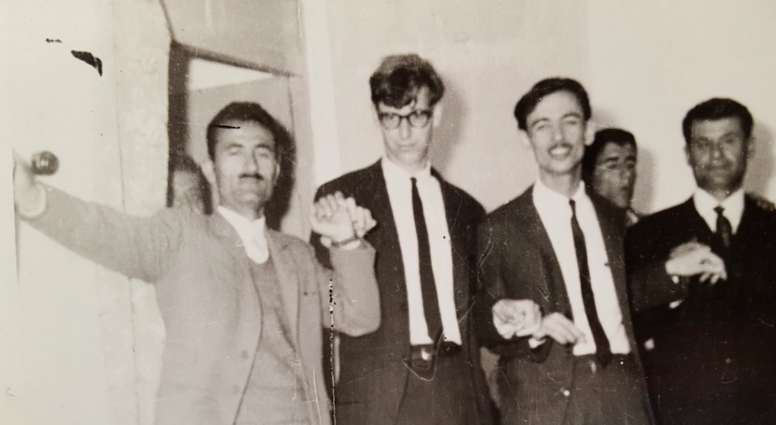

Ambassador John Limbert was one of the American hostages held for 444 days at the U.S. Embassy in Tehran following the Iranian Revolution. As a young man, he had been a Peace Corps volunteer in Sanandaj, Iran where he met his wife, Parvaneh Tabibzadeh and learned Persian. He not only fell in love with an Iranian woman but with Iran and its rich culture. He also spent time in Shiraz, living and teaching there between 1968-72.

Upon returning to the U.S., he finished his studies at Harvard University and did his doctoral thesis on Shiraz and Hafez, which later became a book. In 1973, he joined the State Department and held many high-level foreign posts. In August 1979, he went to Iran as a U.S. diplomat and worked at the Embassy until he and 51 others were captured and held hostage by the students, followers of Imam Khomeini line.

In fact, even though the storming of the U.S. Embassy may have been a spontaneous affair, under the pretext of the Shah’s admission to the U.S. for treatment, later the hostage crisis helped foment a silent coup against the provisional government of Mehdi Bazargan, helping to consolidate power by those who took over.

It also gave Reagan the presidency over Jimmy Carter.

Ambassador Limbert taught at the U.S. Naval Academy until his retirement in 2018.

He reads and speaks fluent Persian.

He is the author of three non-fiction books, Iran: Shiraz in the Age of Hafez: The Glory of a Medieval Persian City, Iran: At War with History; and Negotiating with Iran: Wresting the Ghosts of History.

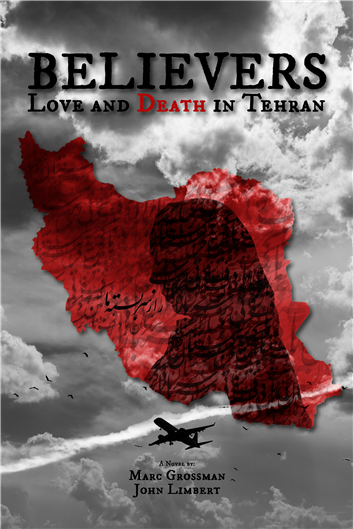

Recently, he and another former diplomat, Marc Grossman have co-written a novel that is set in Iran and in America.

A fictional story based on real characters and real events. Published in 2020 by Mazda Publishers, Life and Death in Tehran is a real thriller.

On the occasion of the Embassy take-over on November 4th which marks its forty-first anniversary, I had a talk with John about his novel and his thoughts some four decades later.

Of the Revolution, he says: “I admit that I called it wrong really from the beginning and in the direction that it went. The direction that it went – this rather harsh and brutal and intolerant direction that it went – certainly surprised me. I didn’t expect it. Nor did I expect that we and the Iranians would remain estranged for as long as we have.”

I did not expect the estrangement and the hostility to last so long. I was wrong.

You have recently written a novel. Tell us about the novel and its content. Why did you decide to write this novel?

The novel is “Believers: Love and Death in Tehran“. I wrote it with Ambassador Marc Grossman, the former undersecretary of state for political affairs and ambassador to Turkey.

The story is this. Nilufar Hartman, a young Iranian-American Foreign Service Officer, is assigned to the US Embassy in Tehran in the fall of 1979. She arrives in Tehran in the early morning of November 4, and spends the night at the home of her mother’s Iranian family. Before she can report to work the next day, she learns that the American Embassy has been occupied and the staff taken captive. When it soon becomes clear that there will be no early end to the crisis, Undersecretary of State Alan Porter, who had originally sent her to Tehran, asks her to remain there and keep him informed of developments.

With the help of her Iranian relatives, she assumes the identity of “Massoumeh”, a devout revolutionary. She ends up staying in Iran for almost nine years, through much of the chaotic 1980s, working in Mehrabad Airport, the morals police, and the offices of the powerful figures Mohammad Beheshti and Akbar Hashemi-Rafsanjani. She also falls in love with a young Iranian-American, also working for the U.S. government.

In July 1988, tragedy strikes and she flees Iran, barely escaping with her life. Feeling betrayed, she vows to have nothing more to do with the U.S. government and withdraws into academic life in a remote corner of New England. There she raises her son as a single parent.

Thirty years later, Porter asks her to return to Iran to stop a conspiracy to provoke a war with the U.S. She is reluctant to do so, but love for both countries compels her to return. Once in Iran, she must deliver Porter’s message to patriotic but suspicious Iranians, convince them to act, and evade Iran’s vicious secret police while escaping the country.

Who is the main character in your novel?

The main character is Nilufar Hartman, who becomes the devout “Massoumeh Rastbin” to work as a spy in Iran. Starting with our “what if?”, we had to create someone who could operate in Tehran without being detected. Someone resourceful who could “hide in plain sight”. Thus our character is a bi-lingual, bi-cultural young woman who also — thanks to her mother’s family — was at home in the Islamic world of the new order. Once we decided our hero was a woman, the choice seemed obvious. After all, where are the backbone, brains, and heart of Iranian society? Among the women, of course. It’s worth noting the women spies in Iran are currently in fashion. See the French TV series “The Bureau” and the Israeli series “Tehran”.

You were one of the former hostages. You spent 444 days in the U.S. Embassy in Tehran. Some forty years later, how do you feel today?

I did not expect the estrangement and the hostility to last so long. I was wrong.

Did you ever feel that your life was in danger?

Yes, particularly in the earliest hours and days.

There is a youtube film that Khamenei came to the Embassy to greet all of you guys. You said something quite funny to him when he asked you if you were comfortable? You said, well Iranian hospitality is great but at some point the guests would like to leave! How did you feel about this encounter?

I wanted to make a simple point: “I know how to treat a guest in my own space. You and your friends here apparently do not. You have thus violated the deepest traditions of your national and religious culture.”

Forty years of threats, accusations, and insults have accomplished nothing. It’s time to try something else.

After some four decades, how do you feel if you ever met your captors?

Why would I do that? I would like to hear them say, عجب شکری خوردیم ( we really messed up).

How did they treat you during the time you were their captives? Did they really think you were a spy?

Not well, despite their later claims that they did. Nine months in solitary was hardly good treatment. Many were sure of it. According to their own self-hate, why would anyone be interested in Iran’s history and culture?

As you know, many of them are now Eslah Talab ( reformists). What would you say to them if you ever saw them again?

As Obeid Zakani [ a satirical poet] says, مژدگانی که گربه طائب شد عابد و زاهد و مسلمانا ( let’s be happy that now the cat does not go after the mouse and has become pious).

As a seasoned diplomat during the most contentious relationship with Iran, what do you want to see happen?

I would like to see both sides use the proven tools of diplomacy: listening, careful language, and empathy. These tools haven’t been used in a long time and they have gotten rusty.

If you had a chance to meet Javad Zarif, what would you tell him?

I have nothing to tell him. He knows how to represent his country.

What is your message to Iranian and American officials?

Forty years of threats, accusations, and insults have accomplished nothing. It’s time to try something else.

Who is your favorite poet among all the Iranian poets?

I can’t rank them. Many have verses I love. Perhaps my special favorite is Hafez’s verse “Raaz-e-sar basteh-ye-maa bin, ke be dastaan goftand. Har zamaan baa daf o nei, bar sar-e-baazaar-e-digar. (See our deepest secrets, now sung by the storytellers. With flute and tambourine, from morning to night, at the gate of another bazaar).

It plays a vital role in the novel, and you will find it in beautiful calligraphy on the book’s cover.

A note by F.A.

The Iranian suspicion of foreign intervention in the affairs of Iran is not at all unfounded. It has roots in history. In 1953, the CIA and MI6 orchestrated a coup d’état against the elected and democratic government of Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh and helped bring the Shah back to power. The possibility of the Shah’s admission to the United States raised similar suspicions, inspiring the unfortunate hostage crisis which has led to 40 years of hostility between the U.S. and Iran.

In her book, Dr. Masumeh Ebtekar gives a different version of the Embassy take-over. Now, Minister of Women’s Affairs and previously holding the job as Minister of Environment, she was “Mary,” the spokesperson for the students who took over the Embassy.

In a critique of her book, John Limbert writes, “The irony now is that Ms. Ebtekar and many of her former colleagues claim to be fighting against the very system they helped create. Given their past, however, they hardly make convincing advocates for rule of law, political dialogue, and civil society. The very street gangs and revolutionary justice system whom Ms. Ebtekar and her friends once encouraged to seek out the hated liberals and compromisers have now turned against her. Who says there is no justice in the world?

In her book Ms. Ebtekar tells whoppers, apparently with a straight face. She also presents eloquent testimony of how one can convince oneself of the rightness of a course of action despite all evidence to the contrary. She repeatedly discusses, for example, how humanely and nicely we hostages were treated and how our easy conditions contrasted with our captors’ austerity and hardship. Does she believe that? She also insists that the occupation – which helped create the hysteria that the ruling men’s club in the Islamic Republic used to drive nationalists, liberals, moderates, traditional clerics into the political wilderness – strengthened Iranian democracy. Does she believe that as well?

At another point (p. 104), discussing the students handling of “revelations” of Embassy documents, she writes,

Political groups would contact us and ask us to publish documents against their rivals. We politely declined. We were determined to stay objective and to steer clear of political disputes.

Does she really believe that as well? I hope not, for if she does not believe all the above, then in her writing she is guilty only of hypocrisy, of being disingenuous. But if she does believe all of those things, that does not augur well for the future of Iran. That would mean she has learned nothing from the past twenty years, and is still denying simple reality – an excusable fault for a 19-year old student, but a serious problem for a 40-year old Ph.D., a parent, and a vice president of a country.”