The visit by Pakistan Prime Minister Imran Khan to Iran on April 21-22 will be a major event in regional politics. Whether it will be remembered as a landmark event, time only will tell. At its most obvious level, the visit signifies that Pakistan prioritises good relations with Iran. Indeed, in the backdrop of acute tensions in India-Pakistan tensions, with the two countries almost reaching the brink of war recently, the management of a cooperative relationship with Iran is very much in Pakistan’s interests.

Historically, the Iran-Pakistan relationship is one of great complexity where contradictions keep on surfacing every now and then. From Iran’s viewpoint, Pakistan’s close ties with Saudi Arabia and its cold-war era role as the US’ key ally had introduced into the relationship a major contradiction through the entire period since the Islamic Revolution in 1979.

Through the eighties and nineties, Pakistan became a battlefield where Saudi-Iranian rivalries played out as sectarian violence causing much bloodshed and suffering. Iran kept out of the US-Saudi-Pakistani sponsorship of the ‘Afghan jihad’ in the 1980s and preferred to have its own Mujahideen groups resisting the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan. The trust deficit was palpable.

Without doubt, one of the prime motivations behind the creation of the Afghan Taliban in the early 1990s by Pakistan and Saudi Arabia (with tacit US encouragement) was that such a movement rooted in Wahhabi ideology would be virulently anti-Shia, anti-Iran. This was not a far-fetched agenda, as the execution of 9 Iranian diplomats by the Taliban in the Iranian consulate in Mazar-i-Sharif in 1998 showed.

However, the Iran-Pakistan ties as such never really took the form of open hostility. They were more in the nature of ‘great game’ rivalry than of two indomitable adversaries locked in a struggle to weaken or destroy each other. Outsiders, especially Indians, often fail to understand the pattern of ebb and flow of tensions in Pakistan-Pakistan relations. Also, what is often overlooked is that Iran has continued to regard Pakistan as a brotherly Muslim country, which resorted to erratic behaviour more out of instigation by the Gulf states and the US than out of malice toward Iran.

Suffice to say, the underlying premise in Iran’s strategy has been that the relations with Pakistan can change only in an environment where Pakistan begins to assert its strategic autonomy and pursues independent foreign policies. Sure enough, Iran sensed that Imran Khan’s ascendance as prime minister last August presented itself as a rare opportunity in that direction.

As Tehran would see it, here was a democratically elected, charismatic Pakistani leader who not only cherished his country’s Islamic identity but was proud of it — and yet was not beholden to the Saudis or the UAE — and espoused Muslim unity, and, more importantly, seemed to be in empathy with Iran’s politics of ‘resistance’ and often voiced opinions against the US hegemony and, in particular, against continued American military presence in the region.

Succinctly put, Tehran estimated that it could do business with Imran Khan. This belief also drew strength from certain other factors. If Pakistan’s refusal to join the Saudi-led war in Yemen contained a big message for Iran as far back as April 2015, the unprecedented visit by the Pakistani army chief Gen. Qamar Bajwa to Tehran in November 2017 underscored that the Pakistani military, in a break with the past, sought to open a new page in relations with Iran. In retrospect, these were two defining moments in the Iran-Pakistan relationship.

Overall, Tehran could see that Pakistan was keenly exploring its strategic options in a complicated regional environment due to the endless war in Afghanistan, the deepening chill in Pakistan’s relations with the US (since 2011), the intensifying US-China rivalries and the incipient new Cold War conditions that began spilling over to the region.

No sooner than Imran Khan took office as prime minister in August last year, Iran’s foreign minister Javad Zarif travelled to Islamabad to open a dialogue with the new leadership and to invite the Pakistani leader to visit Tehran. President Hassan Rouhani telephoned Imran Khan and personally conveyed the invitation. But if Iran had hoped that Imran Khan would choose Tehran for his first visit abroad, that was not to be.

On the contrary, Tehran felt disappointed that Imran Khan prioritised the crown princes of Saudi Arabia and UAE, Iran’s main regional adversaries, as his principal interlocutors. But then, Iran was savvy enough to understand that Imran Khan had has own reasons to make such a shrewd choice to lavish attention on the two crown princes, given the criticality of Saudi and Emirati financial assistance to bail out the Pakistani economy.

However, what came as a rude shock was the terrorist attack in Sistan-Baluchestan province of Iran by a Pakistani suicide bomber in February in which 27 Iranian guards were killed and thirteen people were injured. Iran suspected a Saudi-backed terrorist group Jaish ul-Adl Takfiri, which is affiliated with the al-Qaeda. It was the deadliest terrorist attack in Iran for years and Tehran was furious, alleging that it was “planned and carried out from inside Pakistan.” The Iranian military commanders even pointed the finger at Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence for involvement in the terrorist attack. They vowed revenge. In an extraordinary move, the commander of the Quds Force Gen. Qassem Soleimani threatened Pakistan.

However, tempers cooled down eventually and Tehran has since moderated its stance that Pakistan was not acting sufficiently enough to prevent the activities of terrorist groups. The February incident becomes a case study of Iran’s handling of cross-border terrorism originating from Pakistan. No doubt, Iran has good intelligence presence within Pakistan and has a fairly accurate idea about the activities of the terrorist groups operating in Baluchistan province. But Iran never contemplated any military operations by way of retaliation such as conducting ‘surgical strikes’ inside Pakistan or instigating extremist groups based in Afghanistan to hit at Pakistan. Instead, Tehran preferred to suspend its disbelief and consistently tried to seek the cooperation of Pakistani security agencies and the military leadership to curb terrorism. The logic behind this approach is understandable.

One, Iran could see that Pakistan itself was a victim of terrorism. Two, Iran did not view Pakistan in adversarial terms and there were no serious unresolved disputes as such between the two countries. Three, Iran gave the benefit of the doubt to the Pakistani security establishment since there is a serious security climate indeed prevailing in Baluchistan and Islamabad had its hands full in coping with it.

Four, most important, Iran’s strategic priority is that it has a cooperative, friendly neighbour on its eastern borders at a juncture when it is coping with a tough neighbourhood to the south and southwest. In all this, what needs to be factored in is that Tehran’s top priority is always that Pakistan does not get sucked into the US-Saudi-Israeli strategy directed against Iran. Thus, in many ways, Tehran’s approach of strategic patience made great sense.

CPEC lurches toward Iran

Imran Khan’s visit to Iran on Sunday can be seen as vindicating Tehran’s nuanced approach to the relations with Pakistan. Surely, border security will top the agenda of the discussions in Tehran between the two leaderships. Supreme Leader Ali Khamenei will be receiving Imran Khan.

Tehran is indeed seeking a much broader engagement with Pakistan than has been possible so far. The Iranian approach presents a study in contrast with the Modi government’s policy of ‘no-dialogue-unless-terrorism-ends’. Fundamentally, Iran sees that Pakistan is on the cusp of change and its past policies of using terrorist groups as ‘strategic assets’ are becoming increasingly unsustainable.

According to media reports, Pakistan has promised to boost security cooperation with Iran, saying that the two neighbouring countries are considering fencing the 950-kilometre long common border to keep terrorists in check. The Pakistani army spokesperson and director-general of Inter-Services Public Relations Major General Asif Gafoor has been quoted as saying, “We both are considering fencing the border so that no third party could sabotage the brotherly and friendly relations through any nefarious act.”

Looking ahead, expansion of trade relations and the completion of the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project are sure to figure in the agenda of Imran Khan’s talks in Tehran. Iran has completed its part of the gas pipeline project and is awaiting Pakistan’s fulfilment of commitments. In the past, Pakistan tried to mediate between Iran and Saudi Arabia but all those diplomatic efforts failed to achieve the desired results.

Reports suggest that Imran Khan would reiterate Pakistan’s call for unity among all the Muslim countries to deal with common challenges. In reality, though, Pakistan lacks the clout to mediate the rivalry between Saudi Arabia and Iran, two regional powerhouses in the Muslim Middle East.

Nonetheless, Pakistan’s positive neutrality in the Iran-Saudis tensions itself works in favour of Tehran. Imran Khan has reiterated more than once that Pakistan will no longer act as a hired gun in someone else’s war, showing his resolve to pursue an independent foreign policy. As for Iran, it is critically important that like Turkey and Iraq on its western border, Pakistan on its eastern border also repudiates the US’ sanctions and has an open mind on expanding trade and economic cooperation with Iran.

Immediately after the visit to Iran, Imran Khan will proceed on a visit to China on April 25-28 to attend the Belt and Road forum’s second summit in Beijing. Whether it is by design or a mere coincidence is unclear. But the fact of the matter is that Iran has expressed interest in joining the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) project. To be sure, Iran with its vast energy resources can play a major role in making the CPEC a grand success.

On the other hand, China also has deep interest in expanding and deepening Iran’s participation in its Belt and Road Initiative and to use Iran as a regional hub. China is figuring as the number one strategic partner in Iran’s calculus and Beijing too attaches high importance to the relations with Tehran. Something of this is bound to rub on the Pakistani thinking. Again, Russia has signalled interest in promoting the Iran-Pakistan gas pipeline project.

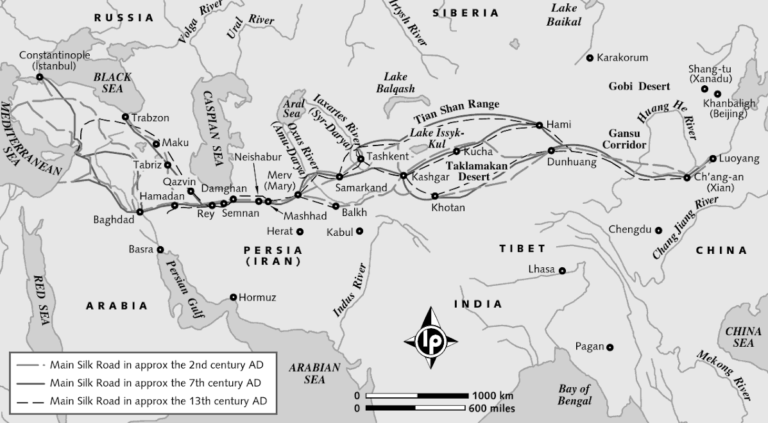

All things taken into consideration, therefore, it is conceivable that Imran Khan’s visit may turn out to be a defining moment leading to Iran’s link-up with the CPEC. The outcome of the visit will be keenly watched for signs in this direction. Interestingly, according to reports, Imran Khan will have a stopover in Mashhad in northeastern Iran, which used to be a major ‘junction’ on the Silk Road.

Clearly, if such a thing happens, the geopolitics of the region will transform phenomenally. Basically, Iran and Pakistan are on the same page in seeking greater Eurasian integration. Incidentally, Iran’s membership of the Shanghai Cooperation is under active consideration at the moment, too.

However, Pakistan would run into headwinds in optimally developing its relations with Iran. To be sure, Saudi Arabia and the UAE will be monitoring closely and are sure to curb Pakistan’s enthusiasm to give verve to the ties with its western neighbour. It is with an eye on Iran that Saudi Arabia is making investments in Gwadar and the Baluchistan province.

There are other factors too that inherently limit the scope for a dramatic surge in Iran-Pakistan relations. Clearly, it is highly unlikely that at a juncture when Pakistan is nearing a $12 billion IMF loan deal, Imran Khan will risk annoying Washington by taking a big leap forward in relations with Iran. Again, any Pakistani expectations of Tehran abandoning its expanding strategic ties with India for the sake of stabilising its relations with Pakistan will be quite unrealistic. Above all, it is apparent that the Pakistani and Iranian approaches to the Afghan problem are quite divergent. In fact, Tehran, Kabul and New Delhi are working together in a trilateral format based on common interests.

The bottom line is that Imran Khan’s Iran visit throws into relief the shifting sands of regional politics. Consider the following. To be sure, Saudi Arabia and the UAE are bailing out Pakistan’s economy and Pakistan reciprocates by acting as a provider of security to these Arab regimes. It is a profound relationship, which is time-tested and mutually beneficial. But, having said that, Riyadh and Abu Dhabi are also lately strengthening their partnership with India (which they see as an emerging Asian power) and are even promoting India’s association with the Organisation of Islamic Conference, which has historically provided a platform for Pakistan to berate India and condemn Indian policies.

Suffice to say that Imran Khan’s visit underscores that Pakistan is ‘de-hyphenating’ its strategic alliance with the Saudis and Emiratis from its policies aimed at improving its relations with Iran. No matter the US-led containment strategy against Iran with which these two Gulf states are closely associated, Imran Khan’s visit signals that Pakistan intends to explore the potentials for a constructive engagement of Iran.

Viewed from Iran too, it is clear that any improvement of relations with Pakistan cannot be at the cost of its expanding cooperation with India, which has a promising future. At the same time, Iran cannot but be conscious that India is developing a robust relationship with both Saudi Arabia and the UAE (as well as with Israel) and, furthermore, Delhi will not defy the US sanctions against Iran and is actually cutting back on its imports of Iranian oil and is substituting with increased imports of Saudi oil.

What emerges is a complex web of regional alignments that are very dynamic both because of the numerous variables in regional politics as well as due to the impact of big-power competition, which is itself yet to crystallise and whose future trajectory is difficult to predict. All regional states are hedging — India, Pakistan, Iran, Saudi Arabia and the UAE.

On the whole, Pakistan has been quick on its feet to adapt to (and exploit) the emergent trends on the geopolitical chessboard. At the moment, it has a stronger hand than Iran in regional politics. It is possible to conclude that Imran Khan delayed his visit to Iran with deliberation and has timed it at a juncture when Iran’s need for good relations with Pakistan is greater than Pakistan’s.