Our Persian boy Our Persian boy

Conversations with Farhad

Diba

By Fariba Amini

January 15, 2004

The Iranian

Do not go where the path may lead, go instead where there

is no path and leave a trail.

-- Ralph Waldo Emerson

I got into my seat at the conference in Chicago. The first panel

was about to finish and I was looking around in search of some

friendly faces. Sitting next to me was someone that I knew and

I began to talk to him about the conference (Thwarting Democracy

in Iran and Guatemala).

As I turned my head I noticed that, sitting

just behind us, was an older gentleman, tall and gaunt. He handed

some photos to my neighbor. They were photos from the coup d'etat

of 1953, which I had never seen before. He introduced

himself as Farhad Diba. Oh, then I realized that I knew him through

an email he had sent to me regarding articles about Dr. Mossadegh.

I shook hands with him and introduced myself. He was very charming,

had a sort of noble look about him and in his low but kind voice

he explained the photos to us. Immediately I knew that I wanted

to talk to him more about his uncle and his teenage years, when

he had disobeyed his parents and taken off on his own to witness

a historical event in his country; the final acts in the staging

and the planning of the CIA coup of 1953 against his uncle, Dr.

Mohammad Mossadegh.

I had struck gold, as I knew talking to someone

who witnessed history himself and was part of it, was really an

important occasion for me. I have become intrigued by what happened

in those days and the reasons behind it. My interest also lies

in the fact that I ask myself many times over, why are some monarchists

and the religious fundamentalists still so afraid and wary of this

man, even fifty years after the fall of his government and almost

40 years after his death.

Farhad Diba was only 16 when he

encountered tanks, a rioting populace and street fighting in

the capital city, in those eventful days

of August 1953. I put the following questions to him in the hope

of discovering more about the person and the imprint of perhaps

the most famous politician in 20th-century Iran.

TEENAGE ENCOUNTERS WITH A COUP D'ÉTAT

I was at boarding school in England and would sometimes go to Tehran

for the holidays, especially in the summer. So it happened that,

during the summer of 1953, I was staying in Tehran, at our house

in Shemiran. My father's office was an old building, which had

belonged to my grandmother, in the compound of Najmieh Hospital.

Dr.Mossadegh's mother, Princess Malektadj Firouz, Najm-e Saltaneh

(my grand-mother) had established it as a charity hospital.

The office and hospital were on Hafez Avenue, facing the Park Hotel

owned by my father.

During my holidays, on some days, I would accompany

my father to the office, early in the morning and return with him

at 2pm. This is how I found myself in town on 19 August 1953 (28

Mordad). The morning had started quite calmly and there was no

hint of what was to follow. When I heard some rumours of a demonstration

not far from where I was, I ventured out into the streets, armed

with my miniature Minox camera, a recent present from my father.

I

went south towards Hassan Abad Square and, there, I came face-to-face

with a group of demonstrators, heading north up Hafez Avenue.

I tagged along, thinking I would slip back into the Park Hotel

but,

once we reached it, they had closed the very heavy and large

green wooden door. There was a lot of noise and chanting in the

street

and no one asnwered my frantic knocking on the door.

Curiosity overcame fear and I continued following the marchers,

eventually arriving at the intersection of Kakh Avenue. There,

the crowd had become huge. Some tanks were positioned on Kakh Avenue.

Although I was not far from Dr. Mossadegh's house on Kakh (which

also served as the prime ministry), I decided to turn northwards,

away from the crowd, and went to my sister's house on Kakh Circle.

By this time it was around 2pm and the demonstrations had turned

into riots. We telephoned my parents, who sent a driver to collect

me and take me to our house in Shemiran. On the way, all along

the Shemiran Road, there were groups who had created roadblocks.

They obliged every car to take out a currency note, with the Shah's

picture on it, and display it on the windscreen.

The next day, two lorry loads of soldiers arrived at our house

in Shemiran and thoroughly searched it, saying that Dr.Mossadegh

might be hiding there. Other soldiers were despatched to a summer

garden restaurant owned by my father - the Park-e-Now (New Park)

- and completely ransacked the place. I have to add that this restaurant

was extremely fashionable at the time, and presented competition

to the Darband Hotel restaurant, owned by the Shah (Pahlavi Foundation).

When they had finished searching our house, one group of soldiers

was posted at the gate and we were virtually under house arrest.

Later, my sister and I were able to return to England to boarding

school.

THE PERSON OF DR.MOSSADEGH THE PERSON OF DR.MOSSADEGH

My uncle was very good with children and we all had enormous love

and respect for him. Before, during, and after his premiership,

he would unfailingly send a hand-written Norooz note of good wishes

and (as I was at school at that time of the year) he would commission

my father to give me some money as "Eidi", the next time

that my father was in England. Of course, after finishing my education

and returning to Iran, we would make a special Norooz visit to

him, at Ahmadabad.

It was at that simple village house that I came to appreciate

him the most. Perhaps because I was already in my twenties and

also

because on our Friday visits we were only a small family group.

This group, often composed of my father and some or all of Dr.Mossadegh's

children (Dr.Gholam Hossein, Ahmad, Massoumeh Matin-Daftari), would

engage him on some political conversation and I would be glued

to their discussions.

On a personal note, whenever I had a falling out with my father

(and there were many!), I would take my problem to my uncle and

he would iron it out with my father, in a very gentle and logical

manner. Being the younger brother, my father was obliged to follow

the decision!

CHURCHILL AND DR.MOSSADEGH NEVER MET, BUT . . .

I was at a boarding school called Harrow, which has a long list

of luminaries amongst its old boys. The school was divided into

some dozen Houses, for accommodations, and the rooms were triple-,

double or single-bed, depending on seniority. At my time, the beds

were in a wooden cupboard and were folded down at night, to be

replaced inside the cupboard during the day. Inside these cupboards,

past residents would carve their names. Mine had Byron in it.

The

whole system was based on rules and privileges. When we became

monitors (school prefects or guardians of the rules), we had some

very special privileges. Once a year, we had a Churchill song day,

when Winston Churchill (an old boy who had been sacked for failing

Latin!) would come into the auditorium and we would all sing songs.

Afterwards, the monitors would be invited to the Head Master's

study, to take sherry with Churchill. I was introduced to him as "Our

Persian Boy" and, in his usual gruff voice: he said something

like "jolly good, carry on". I have no idea if he knew

my connection to Dr. Mossadegh. By autumn 1953, he had put the

whole issue behind him and, as Stephen Kinzer (author of All

the Shah's Men) has said, Churchill's biographer

states that there is not one single mention of 28 Mordad in

all his memoirs and letters.

My years at Harrow coincided with the oil dispute between Great

Britain and Iran. As a Persian boy, I was well bullied for it!

Other Middle Easterners at Harrow in the same period, were King

Faisal of Iraq and King Hussein of Jordan.

KERMIT ROOSEVELT - THE BUSINESSMAN

Our paths crossed well before my interest in sifting through the

facts of the 1953 coup d'état. Roosevelt was an advisor

to the National Cash Register Company (NCR) of Dayton, Ohio. I

was a member of Abolhassan Diba & Co., a multi-faceted company,

established by my father in Tehran in 1922. A section of our work

was the representation of NCR in Iran, for which I had to go very

often to Beirut, where NCR had its regional HQ. Roosevelt had an

apartment there, at one time, which he shared with Miles Copeland.

My brother-in-law, Frederick Benedix III, lived in the same building.

Some time later, In Tehran, I was invited to a small dinner at

the Palace of the Shah. Roosevelt was there. The Shah asked me

what I was doing and I, very proudly, told him about how well NCR

was progressing in Iran. When I reported that to my father the

next day, he said "You are a fool". Sure enough, within

the year, NCR (which my father had introduced into Iran and, over

25 years, it had grown into a large business) was taken from us

and given over to the Pahlavi Foundation. I learned that Roosevelt

had been given a 3% share - presumably for his intervention.

About ten years later, in 1978, I was in Washington to research

and interview for my book on Dr. Mossadegh. I met up with Roosevelt

and, without telling him that I was writing a book, I asked him

to tell me about his days in Iran during 1953. We had a few lunches

together and dinner at his house, where he and his wife Polly were

generous hosts. Kim liked his vodka and he also liked to brag about

his exploits and his involvement in the coup d'état. Depending

on the intake of vodka, the story would be recounted in various

versions.

KHADIJEH MOSSADEGH

She was Dr. Mossadegh's youngest daughter, out of three daughters

and two sons. She was a teenager when, in 1941, her father was

arrested and sent to prison in Birjand. On the way, he tried

to commit suicide because he knew that Reza Shah was going

to have

him killed. This was known to others and especially to his young

daughter, who worshipped her father. She was staying in our summer

house in Shemiran when, waking from a nightmare in the early

hours of the morning, she ran with her nightgown to the garden

gate and

shouted to be let out to see her father.

My parents brought her

back to the house to calm her down and I, then only a 4-year

old, still vividly remember that I was placed on her lap

and she was

talking to me. Anyway, her health became worse and she was

operated on, but the operation went wrong and she went into a vegetative

state. They sent her to a clinic in Switzerland, where she

remained

for over 50 years. Her hospital expenses were paid out of a

trust, which her father had set up for her in Tehran. At the revolution,

these assets were seized and, for the rest of her life, her

cousin

Majid Bayat (Dr. Mossadegh's grand-son) cared for her. She

died a year ago in Switzerland.

ARDESHIR ZAHEDI

I have enjoyed friendly relations with Ardeshir and, through

his mother, we are distantly related. He has always been

very kind

to me and I have enjoyed his hospitality wherever he was

as ambassador, as well as at his house in Saheb-Gharanieh.

We

never discussed

my uncle and, until I started my research, I was not aware

of his close involvement. Since the revolution, I have only

seen

him on

a couple of occasions, at a family funeral.

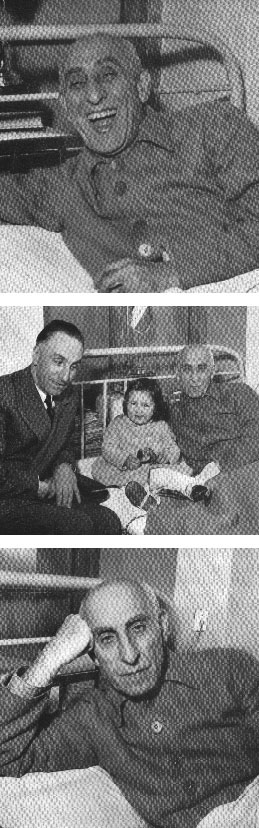

DEATH OF DR.MOSSADEGH

I was very close to my uncle during his last days. He

was allowed to come to Tehran and was at the Najmieh Hospital.

Since my office formed a part of the same complex, I was

at his bedside many times during the day.

One day, when he felt a little better, he expressed the

desire to see how Tehran had changed. Ahmad Mossadegh

had a blue

Volkswagen and he seated his father in the back, so that

he would not

be noticed. I sat in front with Ahmad Mossadegh driving

and the

three of us

took a short drive around the area of the nearby streets.

At one point, someone recognized Dr. Mossadegh and, with

an incredulous

expression, pointed him out to other passers-by on the

street. We then made haste to return, as he did not want

to contravene

the terms of his right to stay in the capital.

Some days later, I had only left him a few hours earlier

and was in my office when the news came of his death.

Of course,

I rushed

over to the hospital and the family quickly gathered.

Dr. Gholam Hossein Mossadegh, his son, contacted Mr.

Amir Abbas

Hoveida, to

see if they would allow for the burial to take place

according to

Dr. Mossadegh's wishes, alongside of those who died

during the 30th

Tir riots.

The reply came that the Shah would not permit

it and would only allow burial at Ahmadabad, Dr.

Mossadegh's country

house, about 140 kilometers from Tehran, and that

there was to be no funeral procession. His corpse was placed

in a white

ambulance

and we began to follow it. However, the driver must

have been

a Savak agent and tipped off to prevent any kind

of cortege building up. So he took off at a fast pace and tried

to shake off the

line

of cars that were following.

Anyway, we met up at Ahmadabad and dug a grave for my uncle in

the ground floor room of

his house,

which had previously served as a dining room. It

was a very simple burial and an extremely touching scene.

Personally,

I felt that

this was more appropriate for him, because he had

never been

one for pomp and ceremony. [Present were Ayatollah

Taleghani and Zanjani who did the Islamic burial.]

I never heard Dr. Mossadegh clearly putting the blame

of his downfall on anyone, except for the British.

It could

be argued

that, by

the same token, he was including the people who

helped the British, covertly or overtly. I think that he

considered his undertaking,

namely the nationalization of the oil in Iran,

as a dangerous task and that he accepted his downfall

as

something to

have

been expected.

He envisaged that he would be assassinated and

was well aware of his enemies inside the country.

Dr. MOSSADEGH AND THE NEW GENERATION

The very fact that there is so much interest in his legacy, adverse

or sympathetic, is proof enough of the man's lasting mark on

his country - Iran. The generation that did not experience the

Mossadegh era in Iran is now marking that period as a time of

democracy and national self-determination. It is seen as a moment

when Iran held its head high and viewed itself as a proud nation.

Generally, there is a thirst for secular democracy, clean, honest

and truly participatory. Dr. Mossadegh is now viewed as the embodiment

of that desire.Farhad Diba now lives in Spain. He has collected

a vast library of books, newspapers and periodicals, photographs

and archival material on Iran, in European languages.

This library,

covering every aspect of Iranology, is the largest of its kind

in the world and is now in the process of being catalogued by

him. He has written two books: "Dr. Mohammad Mossadegh:

A Political Biography" and "A Persian Bibliography".

He is currently revising the book on Dr. Mossadegh for a new

paperback edition.

I asked Farhad if he had any letters addressed

to him directly by Dr. Mossadegh. His reply was: "all my

letters, photographs, tape recordings of my uncle (which I had

in Iran) were stolen from my house, when the akhunds ransacked

it and grabbed it. Especially my father had a superb collection

of letters from his brother, but they all went as well."

Note

Many readers have asked how it is that Dr. Mossadegh's brother

is a Diba and if he is related to Farah Diba? Dr. Mossadegh's mother,

Najmieh Saltnaeh was married three times (unusual for those times).

One of her husbands was

a Diba. Farhad Diba is therefore related to Farah Diba Pahlavi.

* Send

this page to your friends

|