artist. “It was very heartbreaking for me and is one of the reasons my father hasn’t spoken to me since. My brothers were equally upset and the only family members I speak to today are my mom and two sisters,” said Pax.

Despite his struggles, Pax continues to use his skills to share stories about being openly gay in Iran and about his immigration to the U.S. “I feel that artists have a duty to help others. Whether it is through drawing, photography or dancing, art has allowed me to learn and share so much, and to never say no to anything.”