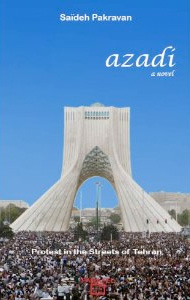

Azadi: protest in the streets of Tehran is a new novel by author Saïdeh Pakravan, set in Tehran after the rigged presidential elections of June 2009. It follows the lives of Raha, Kian and Hossein, three college-age individuals whose lives become intertwined against all odds.

EXCERPT

Nasrin

I know Pari has great connections but I still can’t believe it when we hear from her the very next day after our visit, with the time and place of our appointment with Karroubi. Pari tells us she will pick us up herself, not one to pass up a chance of establishing a connection with Karroubi as one never knows which way the tide may turn. Also, our dear relative always has to be center stage and as highly visible as possible. When she shows up, I see that out of deference to the high-ranking mullah we’re going to visit, she’s dressed in demure black—though in the expensive designer clothes she fills her suitcases with during the trips she takes every year to Europe. I’ve never known anyone so vain and can’t make up my mind whether she truly believes she’s this admirable person everyone loves or at least envies or if she is aware of how people truly see her. Still, she is doing us a great service today.

At Karroubi’s house, we are made to wait a short while in a living room with a beautiful Isfahan rug. A few other moraje’e—visitors—sit on folding chairs along the walls, one with a battered briefcase filled to bursting with papers. An aide soon calls our name and ushers us into a smaller room, lined with books, with a few armchairs round a coffee table and a desk in a corner. Hormoz has warned us three women not to look at Karroubi directly nor extend our hands to shake his but the Hojatoleslam stands up, shakes hands with all of us, then indicates the armchairs for us to sit down. Tea is brought. There are some shirini on the table as well as a platter of fruit. I don’t know why I expected him to make small talk and to at least mention the reform movement or the protests that followed the results of elections in which he was, after all, a candidate, but he doesn’t mention any of these topics. Instead, after a few polite sentences, he sits back and says that he’s listening. Hormoz starts to speak but Karroubi raises a hand to stop him. “I understand your concern as a father but from what I was told, this dokhtar khanom, this young lady, Raha Jan, dorosteh, correct? is the victim. I would rather have her tell me what happened.”

The Hojatoleslam is no ordinary mullah. Direct, serious but not stern, he looks at my daughter with the kindest eyes. I’m hoping she won’t burst into tears as these days, overwrought as she is, displays of affection or gentleness make her very emotional whereas the slightest confrontation or discussion turns her into a harsh, tough Raha whom I’ve never seen before. Now, sitting up very straight, she starts talking calmly and concisely. I’m both proud and awed by my daughter. Anyone not knowing her would find her insensitive. Only I can tell how strongly she holds herself in check. As Raha starts describing the demonstration she was in and how she was arrested, Karroubi looks around to make sure the bearded young man who is sitting at the desk takes notes on his computer, then says to Raha, “Where were you taken?”

“To the Ministry of Interior, to the bazdashtgah called manfi char.”

“Describe what happened. There’s no rush, take your time.”

She says that on the tenth day of her incarceration, two women guard came for her and took her to a room that looked like an interrogation room in a different part of the jail where there was no one else. They left, closing the door behind them, then three men came in.

“Were they in uniform?”

“No. They wore civilian clothes.”

“Would you recognize them?”

Raha says yes, absolutely. Then she goes on with her story. She says that the men attacked her, beating her and raping her and, her voice low, adds that they hurt her from behind as well. She takes deep breaths and has to stop from time to time. I can’t bear to look at her and instead stare at Karroubi’s feet in their thick white socks, no shoes or slippers, and think of how people make fun of the mullahs for always needing to be perfectly comfortable.

“Did they say anything to you?”

“Yes. They insulted me with obscene words and said this society didn’t need corrupt people such as myself. They said that my family and myself would have to leave the country because we’d never be able to hold our heads high again.”

Raha’s voice breaks but she manages not to cry. Now her head is down and again Karroubi tells her to take as much time as she needs. After a while, she adds, “One of the men kept yelling that he was giving me back my vote.”

“You don’t need to say any more. This is a terrible story, my dear child. You are a good, virtuous girl, I can see that your parents have raised you well. I will do everything to bring these thugs to justice but you know that this is not in our hands. Agha Karamati here will give you the name of a human rights lawyer and he will call her. You will tell her everything you told me and she will set this procedure in motion. One point is important. Do you have any documentation, did you by any chance go to the pezeshki ghanooni, the medical examiner’s office?”

I say that we took her to Shariati where they kept her several nights.

“So you have documentation. Did they take pictures?”

Hormoz says yes.

“That’s good. Your lawyer will need to present a strong case to this committee that has just been set up to attend to these matters. I don’t know how it functions as it hasn’t even started yet but I’ve had personal assurance from Aghaye Rafsanjani that they will look into all cases. Insh’allah, God willing, they will. At this point, I don’t even know if they will accept your case for review. Your lawyer will keep me informed of how this goes. May God give you all patience. A great injustice has been done. There has been too much of this, it is an insult to our country and to Islam. The idea that our young people could be exposed to these horrible goings-on is unbearable, there has to be a reckoning. I will do all I can to help bring the perpetrators to justice.”

He shakes hands with all of us. He takes Raha’s hand in both his. She thanks him and says, “I want you to know that I voted for you.” He smiles slightly and I can tell he’s pleased. He pats her hand and lets it go. Agha Karamati comes out with us, gives Hormoz the address and the telephone number of the lawyer and tells us he will phone her right away and we leave. Outside, Pari starts to talk to Raha but I can see from my daughter’s breathing that she’s not well. As we reach the car, she says, “Can I be alone in the car for a few minutes?”

Pari, Hormoz and I walk to the end of the parking but I can hear my child’s terrible sobs despite the car’s closed windows. Then she starts shrieking. Pari raises her eyebrows and says, “Eva! Wow!” It’s all I can do not to slap her. Hormoz holds my arm until the crying stops, then we walk back to the car. While we’re driving home, Homa calls me on my mobile but I tell her I’ll call her back. I’ve just told Pari I don’t want to talk about anything, I’m too tired, and I don’t want her to listen in. When she drops us off and we go upstairs, I call Homa to tell her how things went. She asks me if Pari behaved and I have to say that for once she didn’t say anything at all. I add that we’re all grateful for her help. Homa knows her sister. All she says is “khoda ra shokr, thank God.” Then we talk about the next steps.

Please visit saidehpakravan.com for more information about “Azadi” and for purchasing information.