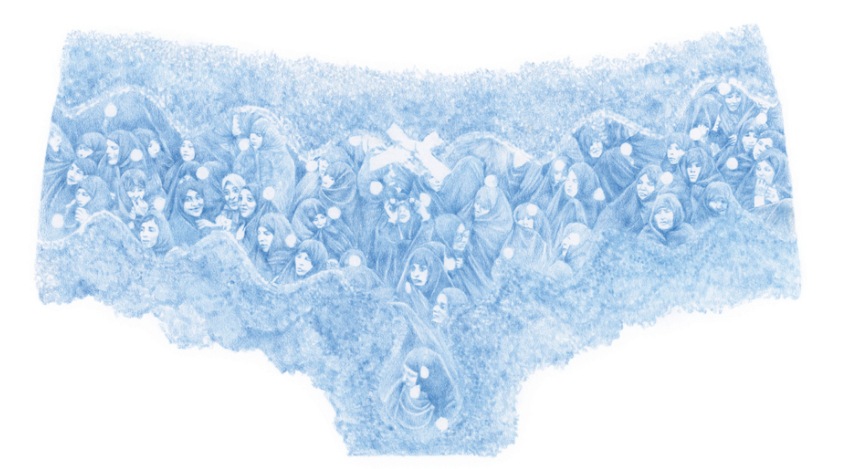

If you do a web search for Azita Moradkhani, you’re likely to first find images of lingerie. The young artist, currently stationed in Utica in upstate New York, inspired quite a stir with her “Victorious Secret” series, a collection of startlingly precise and detailed colored pencil pieces which satisfy the pun-influenced title. The craft and fastidious attention of these pieces of art requires additional glances, however; within the articles of underclothing are various images, practically hidden within the lines at a distance. In a gallery, you might step closer, but on the internet we just zoom in.

Moradkhani was born in Iran, but has been living in the US since 2012. During that time, she’s accumulated an impressive number of accolades and distinctions, and crafted some works that I would opine are quite advanced and investigative for a creator at the initial stages of her career. This thoughtfulness extends to her insights on art as well, with a clarity to her written personality that handily escapes my own ability to self-evaluate.

We caught up on the phone today to quickly touch base on the detailed responses she had sent over to me, and there was some concentration and care towards being properly quoted. She related the balancing act to me: “Some artist’s work, like Shirin Neshat, get into some [marked controversy]. I’m trying not to be specifically in conflict with anything in my work. Some have saw fit to call me a feminist, but I don’t like being put in a position against aspects like a specific gender or religion or skin color.”

I interrupted her with the comment, “Is that in relation to maintaining your agency as an artist?” She agreed that it was, which is sensible to me, especially when contending with the mysterious character to her ornate pieces, including a series of body casts that were made from her own nude form. There is something a little playful about it, an element which disguises the severity in some of these pieces, informing a design where even a nude body or an undergarment is actually laden with additional secrets. I think this may be the trick to appreciating some of the beauty in her work.

Or maybe it’s more pointed than that. The Guardian’s Cynthia Corbett wrote this memorable quote in praise of Moradkhani: “Beauty is her weapon to make political points aesthetically approachable.” What did Azita think of this evaluation?

“Aesthetic pleasure is a way that I get attention to my drawings, at the start. But then, when you get closer to my lingerie drawings, you will see the shadows and the images that are telling stories about people around the world. Some of those challenge even assumptions and ideas that I have in my own life. Describing it as a weapon is where that tension comes from. I have no problem with that statement!”

The Iranian graciously thanks Azita Moradkhani for speaking with us about her work.

The Iranian: What was your first memorable encounter with visual art?

Azita Moradkhani: My father’s oil paintings were my first memorable encounter with visual art. He is an artist and he used to paint at home after a long day working in a glass workshop, supervising workers to cut and design glass for installation in huge commercial buildings. Painting is his passion and he used to have a corner of the living room where he set up his easel to start painting right after dinner.

The Iranian: The first thing I’m drawn to about your work [specifically the lingerie series and the body-cast series] has a lot do with a sense of discovery. The pieces have a kind of hidden life inside them, appearing detailed but still somewhat unassuming from a distance.

Do you create art with this sense of mystery, otherwise? Is that aspect important or deliberate in your work?

Azita Moradkhani: Yes, it is. My series of drawings “Victorious Secrets” were based on the impression I got from walking into a Victoria’s Secret store in the US for the first time. Seeing such a large lingerie store in public surprised me, since in Iran such stores were private, secret spaces. The drawings of intimate lingerie on paper in colored pencil use imagery culled from photojournalism and iconography to explore connected narratives of pain and pleasure.

In the center of a sheet of white paper, viewers see detailed lace of recognizably expensive panties that are ascribed by both very light and heavy pencil markings. Yet when viewers look more closely through the layers of colored pencil, past the details of lace and filigree, disruptive iconography become apparent, narrating inherited histories of nation and belief, engaging us in more complex ways.

The Iranian: I don’t get a particular sense of religious imagery in your work, nor a sense of fantasy, necessarily. Would you describe your focus, at least in part, as a kind of modern realism?

Azita Moradkhani: Inherited religion used to help me access answers about the ambiguity in the world, but its violence and assumptions made me question its relevance in modern and post-modern societies. The majority of religions put pressure on the female body to conform to certain standards, as with the obligation to cover the body or issues surrounding access to contraception and abortion. So I began wondering whether my most trusted, accessible, and safe place could simply be myself.

In the beginning, my body casting project was more about the process than any final piece. [In other words,] through the collaborative process of casting my body, I put myself in a vulnerable situation that had been closed off because of my connection to strong cultural and religious beliefs.

Growing up in Tehran, I was exposed to Persian art and culture as well as Iranian politics, and that double exposure increased my sensitivity to the dynamics of vulnerability and violence that I explore in my work and art making process.

The Iranian: You’ve mentioned before that you moved a lot in the US after immigrating from Iran. Where did you travel during these moves? Did you feel like it provided an important sense of this country, by seeing a lot of it, and do you think that this informed your work? If so, how?

Azita Moradkhani: I moved to the US (Boston) in 2012, and over the first two years I moved five times for various reasons, like improper heating systems, mice, noisy/criminal neighbors, etc. My work from that time is about displacement as an unnatural state we experience when we find ourselves insecure in our own bodies. The ambiguity of the space, violence and peace, and the experience of pleasure and at its simultaneous denial are polar opposites that could be seen as themes in this body of work.

In addition, over the years that I was constantly moving, I started taking snapshots from everyday life here in the US. Gradually, I transformed those moments into my drawings. I tell stories with my work, and those earlier drawings inspired me to incorporate images based on photojournalism and iconography into my later projects.

The Iranian: You immigrated from Iran rather recently and, from what I understand, you still have family there. Has this part of your family been able to get a sense of your art in the past few years? Are they supportive or critical?

Azita Moradkhani: My father is an artist and a spiritual person. My parents always support me in following my passion and give me the confidence to believe in my ability to achieve my goals. Lots of people including my family got to see and know about my work through a television interview. They are mostly happy for what I am doing in my artistic career, and I have been fortunate to have them in my life.

The Iranian: Are there modern Iranian artists you look to for guidance, inspiration or conversation?

Azita Moradkhani: There are many contemporary Iranian artists whose work I admire, such as: Tala Madani, Sia Armajani, Monir Farmanfarmaian.

The Iranian: Do you feel like your work contributes to a conversation with your nation of birth, and where do you see yourself in that conversation?

Azita Moradkhani: Growing up in Tehran, I was exposed to Persian art and culture as well as Iranian politics, and that double exposure increased my sensitivity to the dynamics of vulnerability and violence that I explore in my work and art making process. A sense of delicacy and colorful patterns connect my work aesthetically to Persian art; from childhood I was surrounded by intricate Persian carpets and textile designs. For me, the patterns are traumas that repeat unconsciously regardless of their aesthetic aspects, and the pleasure leads to pain and feeling overwhelmed in my drawings.

The Iranian: Can you tell me a little bit about your current teaching role and how it may have come about?

Azita Moradkhani: It has been my pleasure to teach two classes during my residency at MWPAI (Munson Williams Proctor Arts Institute). While the content of one of my classes, “Fine Arts Seminar,” is more theoretical and discussion-based, my “Studio Drawing” class is more practical, and based on fundamental drawing skills and techniques.

Considering my own passion for teaching, based on my first masters in Art Education, it has been a blessing for me to be able to share what I know with others. Wondering, thinking, and questioning are some of the most fundamental aspects of my artistic process, and teaching has been a great opportunity to share that with students by making it a platform for creative discussions.

The Iranian: Regardless of the attention on your art, do you see yourself continuing to pursue teaching in an ongoing fashion, as you pursue your art?

The campus, the faculty, the students, everyone is so nice, well-educated, and professional—but the teaching takes a lot of time and energy for me. Maybe it’s because I just started teaching, but it’s been a big challenge for me to keep that balance with my [teaching responsibilities]. So I haven’t been in my studio to make art from the time I moved to Utica, which is almost a month ago. I’m trying to figure that out. But as I’m moving forward, I do see that the teaching process is getting smoother, and I can see the patterns.

I really enjoy the challenges, especially the “Fine Arts Seminar” class, which is all about the philosophy and history of art and contemporary art. All the questioning and reading and writing, it really helps me as well, and helps me research the ideas that I have in my own body of work.

I’m going to the Yaddo residency for the Christmas break, and will finish my Utica residency in May 2018. I’m hoping to continue this journey as an artist through different residencies for one more year. It’s been an amazing, interesting experience.