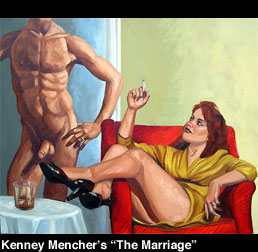

Model of love Model of love

Sexuality and marriage: What heterosexuals may be picking up from homosexuals

Hamid Karimianpour

September 20, 2005

iranian.com

It is my impression that two assumptions are deeply rooted in the way we understand our society and culture: firstly, marriage as a formalized union of a male and a female is taken to be the basic unit -- the atomic component -- which renders our society stable. Secondly, it is thought that there is no other way of organizing the society at the atomic level, i.e. family life and its sexual practices have always been and necessarily have to be the way they are today.

This article rejects both assumptions by arguing that the contemporary model of family is but a temporal occurrence in the broader historical context, which is unlikely to retain its grip for much longer.

Though marriage as a formalized institution began with the birth of ancient civilizations, it is not implausible that its foundations was already laid among the cavemen tens of thousand years ago when human sexuality differed little from that of any other primate. Male chimpanzees notoriously have to fight for the rights to copulate. It is thinkable that the cavemen behaved just in the same way. Sex for the cavemen might have been an expression of pleasure and physical dominance.

The rivalry among the early human males would have jeopardised the peace in the community. A need was created for organizing the community into a congregation of family-like subdivisions, from which other males were excluded. This organization would work well for the men to secure access to women on an orderly and a long-term basis and to increase the certainty of biological fatherhood. For the physically weaker women attachment to specific men could mean an optimum tactic for higher security for them and their children, in an epoch where physical power determined the social relations. On this view, the family life was an efficient peace policy despite the fact that women were made commodities in the hands of men.

The invention of language made it possible to replace fights with social codes and mutual agreements for determining which men had a right on which women. If rivalry necessitated the creation of the family as an institution, it could now be possible to secure its unity through a formal blessing. Ceremonies were arranged to signify this event. Literature on ancient wedding ceremonies is numerous. Historians suggest that the first Persian marriage may have occurred during the Zoroastrian era. The invention of language made it possible to replace fights with social codes and mutual agreements for determining which men had a right on which women. If rivalry necessitated the creation of the family as an institution, it could now be possible to secure its unity through a formal blessing. Ceremonies were arranged to signify this event. Literature on ancient wedding ceremonies is numerous. Historians suggest that the first Persian marriage may have occurred during the Zoroastrian era.

The formal marriages transformed the basis of sexual relations. Economic needs rather than purely physical rivalry became the determining factor and the basis for the creation of a family. For the most part it worked well for its purpose for millenniums. Sex became an expression of economic and social, rather than physical, dominance. Indeed, arranged marriage is but an extension and a natural progression of a move from free sexual practices to a more cultivated form of organized sexuality.

The birth of the major religions transformed again the basis of sexuality. Marriage was now politicised and moralized, and culminated with Islam to a moral obligation. Far from being neglected, sexuality became an issue for the public domain in the Middle-Ages onwards. Foucault (1926 -- 1984) argues in The History of Sexuality how the free act of sexuality was gradually transformed into a discourse on sex, i.e. an obsessive talk about sex in Europe (and certainly elsewhere in the world, as the evidence seems to suggest). Sex became indeed so important that even the worth of humanity was closely linked up to a person's sexual habits and orientation. Homosexuals and prostitutes were regarded less worthy and subjected to systematic persecution.

It took about two millenniums before the foundation of marriage was rocked yet again. Sex had been developing increasingly in the direction of formalization and ritualization. The transformations of the twentieth century in the West reversed for the first time this development. The sexual liberalization and the liberation of women liberated not only sexuality (arguably only to a lesser extent), but also human worth from the bondage of sexual oppression and prejudice. Humans were now acknowledged valuable regardless of their sexual orientation. Humanity regained its autonomy and respect. Sex became an expression of freedom, but what about marriage?

With the liberation of man from sexual oppression a contradiction emerged: marriage became the union of two equals, but not two autonomous and free individuals as the parties reciprocally, even though out of love, trade their autonomy and freedom for unity. Indeed, marriage is nothing less than a promise of mutual, but exclusive right to one another. Is this not hypocrisy and contrary to the free man? With the liberation of man from sexual oppression a contradiction emerged: marriage became the union of two equals, but not two autonomous and free individuals as the parties reciprocally, even though out of love, trade their autonomy and freedom for unity. Indeed, marriage is nothing less than a promise of mutual, but exclusive right to one another. Is this not hypocrisy and contrary to the free man?

Contradictions in our moral attitudes are more common than one likes to admit. Take, for example, the widely accepted moral norm: 'it is a duty to save the lives of people hit by famine'. Considering the magnitude of the problem of famine, full compliance to this norm forces the complier to an existence minimum since she will be required to give up her resources to the limit of marginal utility in order to save lives of the needy.

A partial compliance means nothing but to help just a few to ease one's conscience and overlook the deaths of others in order to indulge one's remaining resources on personal pleasure. Yet most people think it is a madness to give up one's resources to the point of existence minimum at the same time as they seem to hold the contradictory view that no unnecessary indulgence is worth the loss of even one single life. Why? Perhaps because the duty to help the needy, despite its inherent contradiction, is the only practical solution to an oversized famine problem. The practicality of the situation has thus concealed the inherent contradiction in our moral attitude

Much in the same way the underlying contradiction of marriage might have been concealed had marriage worked well. However, the unworkability of modern marriages and a high divorce rate, as I pointed out in "Till time do us part", will bring the contradiction up to the open and gradually encourage a change in the way intimate relationships are erected.

A union free of contradiction must be but a union of two autonomous individuals purely based on love and affection where no degree of autonomy is traded for stability -- a union, which will last as long as the mutual love lasts but not one minute longer. A union free of contradiction must be but a union of two autonomous individuals purely based on love and affection where no degree of autonomy is traded for stability -- a union, which will last as long as the mutual love lasts but not one minute longer.

Today some couples in the West, including some Iranians who live abroad, have chosen to experiment freer forms of sexual practices under a controlled environment. A degree of free love is practiced, but only as long as they both agree. Though these experiments are a step on the way towards a complete change and liberalization of modern relationships, they still fail to qualify for their purpose. The same mechanisms of oppression and control are present in these types of experiments too, as couples have to trade mutual rights for sexual relations to external partners.

The question remains how would fully autonomous sexual behaviour look like? The only clue available is the model of homosexual relationship. Homosexuals come together for love and affection and, at least in theory, free from socio-economic power relations. It may just be that heterosexuals increasingly move away from the traditional marriage towards a model of love similar to that of homosexuals.

|