PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

The Ratification Mystery

Tuesday, 6 May 2003 (continued)

Let me give you a much happier story, about the work of our Indian colleague, a businesswoman from Delhi, who’s been contacting, advising and organising Afghan women producers of handicrafts to help them improve their output and make it marketable in the West. The first exhibition of such goods was held on Women’s Day, 8 March, but the goods were either not of a very high quality, or were presented at unreasonably high prices. I personally could not bring myself to buy anything form that exhibition because I thought that would be charity rather than help.

Nearly three months later, some of the same women have come back with products of much higher quality, and reasonable prices. Today, a lady brought in a leather shoulder bag and a leather folder that had been modeled after a sample shown to her two days ago. She had not taken the sample with her, nor had she had any drawings to help her with the design. All she had had to work with had been the image she had memorized. To that, she had added some new features, producing two very beautiful items. What’s more, with advice from our colleague, she had reduced the raw odour that you can smell from some leather products here for days or even weeks. Given time, the women producers could turn into serious rivals for men.

Two political notes: Mr Karzai who made lots of people angry last week by saying most of the Taliban had been good Moslems and patriots, has now given another speech in which, according to news reports, he said the Taliban had not only destroyed Afghanistan’s material wealth, such as agriculture in the Shamali plains, but also the country’s culture. Such seemingly contradictory statements could damage any leader’s credibility, provided the news is correct and it reaches the public. But as far as I can see, most people don’t read the newspapers and many of them don’t have power and cannot afford batteries to listen to the radio, and if they did, they might prefer to listen to music. So maybe it does not matter, after all.

Secondly, the continuing mystery over Afghanistan’s ratification of CEDAW, the UN’s Convention for Elimination of All forms of Discrimination Against Women. This is a comprehensive document which, if applied, would put women and men on equal footing in all areas of life. It has been signed by 170 countries, and ratified, that is turned into legislation, by most of them. Some countries have ratified CEDAW with ‘reservations’, i.e. they would not commit themselves to every single item in it because of ‘cultural’, political or other reasons.

There are a few countries that have not signed it, including Iran, and a few that have signed but not ratified it, including the United States, where there is a lot of pressure against ratification from women’s groups opposed to abortion, because the convention ‘affirms the reproductive rights of women’. The US signed the convention on 17 July 1980, the same day as the Soviet Union. Afghanistan signed it a month later, when it was governed by the People’s Democratic Party of Afghanistan, backed by the Soviet troops that had entered Afghanistan less than a year earlier.

Afghanistan’s ratification of CEDAW, however, came only about two months ago in a UN announcement that said ratification had taken place, without any reservations, but did not say how, or by whom. Now, ratification would either need a parliament, which does not exist in Afghanistan yet, or a government with legislative powers, but the Afghan government has said, as far as I know, that it has no idea how the convention was ratified. The only possibility is that someone with even more authority over Afghanistan than its current administration has decided that the convention should be part of Afghanistan’s laws, even if the people and their various leaders/rulers/representatives have no idea how this has happened or even, in some cases at least, what the convention is all about.

The practical significance of CEDAW will arise if and when a case is brought in front of a court in Afghanistan with a woman demanding the rights which the Convention promotes, but which could be diametrically opposed to some Afghan tradition, or an interpretation of some Islamic precept. What will the court rule and how will that ruling be implemented? It may well be some time before such a case arises, but it is not clear if by then there will indeed be a majority view in Afghanistan in favour of CEDAW. If there is no majority, then the convention will not be applicable in practice and the cause of women’s rights may in fact have been damaged rather than served.

[The United States is one of seven UN member states that have not ratified the convention. The others are Iran, Nauru, Palau, Somalia, Sudan, and Tonga, CEDAW 2011 – source. In November 2010, when the US Congress was debating the ratification of CEDAW, it heard testimonies in favor of ratification from women’s rights campaigners from Afghanistan who said CEDAW’s ratification in 2003 had led to significant improvements. See, Wozhma Frough, ‘CEDAW ratification [by the US] would be a triumph for Afghan women’; Dr. Sakena Yacoobi, Founder and Executive Director, Afghan Institute of Learning, ‘Statement for the Record’,18 November 2010.]

Wednesday, 7 May 2003

The best I can give you today is an account of my first meeting at the Ministry of Women’s Affair’s Gender Advisory Group, or GAG, which in spite of its rather unfortunate acronym, is quite vocal. Today there were thirty of us – five men – in a conference room for a planned two hour meeting which continued for nearly three, without finishing all the items on its agenda.

The participants, working in the Ministry of Women’s Affairs, various UN agencies, and the German and Norwegian embassies, were from Afghanistan, Iran, Germany, Britain, the Philippines, US and Norway. Between them, they have the responsibility of ensuring that gender is taken into account in whatever activity is undertaken in the government departments that they support.

The issues being discussed included elections and ways of encouraging women to vote and stand as candidates; women’s participation in the preparation of Afghanistan’s new constitution; education; and health. One of the most important topics in all the discussions about women’s social participation has been the lack of security, which threatens women in many parts of Afghanistan, including parts of Kabul. To deal with this, women’s groups have asked for women police officers.

Recruitment efforts over several months have resulted in only 40 women joining the police force. Of these, 12 are mid-ranking officers; 28 are policewomen, 13 of whom are illiterate and have had to be put through an intensive literacy programme. A recent ad to fill 400 vacancies at the constable level attracted 750 applications with the minimum of 6 years of schooling that is required, only 20 of them women. Of the 20, only 10 are physically fit to join the force. The reasons for the difficulty of recruiting Afghan women into the police force included the false perception that applicants had to be at least 175 centimetres tall, whereas the required minimum height is 165cms.

Other obstacles include the reluctance of families in the provinces to allow their daughters to enroll in the police college in Kabul because of accommodation problems that the girls are certain to face. It is only girls living in Kabul who could enroll in the college, while staying with their families. In the past – many, many years ago – girl students would feel secure staying at Kabul University’s dormitory, but nowadays families do not have such confidence.

Another, possibly bigger, problem is the public’s lack of confidence in the police force itself. After so many years when men with guns have ruled Afghanistan with impunity, people do not have much respect for the police. Instead of seeing the police force as protectors of their safety, many regard it as a power that makes them feel unsafe.

A view expressed strongly at the meeting was that the media could help counter this image by publicising what the police force does for the public. The trouble is that such publicity will not work if the police do not in fact do much that the public really appreciates. Still, someone asked me if I could help produce an educational radio drama to put across a positive image of the police force.

One idea, of course, would be to produce dramas about the police force which show women officers at work. But something similar to the Hollywood series, the Police Academy, the British TV series, the Bill, or American series such as LA PD and Miami Vice – for instance ‘Wazir Akbar Khan Blues’ – is not likely to give credibility to the police force in Afghanistan. What could be done, I suggested, would be a documentary series on the 40 women who have joined the police force that would explore the reasons why they had done so, and what they had gotten out of it. I personally hope something like this is made because it would be immensely educational.

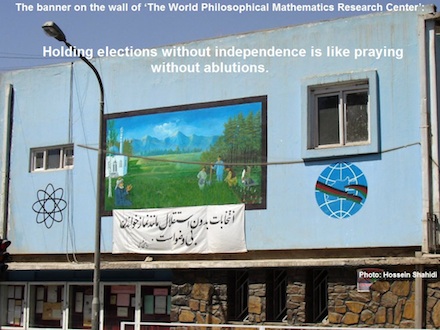

The newspapers today reported yesterday’s demonstration in Kabul over the cost of living, by about one hundred people. The protest had been organised by a former university professor, Mohammad Seddiq Afghan, who is introduced as the Director of the World Centre for Mathematical and Philosophical Research, based in Kabul. There are also pictures of the professor, wearing a beard as well as a suit and tie, addressing the crowd.

I learned from my colleagues that the doctor has engaged in other headline grabbing activities in the past. One of these is said to have been a prediction in 1991, when the PDPA’s Dr Najibullah was the President of Afghanistan, that violence in the country had come to an end and henceforth ‘blood will not flow form anyone’s nose’. About a year later, the Mojahedin overthrew Dr Najib and took Kabul and then started the faction fights that destroyed much of the city. With such a track record, one wonders about the chances of success for the protest the scientist and philosopher has now started.

Thursday, 8 May 2003

Another strange evening of entertainment. For the first time in a very long while, here or anywhere, tonight I watched a movie on television, Bridget Jones’s Diary, something I would not have done in London. On the news channels, the Israelis were carrying on with their ‘goal-driven performance’, to use the language of the ‘road-map’. And Afghanistan TV was showing an Indian film, dubbed into Persian with the original Hindi also fully audible. All in all, life as usual, anywhere.

The last thing I did at the office was facilitating our third meeting of four leading Afghan women journalists who will form the core group for organising quarterly conferences of women journalists from across the country to share skills and experience and gain a stronger voice. As I’ve noted before, this is the first time such an event is being prepared in Afghanistan, a very inspiring and encouraging experience, which if successful will change the minds of many men, and some women, about women’s abilities.

An earlier meeting was at the Aina Center, for commissioning a film of the 8 March celebrations, shot by the Afghan camerawomen who’ve been trained there. I then went to see the editor of the satirical magazine, Zanbel-e-Gham (the Basket of Sorrows), a very sweet and humble man who, as I’ve said earlier, insists on publishing his magazine in calligraphy, and not very highly polished calligraphy at that, rather than have it typed. Repeating what others have already told the editor, I said the copy would work a lot better if it were typed.

On a sad note, my British colleague, Linda, learned today that her father had passed away in South Africa, where he had been living for some time. This came only a day after she had managed to book herself a flight to Britain in a week’s time to meet him. We all gathered in a circle in one of our rooms and our Filipina colleague, Ermie, said a prayer for Linda’s father. Two days ago, we had had another service for an Afghan friend who’d lost his grand-father. At that service, our younger office assistant, Turiyalay, recited verses from the Quran very beautifully.

An Afghan colleague told me that today she had heard a Christian prayer for the first time and had realised that it was almost identical to what would be said at a Moslem memorial service. It seems we all have the same faith, she said, but people with wealth and power get us to fight each other in the name of religion and then leave us in the ruins and misery created in the fighting. Such an experience and observation would not have been possible without an international, multi-faith community here. Perhaps another reason for being grateful for the UN’s presence in Afghanistan.

***