Everything is going

to be fine Everything is going

to be fine

Excerpt

March 29, 2005

iranian.com

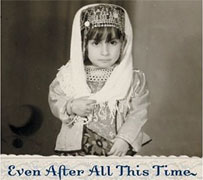

From Afschineh Latifi's Even

After All This Time: A Story of Love, Revolution, and Leaving

Iran (HarperCollins, 2005), "an immigrant saga unlike

any other. It is the story of a self-made man and the schoolteacher

with

whom he fell in love, of a family torn apart by war and violence,

and of the two little girls who found themselves on their own

in America, forced to become strong young women before they even

had a childhood."

Chapter One : The Arrest

On February 13, 1979, my father, Colonel Mohammad Bagher Latifi,

was detained at his barracks in the Farah Abad section of Tehran.

A group of enlisted men stepped into his office, relieved him of

his weapon, and informed him that he was under arrest. Less than

an hour later, three men arrived at the barracks, escorted my father

into the back of an open jeep, and drove away.

As the jeep approached the main gate, on its way out of the facility,

my father asked if he could leave his house keys behind for my

mother. The jeep stopped in front of the kiosk, and my father turned

to the guard. "Please," he said, pressing the keys and

his checkbook into the man's hands, "give these to my wife

when she comes to fetch me."

The guard took the items, and the jeep pulled away.

When my mother arrived that afternoon, the guard told her that

her husband had been taken away. She wanted to know who had taken

him and why, but the guard shrugged and pursed his lips. He did

not know, he said apologetically. He knew nothing. But he had two

items for Khanoom Sarhang, Mrs. Colonel. He turned and retrieved

the keys and the checkbook and put them into my mother's shaking

hands, and she thanked him and drove home to tend to her four children.

At dinner that night, my older sister, Afsaneh, asked about my

father, and we were told that Baba Joon was away on military business.

This was not unusual, so we sat down to eat, oblivious, and we

went to bed that night, still oblivious.

The next day, my mother drove from one Tehran jail to the next,

looking for my father, and everywhere she went she was met with

insults and abuse. "Look at you, you filthy slut! Have you

no self- respect? Can't you dress like a decent woman?"

My mother had never worn a chador in her life -- she was a thoroughly

westernized Iranian: her head exposed, a hint of make up on her

eyes and lips, even a full- time job -- but with the Shah recently

deposed and Ayatollah Khomeini newly in power, the country was

in upheaval.

"Please," she begged. "His name is Latifi, Sarhang

Latifi. If you would just let me know he's here, it would mean

the world to me."

"You are wasting your time," she was told. "We've

probably executed him already."

The next day, she tried again, crisscrossing the city, driving

from one prison to the next, but there was no sign of him, only

more insults and abuse. And when we returned home after school,

she was still out in the streets, searching, and her sister, Mali,

was waiting for us by the front door.

"Where's Mommie Joon?" I asked.

"She's running errands," Khaleh Mali said. "She'll

be back later."

I turned to look at Afsaneh. We both knew something was very

wrong.

That night, we confronted our mother, asking her to tell us the

truth. Afsaneh was eleven years old; I had just celebrated my tenth

birthday.

"Baba has been arrested," she told us. "But it's

okay; it's nothing to worry about, just a little misunderstanding.

Still, you mustn't tell the boys. They are too young. They might

get upset."

I had never seen my mother cry, and she didn't cry then, either.

But she came close. I had never seen my mother cry, and she didn't cry then, either.

But she came close.

"So where is he?" I asked.

"I don't know," she said. "They're holding him

somewhere. I'm still looking."

Afsaneh fell apart -- she was very close to Baba -- but I tried

to be strong.

"Maybe I can help you find him," I said. "I'll

go with you tomorrow, and we'll look together."

My mother's eyes grew moist, but still she didn't cry. "I

don't want you girls to worry," she said, her voice harsher

than usual to mask the pain. "Everything is going to be fine."

The next day, when I got out of school, my mother was waiting

for me on the sidewalk. She had decided to take me up on my offer,

hoping the authorities might take pity on a child. I felt like

crying -- I often cried over little things, like being late for

school or misplacing one of my dolls -- but I didn't cry this time.

I knew my mother needed me, and I was determined to make myself

useful.

For the next two days, we drove from prison to prison, searching

for my father.

"Look," she would tell the guards, pointing at me. "He

has children. There are three others at home. We are just normal

people, like you." But they showed no mercy.

When we arrived home that night, my aunt suggested that we broaden

our search. She had heard from friends that many of the more important

prisoners were being kept in government buildings, and that some

of the religious schools had been transformed into holding facilities.

The next day, after class, my mother was again waiting for me

in the street, and we tried anew. We visited half a dozen government

buildings and another half- dozen schools with no luck. However,

at our last stop, one of the guards took pity on us. He told us

to try Madrese Alavi, one of the city's better known religious

schools. "Many of the key people are there," he said.

I was exhausted and hungry, my feet hurt, and I didn't want to

go. I was unable to get my young mind around the gravity of the

situation, but my mother insisted. "This is the last place," she

said. "I promise. Then I will get you a new Barbie."

That was different! A Barbie doll! I would do it for a new Barbie!

We drove to Madrese Alavi, and my mother left me in the car,

near the entrance. The school had been turned into some sort of

provisional headquarters, and members of the new regime were everywhere.

I could see my mother at the front entrance, talking to two guards.

" Five days already?" they said, laughing. "It

would be a miracle if he was still alive."

The foregoing is excerpted from Even

After All This Time by Afschineh

Latifi. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be used or

reproduced without written permission from HarperCollins Publishers,

10 East 53rd Street, New York, NY 10022

|