|

|

Dark emerald November 23, 2001 A bitter November wind blew across the vast courtyard of the British Museum sending a few orange leaves into the air. A dozen tourists stood shivering on the steps of a genuine Simplon-Orient-Express voitures-lits that inspired one of Agatha Christie's most famous novels and film. It was almost half-past-four in the afternoon and my wife was anxious not to miss the exhibition.

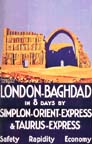

Room 5 stood adjacent to a vast gallery of giant Babylonian, Median, and Persian statues peering down on us from several hundred centuries. Our visit started uneventfully as we went inside, briefly stopping by at the museum shop. Then as if lured by magic we followed the sounds drifting from the labyrinth: jazz music, laughter, the chuff chuff of a train's engine, the voice of a commentator and at the end the piercing chant of a muezzin. Trains have always been one of my favourite things. For me the idea of creative heaven is to sit in a comfortable compartment with a good book, pen and notepad in case I'm struck with inspiration. But more interesting than that is the level of dialogue and the interesting, even strange characters that often show up on the train. In the antechamber where a short film was playing was a large map tracing the famous train routes that connected the great cities of London, Paris, Venice, Istanbul, Damascus and Baghdad. One rare poster that caught my attention depicted the Sassanian arch at Ctesiphone near the capital of modern Iraq. The caption beneath read: "London-Baghdad In 8 Days By Simplon-Orient-Express & Taurus Express: Safety, Rapidity, Economy."

The couple had lived in Baghdad and had loved it. The more they talked about the city the more fascinated she had become so much so that when they proposed she travel by the Orient Express Agatha had, the next morning, rushed round to Cook's, cancelled her tickets for the West Indies, and instead got tickets and reservations for the journey to Mesopotamia determined to find herself and all the pleasures of the unknown. From Baghdad where she stayed a few days she travelled on to Ur, to Leonard Woolley's excavations, widely publicised in England at that time. Woolley's wife, Katherine, was a fan of Agatha's writing and together they explored the desert. "The lure of the past came up to grab me," Christie wrote in her autobiography. "To see a dagger slowly appearing, with its gold glint, through the sand was romantic." Agatha fell in love with Ur, with its beauty in the evenings, the ziggurat standing up to the moon, faintly shadowed, "and that wide sea of sand with its lovely pale colours of apricot, rose, blue and mauve changing every minute."

Of her stories Christie always said that, while her characters were fictitious, the settings were real and some of her plots and characters were based loosely on experience and imagination. When Agatha rejoined Max in the following spring she arrived in the middle of a dust-storm. Unfortunately, the exhibition which concentrated on the couple's Mesopotamian digs in far-flung places such as Nimrud, Nineveh and Ur between 1930 and 1958, had omitted an important part. In 1931, when the season's expedition came to an end, Max and Agatha decided to go home by way of Persia on a brief honeymoon. There was a small air service (German) which had just started running from Baghdad to Persia. Boarding a single-engined machine, with one pilot, they flew to Hamadan, then to Tehran. From Tehran they flew to Shiraz. Being a Shirazi myself I must admit that the discovery of this fact has always made me proud for she too was enchanted by my beloved city. "I remember how beautiful it looked like a dark emerald-green jewel in a great desert of greys and browns," she wrote. She praised the gardens and the desert. While in Shiraz, Max and Agatha visited a beautiful old house where the rooms had various pictures painted in medallions on the ceilings and walls. So enamoured did she become of this house probably Qavam's Narenjestan that she was to return two more times to Shiraz in search of it and when she found it she was disappointed. The house was already dilapidated and abandoned, but it was still beautiful, even if dangerous to walk about in. She used it as the setting for a short story called, "The House at Shiraz" with a mad English woman and her dead servant among her characters.

Agatha Christie as the exhibition revealed was influenced by time and place. She was also a keen photographer shooting pictures with her Leica camera from the balcony of her suite at the Winter Palace in Luxor. A chance meeting with Howard Carter who discovered Tutankhamun's tomb and the ruins at Karnak in Egypt left a deep, eerie impression on her writing, even inspiring her historical play, Akhnaton (1937). Max returned to the Middle East after the Second World War with Agatha at his side and in 1949 she wrote, "They Came to Baghdad" published two years later while sitting on a terrace of the house belonging to the British School of Archaeology in Iraq. The main character of this bestseller was an absent-minded archaeologist that leaves no doubt to the reader whom she meant. Max Mallowan's dig in Nimrud lasted until 1958 when he returned to England. After his retirement from the field Max took up writing about his discoveries in Iraq and Iran. More importantly, I learned, he had founded the British Institute of Persian Studies in 1962. As a result he made numerous visits to Iran and worked closely with British and Iranian colleagues in Tehran, something that did not go unnoticed by the Shah of Iran. Among the surprises in Room 5, were two medals from Iran and a letter from Buckingham Palace dated 8th December, 1977. It read: "Sir, I have the honour to inform you that the Queen has been graciously pleased to grant to you unrestricted permission to wear the insignia of Order of Homayoon, Class 2, which has been conferred upon you by His Imperial Majesty, Mohammed Reza Shah Pahlavi Arya Mehr, Shahanshah of Iran in recognition of your services." While Agatha continued to enjoy her success as one of the world's most famous crime writers, Max went on to teach at Oxford. He was knighted in 1968 and in 1973 he was appointed a Trustee of the British Museum. Towards the end of the exhibition a certain sadness had taken over as we read how in her last years Dame Agatha had led a modest life, living quietly and privately, enjoying books, music, flowers, her house in South Devon, garden and friends. She died on 12 January 1976 at Winterbrook, just after luncheon, and was buried in the churchyard at Cholsey, nearby. Her death left Max with "a feeling of emptiness after forty-five years of a loving and merry companionship." In September 1977 Max Mallowan married his old friend Barbara Parker who had been the epigraphist at Nimrud. He died the following year on 1st August 1978.

Outside the museum in the main courtyard, my wife Shuhub and I toured the inside of the voitures-lits and marvelled at the exquisite compartments of the Orient-Express train promising each other a trip one day on the real thing. Later on the way home we imagined our own personal travels from our sunny childhoods in Shiraz and Baghdad to another existence in London. We recalled how we had fallen in love among the Babylonian and Persian statues in the British Museum. We talked about the past and how once we had wanted to be archaeologists and how despite this unfulfilled dream we still longed to revisit our lost cities. We imagined a day when we would stroll together among the eternal ruins of Persepolis and Ctesiphon. Then the words of Agatha Christie haunted us. "Never," she warned, "go back to a place where you have been happy. Until you do it remains alive for you. If you go back it will be destroyed."

|

|

|

Web design by BTC Consultants

Internet server: Global Publishing Group

Holding on to her gloved hand she rushed me up the stairs.

We crossed the marbled hall and bought our tickets at the Great Court. The

exhibition, created by Dr. Charlotte Trumpler of the Ruhrlandmuseum, Essen,

and the family of the famous crime writer and her archaeologist husband,

was located in Room 5 in the West Wing Exhibition Gallery. To get there

we had to pass through a narrow corridor where Peter Ustinov's white linen

suit used in the film "Death On The Nile" hung majestically in

front of an enlarged photo of an Egyptian sunset complete with feluccas

sailing down river.

Holding on to her gloved hand she rushed me up the stairs.

We crossed the marbled hall and bought our tickets at the Great Court. The

exhibition, created by Dr. Charlotte Trumpler of the Ruhrlandmuseum, Essen,

and the family of the famous crime writer and her archaeologist husband,

was located in Room 5 in the West Wing Exhibition Gallery. To get there

we had to pass through a narrow corridor where Peter Ustinov's white linen

suit used in the film "Death On The Nile" hung majestically in

front of an enlarged photo of an Egyptian sunset complete with feluccas

sailing down river. In the autumn of 1928, at the age of thirty-eight, Agatha Christie,

recently divorced from her estranged husband and writing for a living, was

at a low point in her life, and in need of a holiday. As she boarded the

Orient Express for the first time she was unaware how the journey would

change her life so entirely. Five days before leaving London, Agatha had

been introduced to a naval officer and his wife over dinner at a friend's

house.

In the autumn of 1928, at the age of thirty-eight, Agatha Christie,

recently divorced from her estranged husband and writing for a living, was

at a low point in her life, and in need of a holiday. As she boarded the

Orient Express for the first time she was unaware how the journey would

change her life so entirely. Five days before leaving London, Agatha had

been introduced to a naval officer and his wife over dinner at a friend's

house. In the spring of 1930 Agatha took up Katherine's invitation

and returned to Mesopotamia where she met Max Mallowan, an archaeologist

fifteen years her junior. They seemed to hit it off and soon afterwards

they were married in England. Life with Max took Agatha to worlds she had

not known and in Room 5 my Baghdad born wife pointed at the notebooks and

letters and novels exhibited around the place showing how stimulating Agatha

had found these new experiences.

In the spring of 1930 Agatha took up Katherine's invitation

and returned to Mesopotamia where she met Max Mallowan, an archaeologist

fifteen years her junior. They seemed to hit it off and soon afterwards

they were married in England. Life with Max took Agatha to worlds she had

not known and in Room 5 my Baghdad born wife pointed at the notebooks and

letters and novels exhibited around the place showing how stimulating Agatha

had found these new experiences.

It was half-past five and as we came to the end of the exhibition

it was clear to my wife and I that the contents of Room 5 with its wide

range of objects over 200 including diaries, photos, Hollywood sketches

of costumes for movies based on her novels, and previously unseen films,

shot by Christie herself, had revealed a unique personality who had combined

writing with the reality of archaeological excavation and oriental travel.

Agatha Christie as far as we were concerned had in her lifetime held a certain

dialogue with civilizations different from hers and yet rooted in antiquity

and humanity.

It was half-past five and as we came to the end of the exhibition

it was clear to my wife and I that the contents of Room 5 with its wide

range of objects over 200 including diaries, photos, Hollywood sketches

of costumes for movies based on her novels, and previously unseen films,

shot by Christie herself, had revealed a unique personality who had combined

writing with the reality of archaeological excavation and oriental travel.

Agatha Christie as far as we were concerned had in her lifetime held a certain

dialogue with civilizations different from hers and yet rooted in antiquity

and humanity.