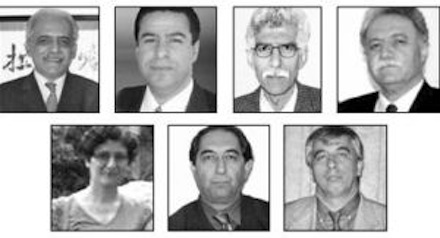

Photo: Educators affiliated with the Bahai Institute for Higher Education who have been imprisoned in Iran, from left to right, top: Mahmoud Badavam, Ramin Zibaie, Riaz Sobhani, Farhad Sedghi; bottom: Noushin Khadem, Kamran Mortezaie, Vahid Mahmoudi (Bahai World News Service)

The Salvadoran jurist Reynaldo Galindo Pohl died this year at age 93. A former education minister and president of El Salvador’s National Constitutional Assembly, Pohl spent much of his career pressing for human rights, first as a member of the Inter-American Commission on Human Rights and later as his country’s ambassador to the United Nations. News of his death barely registered outside Latin American diplomatic circles. But the more than seven million global adherents of the Bahai faith marked it with deep sadness. They remembered Pohl as the tireless diplomat who shed light on the persecution of their co-religionists in the Islamic Republic of Iran at a time when few others were paying attention.

From 1986 to 1994, Pohl served as the U.N. Human Rights Commission’s special representative on Iran. The Iranian regime, he found, was subjecting its largest non-Muslim religious minority to a systematic campaign of cultural eradication. In 1993, Pohl disclosed a chilling memorandum written by Seyyed Mohammad Golpaygani, then secretary of Iran’s Supreme Council of the Cultural Revolution. The Golpaygani memorandum, as it came to be known, set out a national policy for dealing with the “Bahai question.” The Iranian government, Golpaygani forthrightly recommended, must ensure that “progress and development are blocked” for Bahais.

The centerpiece of the policy was an express ban on Bahais’ obtaining postsecondary education. They “must be expelled from universities, either in the admissions process or during the course of their studies, once it becomes known that they are Bahais,” Golpaygani wrote. Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei approved the memorandum, “In the name of God!”

Two decades later, the rule barring 300,000 or so Bahais from Iran’s colleges and universities remains in place. It is enforced with particular vigor by the hard-line government of President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad. Even before Pohl’s exposé, the Bahai community had begun seeking ways to educate its youth. Those efforts culminated in the establishment of a secret distance-education college operated by hundreds of volunteers inside and outside Iran. Despite tremendous logistical constraints and personal risks, the college has been producing impressive results, with many of its students going on to graduate programs at prestigious Western universities. The college is a testament to the ingenuity and resilience of this embattled group.

Sadly, however, a severe regime crackdown begun last year threatens to finally realize Golpaygani’s dream of culturally erasing Iran’s Bahais.

The Bahai faith was founded in mid-19th century Iran by the mystic Baha Ullah, who proclaimed himself the messiah foretold by all world religions. Baha Ullah preached the unity of humankind and called for racial and gender equity—notions that directly contradicted the traditionalist precepts of majority Shiite Iran. Worse, Baha Ullah’s claims of divine revelation came after those of Muhammad, viewed as the “last prophet” by Muslims. As a result, Baha Ullah and his followers drew the enmity of Iran’s clerical class and were subjected to intense persecution. Nevertheless, the Bahai religion gradually made inroads inside Iran and across the Middle East and North Africa, winning converts even in Europe and the United States.

Under Mohammad Reza Shah Pahlavi, the Bahais of Iran generally thrived. While the shah brooked no political dissent, he was committed to improving the lot of the country’s women and ethno-sectarian minorities by abrogating ancient laws that relegated them to second-class status. Despite occasional outbreaks of anti-Bahai mob violence instigated by the clerics—tolerated by the shah when his political power was at an ebb—a number of Bahais reached positions of prominence. In 1971, for example, a Bahai architect designed the Azadi tower, in Tehran, that has since become the city’s symbol.

With the collapse of the shah’s regime and the rise of radical Islamists in the aftermath of the 1979 revolution, clerical hatred for the Bahais once again gripped Iran. “Will there be either religious or political freedom for the Bahais under an Islamic government?” an American scholar, James Cockroft, asked Ruhollah Khomeini soon before the ayatollah returned to lead Iran after 14 years in exile. “They are a political faction; they are harmful; they will not be accepted,” Khomeini sternly responded. In drafting the new Islamic Republic’s Constitution, Khomeini and his allies extended a quasi-protected status to three “official” minority religions—Judaism, Christianity, and Zoroastrianism—but excluded the “heretical” Bahai faith, with some of its holiest sites located in the modern-day state of Israel—Iran’s new archenemy.

During the early days of the clerical regime, Khomeini’s anti-Bahai crusade was quite overt, with hundreds of adherents jailed and summarily executed along with thousands of leftists and elements of the former regime. But as the deteriorating human-rights situation in Iran became a focus of international attention, the regime’s anti-Bahaism took on a subtler character. Thousands were terminated from public jobs, and private employers who dared hire Bahais risked criminal prosecution. Golpaygani’s infamous memorandum, codifying the exclusion of Bahais from the country’s higher-education institutions, was part of that second wave of relatively invisible repression.

“Regard man as a mine rich in gems of inestimable value,” Baha Ullah instructed his followers. “Education can, alone, cause it to reveal its treasures, and enable mankind to benefit therefrom.” That education and self-improvement are basic tenets of the Bahai faith renders the clerical regime’s policy of barring its adherents from higher education especially cruel. But it also means the community has been remarkably tenacious in seeking credible alternatives to Iran’s colleges and universities.

In 1987 the Bahai Institute for Higher Education was set up as an underground, distance-learning program for Bahai youth. At first the college was quite informal. “The students would meet in the basements of private homes,” Behrouz Sabet, a Capella University faculty member and board member of the Council for Global Education, who has been assisting the institute with research and curriculum design for more than 20 years, told me. Sabet, who immigrated to the United States in 1979, was teaching at the University of South Carolina when institute directors in Iran contacted him, asking for help with translating and developing curricular material. At the time, he recalls, the college was quite informal. “Someone who had chemistry expertise would lecture the students on that topic, while someone else with a biology background would share that expertise.”

Gradually, however, the institute took on a formal character, with more attention devoted to course design and sequencing. With the advent of the Internet and increasing assistance from allies abroad, the college’s curricular standards were bolstered and a wider range of majors and concentrations was introduced. Today the institute offers 32 university-level programs across five faculties. It accepts about 450 first-year students each year, out of, on average, about 1,000 applicants. “Once it went online,” Sabet explained, “the BIHE revised all of the courses and classroom procedures.” Moodle, an open-source, online learning platform similar to Blackboard, allowed faculty and course designers to preload all content. Students could submit assignments to be graded by tutors inside and outside the country. Faculty members could also choose to incorporate other interactive media into their courses.

Bahais are also persecuted across much of the Arab Mideast. Knowing that BIHE degrees could be of practical use only in the West, administrators emphasized English-language instruction very early on. In 2006, Jaleh Dashti-Gibson was working at the University of Notre Dame’s Kroc Institute for International Peace Studies when she volunteered to serve as an English-as-a-second-language tutor for the institute. “The ESL courses are self-paced,” she remembers. “So they need an army of tutors to help with grading and conversational instruction.” After undergoing Internet-based training, Dashti-Gibson was assigned to a group of 10 students who needed to master English very quickly while also completing their substantive coursework, much or sometimes all of which was in English.

The obstacles were enormous. “We were asking them to learn to think critically in writing, to develop arguments, and account for counterarguments,” Dashti-Gibson, today an administrator at the Green Acre Bahai School, in Eliot, Me., recalls. “At the time, I was working at Notre Dame with high achievers who had trouble doing the same thing. We were really trying to help the Bahais do in a very short time what American native speakers struggle with under normal circumstances.” Compounding the students’ academic burden were the logistical challenges that come with attending an online university in a country where the ruling mullahs regularly restrict Internet access to crack down on dissent.

The students’ own daily lives, too, were frequently troubled by dint of their membership in an outlawed faith group. “We didn’t discuss” their political challenges, Dashti-Gibson told me. “It’s very sensitive.” The security of the institute’s online-learning platform, protected by password, has been repeatedly breached by the regime, shutting down access and compromising the secrecy of students’ identities. But Sabet says the Bahai institute has always been able to restore operations. During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the “reformist” government of President Mohammad Khatami for the most part neglected the institute—despite awareness of its existence. Yet even during that period, intermittent crackdowns continued.

I was born in Iran and spent the first 13 years of my life there, so the institute’s educational successes strike me as near-miraculous. I spoke (appropriately, via Skype) with Niknaz Aftahi, a 2010 graduate who recently immigrated to California and who embodies the power and promise of her alma mater. In 2005, when Aftahi graduated from high school, Iran was at the tail end of a period of relative openness. Under international pressure, the regime was for the first time permitting Bahais to take the national college-entrance examination. A handful of students were admitted and actually managed to obtain degrees. Others were allowed to enroll only to be expelled during their first or second semesters; some were expelled just as they neared graduation. The vast majority, however, had their examinations returned unscored or scored “zero.”

Aftahi was in the last group. Undeterred, she immediately set to work preparing for the institute’s own rigorous entrance examination. Initially she was interested in computer science but then decided to pursue a degree in architecture. To switch to the architecture program, she had to take additional examinations in art history, perspective, and the elements of design. Aftahi and seven other students eventually formed the inaugural class of the institute’s architecture program. “Studying architecture through distance learning was initially very difficult,” she told me. “Learning architecture requires one-on-one interaction, hours in a studio, and site visits.” But thanks to the mentorship of a renowned Bahai architect, as well as a few non-Bahai practitioners willing to lend them studio space, Aftahi and her friends had many of the learning experiences associated with a traditional program.

Since arriving in the United States, Aftahi has worked at several architectural firms in San Diego. Today she is applying to M.A. programs in architecture—a process that poses its own challenges for institute alumni. Of the 12 top-tier universities Aftahi has applied to, only one—the University of Texas at Austin—formally recognizes the Iranian program’s degrees. To gain admission to the rest, Aftahi must meet individually with admissions deans and explain her unique circumstances.

Even so, awareness of young Bahais’ plight is growing among higher-education officials in the West. More than 65 Western universities have already admitted alumni of the institute to their graduate programs. And last December, 48 deans of U.S. medical schools, led by Philip A. Pizzo, dean of Stanford University’s School of Medicine, signed a letter urging Iranian authorities to repeal their viciously discriminatory policies toward the country’s Bahais.

If recent developments are any indication, however, such pleas will fall on deaf ears. Last May, Iran’s theocrats renewed a crackdown, initially begun in the late 1990s, against the Bahai institute. They arrested a number of community leaders associated with the college and tried them on the usual, spurious charges leveled against dissidents and free thinkers in Iran, including “espionage for Israel.” They also raided several private homes where institute records, equipment, and instructional materials were stored. Last fall, Branch 28 of Tehran’s Revolutionary Court handed down four- and five-year sentences to the leaders involved. Among those detained was Riaz Sobhani, a civil engineer whose son Naim works as a senior executive with an American automobile retailer.

“My father was doing nothing but helping young people who are otherwise completely deprived of opportunities to succeed,” Naim, who was himself arbitrarily detained several times on account of his faith before immigrating to America, told me. “It is a terrible disaster. I was a little kid when the revolution happened, and our lives were turned upside-down. Then gradually things got a little bit better, and now all these nightmares are coming back.” Naim’s sister, Jinous, who studied law with the institute, has also been arrested several times and spent months in solitary confinement for having worked with the Nobel laureate Shirin Ebadi’s Defenders of Human Rights Center. “The last time they released her,” Naim told me, “they made her sign a statement saying she would desist all human-rights activity in Iran.”

Despite its uncertain future and the regime’s ever-tightening noose, the institute’s faculty will press on. “This is a matter of principle for the Bahais,” Sabet, the longtime associate, told me. “They have no other choice. Public employers do not hire them, and the private sector is closed off as well. The BIHE is the only hope they have.”

First published in The Chronicle of Higher Education.

AUTHOR

Sohrab Ahmari, an Iranian-American journalist and a nonresident associate research fellow at the Henry Jackson Society, is co-editor of Arab Spring Dreams: The Next Generation Speaks Out for Freedom and Justice From North Africa to Iran, a forthcoming anthology of writings by young Mideast dissidents (Palgrave Macmillan, 2012).