Beedaarsheed Beedaarsheed

A modern geopolitical primer for Iranian expatriates

Ramin Davoodi

February 16, 2005

iranian.com

Q. What would

you do if Congress embargoes arms sales in the Persian Gulf region?

A. That would be so irresponsible that I am not even thinking

about it. But if it happens, do you think our hands are tied?

We have ten other markets to provide us with what we need. There

are people just waiting for that moment.

If you remain our friends, obviously you

will enjoy all the power and prestige of my country. But if

you try to take an unfriendly

attitude toward my country, we can hurt you as badly if not

more so than you can hurt us. Not just through oil - we can

create

trouble for you in the region. If you force us to change our

friendly attitude, the repercussions will be immeasurable. --

Mohammad-Reza Shah Pahlavi, U.S. News & World Report,

March 22, 1976.

Iranians in America are

starting to wake up to the palpable sense of danger facing their

homeland. This danger isn't limited to just the very real

sense of a potential physical encroachment by an outside state;

it is all the more felt, as it has been in decades past, in the

imminently humiliating context of a loss of vital state sovereignty

at the hands of larger, more aggressive powers.

Recent statements

made by US Vice President Dick Cheney and Secretary of State

Condoleezza Rice, alluding to the perceived need for confronting

Iran over its alleged nuclear activities, lack the normal "spin"

quotient accompanying much of what the Bush Administration emotes

regularly

regarding its foreign policy.

This is so because said statements

accompany reports of alleged reconnaissance missions being

flown over Iran, as well as the infiltration of Iran by US-hired

or

appointed intelligence operatives ranging from Mujahedin-e

Khalq Organization (MEK or MKO) members, to European Union passport-carrying

business vendors, to seemingly meandering expatriots who make

a point of traveling to and from Iran annually.

For many Iranians

abroad who desire to see Iran ultimately change into an Open

Society, building feelings of anticipation, nay, elation, over

impending

changes are mixed with and trepidation, concern and a demonstrably

justifiable sense of anxiety.

Yet what exactly is imminent? Has the Iranian community collectively

considered and consulted over the implications of any show of

violence towards, or in, Iran in this day and age? Or are we so

inebriated with a half-witted sense of anticipation over seemingly

epochal changes on the one hand, and the maddening general pace

of life in the West on the other, that world events guided by

other parties must, yet again, tragically visit themselves on

our homeland and core culture?

Are we aware of the fact that Iran

represents an increasingly valuable and indispensable pivot

point in the modern global geopolitical and economic landscape,

or do

we, too, buy into the convenient media-issued image of Iran

as just another corrupt domino that must fall to the "democracy"

exporting

Neoconservative juggernaut which stretches from San Diego to

Washington, London and Tel Aviv?

Considering the dizzying global economic stakes that both the

US and Iran face in this day of dissipating petrochemical reserves,

shifting strategic alliances, precarious global finances, rising

regional instabilities, diverging demographic trends and mounting

environmental havoc, it is best that the expatriated descendents

of Darius, Kourosh and Cyrus the Great take adequate note of various

realities on the ground in Iran and Asia.

Oil, Trade, Leverage and Other Geopolitical Realities

Iran retains the second largest bed of natural

gas in the world and 10% of the globe's oil reserves. In a world

where demand

for energy resources have started to outpace supplies (discovered

or undiscovered) over the past few years and oil reserves are

dissipating in a scenario known as "Peak Oil" , these

are not insignificant facts.

The current leadership in Iran certainly

recognizes these facts and has reacted to them, as well as to

the political pressures placed on it from the "Coalition

of the Willing", partly by tactically positioning itself

alongside other strategically valuable powers which are in need

of vital energy resources.

Iran recently signed a $100 billion

oil and natural gas deal with China that will be reciprocated

with Chinese goods and services. China has the fastest economic

growth rate -- and thus, need for oil -- in the world.

China also retains a crucial United Nations Security Council

vote/veto, which could prove valuable to Iran should the UN be

urged to impose

widespread economic sanctions on Iran by the US, Israel or even

European states.

Iran also recently announced a strategically crucial $40 billion

natural gas deal with India that garnered the blessings of China,

Japan and South Korea. Such a project would ultimately necessitate

a pipeline to be built across India's arch-rival nation

of Pakistan. Iranian-Pakistani relations have strengthened after

the fall of the Taliban in neighboring Afghanistan and frequent

reciprocal visits have been made by senior officials.

Although

in very preliminary stages, this deal in part reflects Tehran's

growing diplomatic ambitions -- through energy sharing, Iran

could link these two historic enemies' economic interests. The

US naturally opposes such a deal and is pressuring both Pakistan

and India to reject it. According to the Asia Times, such a

deal,

if implemented, would also "foreclose whatever prospects

remain of the revival of the trans-Afghan pipeline project,

which many still see as a raison d'etre of the US intervention

in Afghanistan."

Despite

Pakistan's current alliance with the US, such economic and

diplomatic actions by Iran present the possibility that, were

the US or Israel to attack Iran, they would further alienate

Iran's Muslim neighbor to the east from the US by drawing the

Karachi

street's sympathies, pressuring Musharraf and threatening

Pakistan's client-state status for the West.

To Iran's northeast is Russia, which has been collaborating

with Iran in oil and natural gas production, nuclear energy, civic

infrastructure and transportation development. The increasingly

(and justifiably) paranoid and power consolidating Vladimir Putin

is fighting off US and Israeli assertions on Russia's inherent

energy riches with actions ranging from the jailing of ambitious

American-Israeli leaning oil tycoon Mikhail Khodorkovsky , to

trying to deflect the possibility of a strategic loss of Ukraine

from Russia's sphere of influence (thus far, Putin has batted

.500 over these two goals).

With US overtures towards Eastern

Europe, the foreign-assisted procurement of a US-friendly government

in Ukraine , meddling in Kiev, as well as US Defense Secretary

Donald Rumsfeld's recent visits to the former Soviet states

near the Caspian Sea , it is safe to say that Moscow is not

about to lose Iran as well to the US, UK and Israel.

Some modern history is in order with regard to the US, Russia

and Iran. In 1978 and 1979, the Shah of Iran initially faced increasing

pressures from a restless population and eventually, a mass revolt

that ousted him and seized the US Embassy. An itchy Carter Administration

wished at one point to use outright force to put down the Iranian

insurrection. The US hesitated and finally refrained from doing

so, due in large part to heavy admonitions from Soviet Premiere

Leonid Brezhnev, who claimed that US intrusion into Iran would

be received as an act of aggression against the Soviet Union's

interests.

According to author Larry Everest, Brezhnev "warned

the US that ‘any interference, especially military, in the

affairs of Iran, a state which directly borders the Soviet Union,

would be regarded as affecting its own security,' thereby

raising the specter that the Soviets could invoke the 1921 treaty

giving them the right to move troops into Iran in the event of

foreign armed intervention. The US replied that it would not interfere,

weakening the Shah's regime and bolstering its opponents." Tensions

between the US and the Soviets continued into 1980, during and

after the failed hostage rescue mission that was attempted by

the Carter Administration.

The same sentiments emanate from a steely-eyed Moscow today,

with Duma member and Head of Iran-Russia Parliamentary Friendship

Committee Youri Savilov stating last year that the "threats

by the U.S. and Israel against Iran contravene international law",

and announcing that "Moscow and Tehran have recently signed

a 10-year economic cooperation agreement." Russian Foreign

Minister Sergei Lavrov also recently praised "prospects

for Russian-Iranian relations. Iran is our neighbor and our traditional

partner."

For the sake of at least political fluency, Iranian expatriots

must awaken to the fact that the various powers surrounding Iran,

including China, Pakistan, India and certainly Russia, are against

US / Israeli attempts at an overt attack, invasion or covert regime

change in Iran. Some of these powers may therefore understandably

react under such circumstances to protect their own growing strategic

and economic interests in Iran.

The Wider Picture, The Larger Stakes

The US and Israel desire immediate regime

change in Iran. They claim that, due to Iran's history of supporting

terrorism,

its meddling in Iraq's current state of affairs, and its

ambitions to develop nuclear weapons, that ideally Iran and the

world would benefit from a change in government. Yet why now are

these powers so adamant about regime change in Iran, versus during

the 1990s or even before that?

The answer may lie behind the fact

that they realize, as does the rest of the world, that Iran

is ambitiously seeking to assist in the sweeping yet controversial

reordering of global energy pricing and trading rules that is

now in procession. Iran's perceived need to defend itself

would then be triggered, in turn, by threats against its sovereign

right for seeking such tectonically sweeping economic ambitions.

Certainly, the prime reasons stated in the press for the US

to confront Iran involve the possibility that Iran is developing

a nuclear arsenal. Although the Iranian government, as well as

the Russian government which is largely responsible for the materiel

sold to Iran, deny that such nuclear intentions exist, any nation

in Iran's surrounded and threatened condition would be acting

irrationally if it weren't seeking to develop a viable deterrent

against foreign aggressions. So, regardless of any or our particular

political leanings or beliefs and for the sake of argument, let

us assume that Iran is indeed developing an atomic weapon.

Said powers who have signed massive energy deals with Iran,

or who have concurred with such economic agreements, have done

so with the hope of eventually altering or overturning the longstanding

US petro-dollar hegemony that has had large energy producing nations

over a barrel for decades (so to speak).

Arguably, unhindered

access to abundant flows of oil underwrites modern capitalism.

However, there is a widely held perception that a global energy

crisis is approaching due to dissipating oil and gas resources

and exponentially rising demand for said resources. Additionally,

the areas with the largest deposits of petrochemicals and hydrocarbons

on earth have also been some of the most politically unstable.

Under such a combined scenario of increasing resource scarcity

as well as political instabilities surrounding oil-rich regions

of the earth, nations with military might will expectedly

assert themselves and their economic agendas -- the US being

the

prime example of this phenomenon. American authors and investment

advisors Stephen and Donna Leeb recently outlined the relationship

between oil, capitalism and the need for military might in

a much more candid manner than either the mainstream American

press,

or certainly the Bush Administration, have done:

As worldwide oil supplies grow scarcer, and as large areas

of the world, such as China, continue to industrialize, meaning

they become ever more avid consumers of energy, countries will

be competing

with one another to buy the oil their economies require. This

is a big change, and countries that have no means of throwing

their weight around will lose out. For the U.S., military

might

is the ace in the hole that will ensure that we have access

to diminishing supplies of oil - that our allocations receive

favorable

treatment from oil producers....

If all we had to worry about were essentially political crises,

we could maintain and upgrade our military capability at a relatively

moderate level and still have the power and flexibility we need.

It's the looming energy crisis that suggest we will need to

build up our defenses at an accelerated pace....

To understand why energy and defense are so closely linked,

consider the fact that almost all the oil in the world is produced

in economically underdeveloped and hence intrinsically unstable

countries. We're not talking only about Middle Eastern oil producers,

thought they obviously fit the bill. We're also thinking of

such countries as Venezuela and Nigeria. In other words, our

economy's

lifeblood depends on an assortment of volatile countries with

relatively immature economies....

The U.S. will need the ability to intervene militarily, or

to plausibly threaten to do so, in the event of any major disruption

in any oil-producing country....

To the extent that [the oil producers'] economies become more

developed, they will need to use more oil themselves, and the

amount of oil they are willing to export will shrink. It's not

inconceivable that at some point we'll be implicitly relying

on overwhelming military might to ensure that they continue

to export

what we need.

[Stephen and Donna Leeb, The Oil Factor: Protect Yourself

and Profit from the Coming Energy Crisis Pages 161-164,

Time Warner Book Group (copyright 2004)]

An astonishing level of clarity is provided here,

all the more so because this information is written in an

investment guide rather than a book written on political, economic

or strategic

issues, per say. Such an energy-focused bottom line was given

as well a few years ago by former CIA agent and advisor to

President Clinton, Kenneth Pollack:

"It's the Oil, Stupid - The reason the United States

has a legitimate and critical interest in seeing that Persian

Gulf oil continues to flow copiously and relatively cheaply

is simply that the global economy built over the last 50 years

rests

on a foundation of inexpensive, plentiful oil, and if that

foundation were removed, the global economy would collapse."

Further proof of the dissipating state of global oil came in

a report submitted on behalf of former Secretary of State under

George H.W. Bush, James Baker: "[T]he world is currently

precariously close to utilizing all of its available global

oil production capacity, raising the chances of an oil supply

crisis

with more substantial consequences than seen in three decades."

So, be that as it may, it is undeniable that the US has invaded

and occupied Iraq due to its core energy and strategic interests,

rather than for the reasons stated by the Bush Administration.

Anyone still in doubt over this reality should consult the same

US government appointed mid-2001 energy task force report quoted

above on the dangers of a then increasingly wily Saddam Hussein:

[Tight oil] markets have increased US and global vulnerability

to disruption and provided adversaries undue potential influence

over the price of oil. Iraq has become a key 'swing' producer,

posing a difficult situation for the US government ... Iraq

remains a de-stabilizing influence to ... the flow of oil to

international

markets from the Middle East. Saddam Hussein has also demonstrated

a willingness to threaten to use the oil weapon and to use his

own export programme to manipulate oil markets. [Strategic

Energy Policy Challenges For the 21st Century, Report of an Independent

Task Force, Sponsored by the James A. Baker Institute for Public

Policy. Emphasis mine]

Saddam Hussein switched his energy trading currency standard

from dollars to euros as early as 1999, finally solidifying the

arrangement in 2002. He thereby sealed his fate with the US and

its "coalition", who wished to send a stern warning

to any other energy producer, OPEC member or otherwise, that such

manipulation with the longstanding petro-dollar arrangement would

be met with staunch resistance by the US.

However, not all of the other large energy producers, and certainly

not Iran, are as politically fragmented and economically dilapidated

as was Iraq after it sustained two decades of sanctions and war.

OPEC member Venezuela has also committed to such a currency move,

expectedly drawing the ire of the US. Further, according to the

Financial Times of London, Venezuela very recently enrolled Iran,

its "closest ally in OPEC", in accelerating "a

strategy to steer its oil exports to China and away from its traditional

market of the US."

There are massive global economic stakes behind Iran's

future economic direction and who will ultimately govern it. The

US wishes to prevent Tehran from setting an energy course of its

own accord. Period. It ultimately does not matter to the US government

what form of regime occupies Tehran as long as Iran does not run

counter to America's energy and strategic interests. Despite

decades of following this edict tacitly, the US officially codified

it in 1980 with the Carter Doctrine which declared, in response

to the Soviet occupation of Afghanistan and the Revolution in

Iran, that the secure flow of Persian Gulf oil and natural gas

was in "the vital interests of the United States of America." In

protecting such interests, the US would use "any means necessary,

including military force."

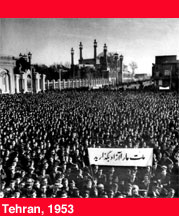

By signing sweeping energy deals with larger Asian nations,

as well as joining a widening global consensus that is leaning

away from default US dollar hegemony, Iran is once again attempting

to set its own economic course. This course in large part results

from Iran's Nationalistic instincts, as it had in the 1950s

and mid 1970s, yet also reflects a necessarily evolving sense

of global economic interdependency and cooperation against the

backdrop of falling global oil supplies and skyrocketing demand

for those supplies. As stated recently in the Asia Times:

The drive for resources is occurring in a world where alliances

are shifting among major oil-producing and consuming nations.

A kind of post-Cold War global lineup against perceived US hegemony

seems to be in the earliest stages of formation, possibly including

Brazil, China India, Iran, Russia and Venezuela. Russian President

Vladimir Putin's riposte to a US strategy of building up

its military presence in some of the former [Soviet Socialist

Republic nation-states] has been to ally the Russian and Iranian

oil industries, organize large-scale joint war games with the

Chinese military, and work toward the goal of opening up the

shortest, cheapest, and potentially most lucrative new oil route

of all,

southward out of the Caspian Sea area to Iran. In the meantime,

the European Union is now negotiating to drop its ban on arms

shipments to China (much to the publicly expressed chagrin of

the Pentagon). Russia has also offered a stake in its recently

nationalized Yukos (a leading, pro-Western Russian oil company

forced into bankruptcy by the Putin government) to China.

[Michael T. Klare, The oil that drives the US military, Asia Times online, 10.09.04.]

With this wider picture of Russian, Chinese, Venezuelan, Indian,

Pakistani and even European symbiotic involvement in Iran's

economic and diplomatic ambitions, one wonders if the US plans

to, or even can, use such implied means in defending its energy

interests in the manner outlined by both the Carter Doctrine as

well as by the half-century of general US strategic policy in

the Middle East.

A significant portion of US interests involve

keeping the pricing and trading of energy resources, and thus

the functioning of the general global economy, anchored to the

US dollar standard. Indeed, the stakes have never been higher

for the US economically, or for the world. America's massive

and growing account and trade deficits, along with its Himalayan-sized

national debt totaling $7.6 trillion , threaten its economy, the

global economy, and certainly the dollar's global reserve

currency role. "Never before has the guardian of the world's

main reserve currency been its biggest net debtor," proclaimed

The Economist recently.

As a result of these

systemic fiscal predicaments, the US Federal Reserve is cornered

and limited in its choice of actions with regard to available

monetary and fiscal policies. The dollar is dropping in value

against other currencies because the US has no other choice

-- it must devalue its currency, while concurrently raising interest

rates, in order to spark foreign demand for its products while

simultaneously preventing a flight on the dollar by foreign

central

banks (who have overwhelmingly replaced foreign private investors

as the main purchasers of US Treasury bonds over the past four

years). The US finances its deficits by issuing credit to such

an extent that a credit bubble is forming, posing grave deflationary

pressures for the global economic system which is (thus far)

so dependent on the US economy. As a result of these

systemic fiscal predicaments, the US Federal Reserve is cornered

and limited in its choice of actions with regard to available

monetary and fiscal policies. The dollar is dropping in value

against other currencies because the US has no other choice

-- it must devalue its currency, while concurrently raising interest

rates, in order to spark foreign demand for its products while

simultaneously preventing a flight on the dollar by foreign

central

banks (who have overwhelmingly replaced foreign private investors

as the main purchasers of US Treasury bonds over the past four

years). The US finances its deficits by issuing credit to such

an extent that a credit bubble is forming, posing grave deflationary

pressures for the global economic system which is (thus far)

so dependent on the US economy.

How is this wider, increasingly dismal economic picture related

to America's policy towards Iran? Answer: Again, safe, predictable

access to (read: control of), global petroleum and natural gas

reserves underwrite US dollar hegemony. Oil is the final arbiter

for the health of global capitalism -- a system that, despite

US Monetarist and market fundamentalist proclamations of unlimited

abundances and unhindered fiscal freedoms, is actually quite limited

by stubbornly tangible manifestations of resource scarcity.

Iran,

sitting on massive reserves of oil and natural gas, recognizes

this reality, as do the nations Iran is signing energy and cooperation

contracts with (be they tight US allies such as India, or not,

such as Venezuela under Hugo Chavez). Thus, in many fundamental

ways, the United States is much more dependent upon Iran than

the other way around. Should Iran proceed with the collective

nations' plan of prying OPEC away from the dollar standard,

something the cartel is increasingly doing on its own anyway,

this could prove disastrous to US driven market fundamentalism

and the dollar as the world's fiat currency, let alone the

obscenely over-leveraged US economy itself.

With the stakes so

catastrophically high, it is not hard to see why the US and Israel

will stop at nothing to unravel Iran, however much potential death

and destruction such an action would bring about in Iran. The

fight will thus not be for "Democracy in Iran", but

for US strategic interests, as it has been for over fifty years.

The battle will not only be against Iran's ultimate ability

to sustainably determine its own economic destiny, but against

the aforementioned global economic inertia away from a fiscally

and imperially overstretched sense of American economic and military

predominance. These are the ultimate stakes; this is the abject

reality all Iranians must face in today's tense world.

Iranians in the West are naturally against the theocratic regime

that has autocratically run Iran for over a generation -- so

much so that they are blinded to the wider, unprecedented geopolitical

and global economic picture in which Iran plays an increasingly

central part. Considering such tense stakes, Iran's inherent

Nationalism, as well as how interdependent Iran's economy

has become with those of China, India, Russia, Venezuela, the

European Union and other nations, it is not inaccurate to sense

that any show of force against Iran could be the modern equivalent

of the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand in 1914.

Expectedly,

Iranians in the West, however much they oppose the Islamic Republic,

overwhelmingly reject the option of force against Iran. Iranians

everywhere also recognize, and largely concur with, the widespread

ambition of Iran to arm itself adequately against ever again

being turned into anyone's client-state, which has been a role

assigned by larger industrial powers onto energy-resource-rich

nations in the developing world for decades (a role that seems

to keep said nations in a perpetually "developing",

rather than "developed", state). Such Iranian ambitions

existed in the early 1970s as well. In fact, the coy language

of the late Shah of Iran at that period did not differ significantly

with regard to the need and use of Iranian nuclear energy than

it does today:

Q: Do you plan to buy nuclear power plants, even a nuclear fuel

reprocessing plant, from the US?

A: I intend certainly to buy nuclear plants from the U.S. if

they are competitive with those offered by France and Germany.

On reprocessing [plants], not yet, because it is only economical

if you process large amounts. Maybe one day we shall have

so many atomic plants that we will have to do that in our own

country.

But don't forget that we signed the non-proliferation treaty,

and

when we sign something we feel obligated to it. [Mohammad-Reza

Shah Pahlavi, U.S. News & World Report, March 22,

1976.]

The Core Issue

for Iranians worldwide

Iranians must realize where the world is going economically,

acknowledge Iran's pivotal positioning in such unprecedented

changes, recall with sobriety Iran's modern history vis-à-vis

its role as a major energy producer, and then decide what's

best for Iran -- including what's best for Iranian

relations with the West.

Ultimately, when presented with the true

gravity of the situation facing their homeland, Iranians from

Westwood to London to Sydney will match in word and deed the

Nationalism of the bright, hungry and aware Iranian youth in Tehran

-- those

who realize what the stakes represent for Iran and the world.

True Iranians who show fidelity towards the enduring grandeur

of Pars

will speak through one Nationalistic Aryan voice. Ultimately, when presented with the true

gravity of the situation facing their homeland, Iranians from

Westwood to London to Sydney will match in word and deed the

Nationalism of the bright, hungry and aware Iranian youth in Tehran

-- those

who realize what the stakes represent for Iran and the world.

True Iranians who show fidelity towards the enduring grandeur

of Pars

will speak through one Nationalistic Aryan voice.

With

that said, it is best if the Iranians in the West start early

down this path and remove any blinders or preconceived notions

they may retain regarding the bottom-line positions, stated or

unstated, for the US, UK and Israel on Iran. The past demonstrably

serves as prologue on this matter.

[Text

with references] About

Author is a concerned Iranian expatriot living

in the West.

*

*

|