The next level The next level

Rafsanjani, a seasoned veteran of infighting and related

international intrigue, may be looking to make Islamic Iran

a full member of the international community

Maggie

Mitchell

June 16, 2005

iranian.com

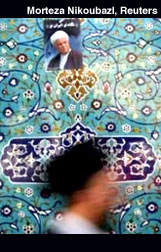

As Time Magazine put it, Ayatollah Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani

is "poised" - not guaranteed - to win a third term as

Iran's president in elections on Friday.

Given Rafsanjani's close relationship with the Islamic Republic's

founding spiritual leader Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini, a certain

capital might wince from some involuntary flashbacks.

Seared into the national conscious of those over the age of 35

are scenes of the Shah's hasty departure in 1979, and the Shi'ite

tsunami that followed the Islamic revolution. The clash of opposing

religious and political ideologies sparked a sharp up-tick in harsh

rhetoric and threats of military confrontation.

Then came the storming of the US Embassy in Tehran; diplomatic

relations severed. National pride deeply wounded; national interests

at home and in the region jeopardized.

In the Iran-Iraq war that raged for most of the 1980s, this capital

lent funds and military support to Iraq. Yet despite the very obvious

enmity, senior officials took part in a secret dialogue with Tehran

to free hostages in Lebanon.

Divisions were again exacerbated as both nations once again took

opposing sides - this time in the Middle East peace process.

By the mid-1990s, particularly after the 1997 election of moderate

Mohammad Khatami, Iran's current president, both sides seemed weary

of the fight and wary - but willing - to consider a more constructive

relationship.

Of course, oil was a critical factor in their tentative rapprochement.

But hardliners on either side remained fiercely opposed to each

other; in Iran, infighting on the domestic political front spilled

over into the foreign-policy arena. For instance, the 1996 Khobar

bombing that killed 19 Americans.

If you've conjured up the long and tortuous history of the "Great

Satan's" relationship with a charter member of the "axis

of evil", try again.

Think Riyadh.

After all, the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia has more physical proximity

to Iran than the US, and even more compelling ideological reasons

to fear the fiery, infectious pulpit-pounding export-oriented Shi'ite

orthodoxy that Khomeini championed. Iranian revolutionaries storming

the Saudis' oil-rich eastern province, inciting the Shi'ite minority

to revolt or cause mayhem (as in Khobar), and undermining their

authority as custodians of the two holiest places to all Muslims

(as in the 1987 Iranian-instigated hajj riot) pose a very credible

threat to Saudi national security.

The Wahhabis vs the ayatollahs: an unprecedented religious showdown

with long-term international implications.

But today, Saudi-Iranian relations are marked by trade delegations,

cultural exchanges and even direct flights.

While Khatemi oversaw the bulk of the reconciliation process

and its deliverables, Rafsanjani (president from 1989-97) was a

part of the initial, modest transformation during his second term

and in his post-presidential political afterlife.

In 1998, six months after he finished his second term, Rafsanjani

visited Riyadh, the highest-level official to do so since the 1979

revolution.

In 1996, the Khobar attack almost derailed the nascent detente.

Some experts believe hardliners were responsible. Despite the opacity

of Tehran's domestic politics, that reasoning has merit, particularly

in light of Saudi behavior afterward. Riyadh chose to stymie the

FBI probe, which strained normally

closely guarded relations with Washington.

Iran's ruling clerics have counted on external enemies, particularly

those who directly threaten national security - like US troop positions

in neighboring countries - to strangle internal reforms and maintain

their otherwise unpopular crackdown on civil liberties.

Washington has often played right into their hands.

Some within and around the US administration of President George

W Bush conjure up another Iranian revolution, this one to shake

off the hardliners. Bush openly calls for Iranians to rise up and

oppose their government.

Over a decade ago, Riyadh reluctantly acknowledged the enduring

power of Khomeini's founding vision.

To sort out Iran's internal scene requires omniscience - or an

embassy in Tehran. The US lacks both; but not the Saudis.

Riyadh never closed their mission - despite the revolution, Khomeini's

constant threats, and the Iran-Iraq war. Then in 1987 a mob overran

the compound, destroyed the embassy and killed a Saudi diplomat.

The mission reopened in 1991.

In the end, pragmatism won out.

Here again, the US played a role. Both capitals, and peoples,

opposed US military strikes in Iraq during the late 1990s. American

displays of hard power remain wildly unpopular.

For the kingdom, the bombing and sanctioning of Iraq raised,

yet again, the specter of a double standard: if you're Saddam Hussein,

UN resolutions apply to you; if you're Israeli prime minister Benjamin "Bibi" Netanyahu,

they don't.

For Iran, not only were the strikes morally offensive, they were

a potential military threat.

American muscle flexing in the region - including the basing

of troops in Saudi Arabia - caused considerable angst in Iran long

before the advent of Bush's policy of unilateral intervention.

Then, there was the other factor: oil.

Both sought to end the slump in oil prices. Remember oil at $15

a barrel? Analysts at the time thought a second dip was probable.

Such an outcome would have spelled economic ruin for both Riyadh

and Tehran.

Core national interests thawed the ideological freeze. That's

a valuable lesson. Both sought to end the slump in oil prices. Remember oil at $15

a barrel? Analysts at the time thought a second dip was probable.

Such an outcome would have spelled economic ruin for both Riyadh

and Tehran.

Core national interests thawed the ideological freeze. That's

a valuable lesson.

During the past decade, Washington and Tehran have shown tantalizing

signs that the vast void between them could indeed be bridged if

both put their interests before ideology.

"Crisis communication" - from the USS Vincennes felling

of an Iranian airbus to the September 11, 2001, terror attacks

to stabilizing Afghanistan to the Bam earthquake - all were opportunities

to bypass hardliners and sustain dialogue.

Former president Bill Clinton began his first term with "dual

containment" and ended his second with an appearance at Khatami's

UN speech. Khatami was not authorized to shake Clinton's hand.

The handshake came in November 2001, between former secretary

of state Colin Powell and Iran's foreign minister Kamal Kharrazi.

After September 11, Iran provided substantial assistance to the

US to defeat their common enemy - the Taliban and al-Qaeda.

Then, in January 2002, Iran's international adventurism once

again short-circuited constructive engagement. Israeli forces seized

a ship loaded with 50 tons of arms bound for the Palestinian Authority.

Both Washington and Tel Aviv accused Iran of funneling the weapons

to Islamic militants.

Less than a month later, Bush identified Iran as part of the

triple crown of evil. The relationship has failed to recover.

The slowly escalating conflict over Iran's nuclear program is

just the latest installment in an unnecessarily tortuous relationship.

What's next? There is no reason to believe that Rafsanjani will

shake off the hardliners. Some will be eager to hem him in.

The question remains: will Washington stop rewarding the hardliners'

bad behavior by engaging in direct, if carefully calibrated dialogue

with Tehran. Gary Sick, a former national security adviser who

covered Iran during the revolution and hostage crisis, had this

to say in January 2004: "I don't see any immediate or miraculous

breakthrough, where Iran and the United States embrace or set up

formal diplomatic relations. On the other hand, all it would really

take for a very rapid movement in that direction would be an expression

of will on the part of an Iranian or American leader. Up to now,

that has not been present."

Unfortunately, the deficit of determined leadership remains more

than 18 months later.

There are ample reasons to do better, roughly 34 million of them.

American values - not necessarily policies - are popular among

Iran's under 35 set, a majority of the country. Bush is right to

reach out to them. But phony broadcasting and White House entreaties

are only tactics, and weak ones at that. He could start by formulating

a strategy that pushes the right buttons in Tehran - and doesn't

push likely allies into the arms of hardliners.

Rafsanjani, a seasoned veteran of infighting and related international

intrigue, may be looking to take the revolution he helped install

and sustain to the next level: Islamic Iran as a full member of

the international community. He can't do that without Bush's consent.

And both Bush and Rafsanjani may find good reason to come together

to stabilize Iraq - most recently, the bombings in the neighboring,

oil-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan. Rafsanjani, a seasoned veteran of infighting and related international

intrigue, may be looking to take the revolution he helped install

and sustain to the next level: Islamic Iran as a full member of

the international community. He can't do that without Bush's consent.

And both Bush and Rafsanjani may find good reason to come together

to stabilize Iraq - most recently, the bombings in the neighboring,

oil-rich Iranian province of Khuzestan.

But each has to overcome enormous ideological hurdles, prolonged

historical hysteria, and deeply ingrained suspicion.

Riyadh's royal court could offer up some sober advice to Bush's

inner circle. That is, if anyone were willing to listen.

Copyright 2005 Maggie Mitchell Salem About

Maggie Mitchell Salem is a former special assistant to US

secretary of state Madeleine K Albright; a former career foreign

service

officer; former director of communications and outreach at the

Middle East Institute in Washington, DC; she now provides Middle

East analysis to private and public sector clients in the US and

the region, including a number of dailies in Arabic and English.

|