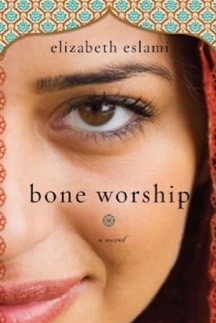

Excerpt from Elizabeth Eslami’s forthcoming novel, Bone Worship (Pegasus Books). Eslami will be reading with other California-based poets and writers at We are All Iran: A Literary Reading to Mark the Sixth Anniversary of the Iranian Elections, as part of the Global Day of Arts and Culture for Iran, Saturday, December 12, 2009, 2-4 pm, at the San Francisco Public Library, 2-4 pm (100 Larkin at Grove). More information at iranianamericanwriters.org.

****

It’s Sunday and time for the phone call to Iran. I sit in my room and listen through the thin wall. I can tell you exactly what he’ll say, but I don’t know what any of it means.

It’s a script. Though I can’t speak the language or translate the dialogue, I have heard him say the same things for so many years that I can repeat it—even mimic the sing-song voice and the pauses between questions and answers.

Both my father’s parents are there when he calls, and usually also some brothers and sisters. The calls are always on Sundays, in the early afternoon. He’s loud, beginning with a hello, then a question, cheerful, as if every word and phrase must be magnified to be understood so many thousands of miles away.

“Salaam!” My father grips the phone in the bedroom; he sits on the edge of the bed, hunched over like he’s speaking to his stomach. The room is filled with light when he calls. He does not think about his family on the other line—that it’s evening for them. “Ahuh, ahuh,” he keeps saying, impatient for his relatives to finish their sentences so that he can finish the call. There are minutes ticking by with each syllable, two seconds for a cluster of consonants. Money is being lost by the millisecond. “Baleh, baleh.” It cannot mean yes, but I looked it up, and it does. How angry are his yeses, traveling in pairs.

I wonder if every Iranian speaks this way. I can tell when my grandmother hands the phone to my grandfather, the minor alteration of tone, the faltering of letters. If the brothers and sisters are there, the phone is handed to each of them, one by one, to be asked the same series of questions by my father. How are – ? Children? Weather? Earthquakes? Health? He is on and off in an exact amount of time, maybe seven minutes. Seven minutes and then the cheerful goodbye. The phone slams down.

Throughout the call, I can hear my name and my brother’s. There are words connected to us, words for which there are no doubles, no method of explanation, or words he cannot translate. Internet. The names of American holidays. My father is frustrated when he has to say these words, trying to make them understand. They break the perfect timing of the script.

My father’s worst phone calls have been the ones from them. The night they called many years ago to tell him his promised bride, from his own hastegar, had killed herself. “Mota’assef am.” I am sorry but the woman you were to marry is dead by her own hand. The afternoon they called to say that his father’s heart was no longer good. Like fruit gone bad—their words sounded so casual over the phone. During these calls, they did not follow the script.

My father was the only one who could understand the language. The dead bride, the soft, rotten heart. If he had not told my mother, none of us would have ever known. He could have told no one, and over time, he could have forgotten his father’s heart. He could have forgotten a whole person. If he could forget the language, the words for things gone bad.

Uri used to ask to talk to them. “You can translate, Dad,” he would say. My father always made a face and refused.

They don’t sound like him, not at first, my relatives in Iran. I’m embarrassed to admit it, but at times I have picked up the other phone and listened to them, trying not to breathe over their cautious words. My father would be angry to know that I can hear his voice in a different way. Maybe he would try to yell at me, but his brain would not have switched over, and he would yell in Farsi. I don’t know why, but I think that would be worse than him yelling in English.

On rare occasions when my grandparents have called and my mother has answered, she has done her best. She speaks slowly, like she does to injured people. She tries to explain that my father is not home, and they try to repeat what she says, but she can tell that they don’t understand. It must be strange for her, for once, not to bring comfort via the telephone.

Then she gets nervous, because they start talking loud and fast at her, as if speed and economy will enable their words to find their way inside my mother’s brain quickly and make her understand. She feels like they’re yelling at her, but she can’t be sure. Eventually, she just hangs up. When my father comes home and my mother tells him he better call them back, that it sounded important, he looks nervous too. Maybe he’s afraid that she has learned his secret language. Maybe he’s afraid that they’re calling to tell him his father’s heart has stopped beating. And he will have to ask when, and they will tell him, and he will have to know it stopped back while he was eating potato salad in the hospital cafeteria.

The way my father talks to his parents – so confident and loud, without any introduction – makes me think they somehow know it’s him calling. That they expect it to be his voice. Of course, most of the time if they call and he does not answer, they hang up. There is a silent moment, paralysis. They hear me or my mother, voices that create confusion and fear in their heads. They wait a second, suspended, before hanging up.

“I bring this for you to look at,” my father says, throwing a photograph on the table in front of me just before dinner Sunday night.

I turn the photograph over in my hands. Everything is black and white. It’s a picture of a beautiful Iranian bride dressed in white with black, kohl-lined eyes. There’s a man standing next to her, a groom with hair as dark as ash.

“Who are they?” I ask.

“Is it my aunt.”

“She’s –” beautiful I start to say, and it’s true. She is.

If I could be this girl and push this boy’s bangs away from his eyes every night, if I could be made love to, if I could disappear in the white of that dress.

“No, wait. She’s my cousin, I think.” An aunt, a cousin, a daughter, is it, it is?

His language is going, disappearing. He is losing something he was born into, his

baby words, his schooling. In time he will lose his sisters’ names. I don’t know if this is because he has had to leave it behind, make space for all the loops and inversions of

English, or because he’s aging. With enough time, I am certain he will lose all language. He will sit in a chair, blow bubbles out of his lips like his fearful mother. He will be robbed of his own private idiom.

“Is not so strange, right? Not so scary to be bride?” he says, as if saying it makes it true.