When imagining a bookstore owner, you may envision certain stereotypical ideas—a quiet, reserved, studious individual who always has their head buried in a book. You probably imagine the average bookstore owner as someone who hasn’t had a particularly adventurous life. And if you were pressed to draw a biographical sketch, you might insist that the average bookstore owner spends most of their life in their head and in their books. But the owner of Ketab Corp, an online bookstore, defies many of these stereotypes. Bijan Kahlili has had a far more adventurous life than most people could dream. Kahlili was imprisoned for 11 days during the Iranian Revolution and less than a year later fled the country, immigrating to the United States. The books he took with him would send him on a brand new path.

“I was in hurry to leave Iran,” Kahlili said. “And in a way I fled. Therefore I did not have that much time to choose the books. As far as I remember I took with me Les Miserables by Victor Hugo, 2nd edition published 1956 by Amirkabir publishing company translated into Persian by Hossenali Mostaan and Humiliated and Insulted by Fyodor Dostoyevsky published by Safialishah publishing company, first edition in Iran, and translated by Rabbi Moshfegh Hamadani.”

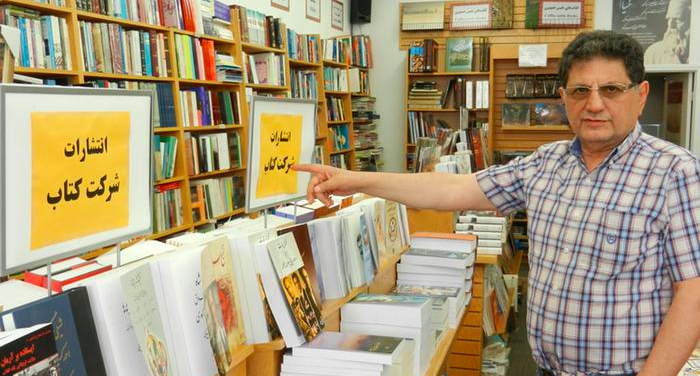

Books were life. Or, more specifically, books served as a very important part of life for Khalili, so important that he would bring 8 other books with him on his journey out of Iran and within 40 days of arriving in the United States, he opened a Persian bookstore in West Los Angeles. For 36 years, Ketab Corp. bookstore stood as a beacon of affirming texts for the Los Angeles Persian community before it closed in the summer of 2017. The store, like its online version, provided scores of titles on Iranian history, arts and culture, literature, and politics in both Persian and English. Both the generation who survived the tumultuous Iranian Revolution and immigrated to the United States and the generation who had never set foot in Iran could seek out a piece of Iran in a positive and community oriented place. But Khalili fears that the gap is widening between those who know Iran firsthand and the generation who don’t. Many young Iranian-Americans cannot speak or read Farsi so they’re unable to access texts that are written only in Farsi. This has Khalili worried about the future of the Iranian-American community.

“The immediate affect is the parents and the youth do not have much common to talk about and therefore they do not exchange their cultural matters together,” Khalili said. “In the long run, the new generation as a whole will not be able to access the cultural matters easily even if they want.”

And it may be inevitable that the next generation will begin to yearn for their cultural roots especially as the United States becomes increasingly xenophobic. Fortunately, Khalili plans to keep Ketab’s beacon shining bright for anyone who wants to immerse themselves in the historical, cultural, and contemporary works of Persians in Iran and abroad.

Visit Ketab Corp. online: http://www.ketab.com/