When the prime minister of Lebanon, Saad Hariri, suddenly resigned from office while visiting Saudi Arabia on November 4, the Lebanese people and their leaders struggled to make sense of it. First they were shocked when they watched Hariri’s deeply unsettling eight-minute resignation video, which was broadcast on Saudi satellite network al-Arabia instead of being submitted to the Lebanese president. Hariri then went silent for a week before returning to Lebanon on the eve of Independence day. He has now announced that he may withdraw his resignation after all.

So far, no detailed explanation for this bizarre sequence of events has emerged. But many in Lebanon and beyond agree on the reason behind Hariri’s resignation: Saudi alarm at Iran’s increasingly confident meddling in wider Middle Eastern affairs. Above all, Lebanon is under Saudi pressure because it remains home to one of Iran’s strongest allies, a powerful force that engages in conflicts beyond the Lebanese border: the militant shia and Iranian-allied group Hezbollah.

Hezbollah began life in the 1980s as a resistance movement formed to defy the Israeli occupation of South Lebanon. After Israel withdrew in 2000, Hezbollah, unlike other armed groups fighting in the Lebanese civil war, retained its arsenal of weapons as a deterrent. Since then, the group has formed an official political party and has joined successive Lebanese governments and filled several cabinet posts.

Hezbollah contended for years that its growing arsenal was solely for defence in case of an Israeli attack. But in July 2006, after 34 days of battle between Hezbollah and Israel, a ceasefire was accepted by both warring parties. That Hezbollah was not defeated militarily by Israel was considered a victory for the former and became a cause for celebration across the Arab world. But at the same time, it marked Hezbollah out as a potential threat to regional stability, a status the group retains to this day.

Muscling in

Hezbollah’s political and military power grew throughout the ensuing years, but it was soon put to the test. As reverberations of the Arab Spring hit the streets in Syria, Bashar al-Assad’s government worked with Hezbollah to fend off militant groups trying to topple the regime. Fighting alongside the regime’s forces, Hezbollah came to play a critical role, helping win the strategic battle of al-Qusayr in 2013.

In the years since the Syrian conflict began, Hezbollah’s military power has grown disproportionately to its size; it secured unhindered access to arms supplies and valuable field experience. Politically, however, the group has been under constant pressure from within the Lebanese government to withdraw from Syria, because of concerns it might entangle the country in a war it wants to avoid at all costs.

Lebanon’s official position towards the complex conflict across its border is to stay out of it. The country is too weak, both politically and militarily, to engage in a conflict that was quickly becoming a Saudi-Iranian proxy war. Nonetheless, Hezbollah was not going to sit idle and watch Iran – its closest ally and regional sponsor – fight alone to save the Assad regime, whose assistance guarantees Hezbollah’s own survival.

With boots on the ground in Syria, Hezbollah became something much more than a mere resistance movement against Israel or a political party with a military wing. It possesses power that is typically reserved for states rather than political parties or resistance movements: the power to help regimes rise or fall.

Thin ice

If Hezbollah wants to stay in Lebanon and maintain its power base there, it needs the Lebanese government’s political cover. That means it cannot afford to push its boundaries. Hariri has failed to curb the group’s words and actions against Saudi and its interests, and that would explain why Riyadah invited itself to interfere so boldly and directly in Lebanon. By detaining Hariri and orchestrating his resignation, the Saudis sought to pull the political rug from underneath Hezbollah’s feet.

At minimum, they must have hoped to see an outraged Lebanese public – particularly sunnis – take to the streets and pressure Hezbollah to rein in its transnational activities for fear of reprisal. The intended message is that the Saudis can restrain Hezbollah, even at the expense of destabilising Lebanon.

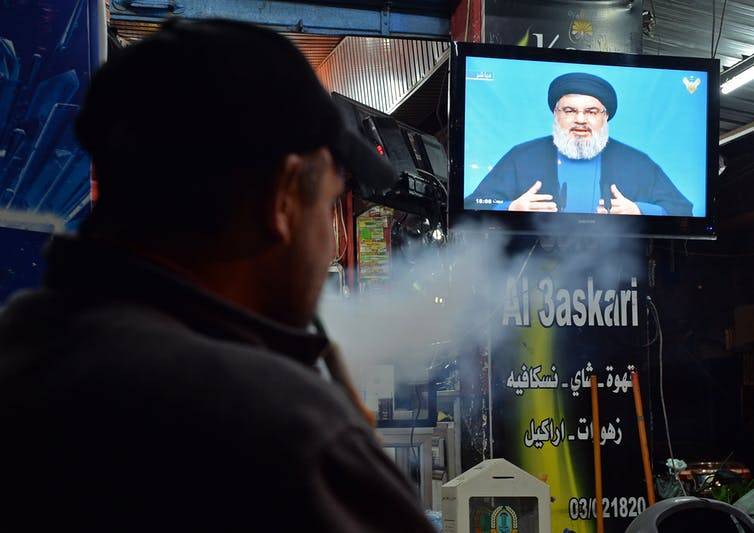

Hariri insists that his resignation was self-motivated, meant as an alarm bell to call his government back to the principle of disassociation. But the president, Michel Aoun, is not convinced – and he refused to accept the prime minister’s resignation before speaking to Hariri. Aoun, who is a political ally of Hezbollah, considered Saudi detention of Hariri an act of aggression against his country. For his part, Hezbollah’s general secretary, Hasan Nasrallah, called for patience and for measures to deescalate the situation.

This article was originally published on The Conversation.