Inside a different city Inside a different city

Five weeks in a refugee camp in Lebanon: Part

2

By Sina

Rahmani

December 15, 2003

The Iranian

First Impressions of the Ajnabi

Arabic is a very hard language to translate. Often, the nuances

of the language are lost in the clumsy translation to English.

Case in point: intifadah. Non-Arabic speakers understand the term

to directly apply to the social movement against Israel's

occupation, or uprising. But the word itself has nothing to do

with Palestinians, or even a social movement; when

translated directly the word means "to shake off, to be rid

of".

Although Palestinians themselves decided

to name the social movement to end the occupation of their land

as an "intifadah," the semantics of the word are endemic

of the misunderstanding that exists between the Muslim/Arab world

and the West.

During my first few days here in Bourj-el-Barajneh,

I kept hearing this word: "ajnabi". I finally asked

one of my translators and he said it meant "foreigner". I

laughed nervously, but it weighed on me for a couple of days. So

much so, I approached

the only other "ajnabi" in the camp, an Australian

physiotherapist who has been training women in camps.

She laughed it off saying that in the camps, ajnabis are

considered guests, to be welcomed and thanked (although this has

exceptions, sad).

I was warned by the camp residents that the first

few days in the camp would be the hardest. Indeed they were.

The conditions in the camps are horrible. The camp

entrance is to be found off An Nan Street in the south Beirut suburb

of Bourj-el-Barajneh.

The first thing one notices is not the smiling portrait of Yasser

Arafat that seems to make the man out to be larger than his five-feet

four inches, but the smell. The smell of garbage is not only terrible,

but is also serves as the first test of wits for the idealistic

ajnabi who steps foot into the camp; for although the smell of

garbage is so strong that it burns the sinuses, there are only

a few scraps of garbage that can be seen. The smell seems to hang

over the specific square kilometre that the camp occupies, reminiscent

of the Don Delillo's White Noise.

Further confusing the poor ajnabi are the camps

intricate pathways. Although use of the term pathways is misleading

because there are

no paths in the camp and one must find his own way. Putting aside

the emotional chaos one feels realizing how many people actually

live in these camps, part of the problems for outsiders in the

sheer lack of mobility. This exists on both the psychological and

physical levels.

Indeed there is no physical space in the camps;

the paths at some points are about 35 cm wide. The most spacious

path that I have been able to find--what foreigners last year decided

to name "Champs Elysees"--is about a meter wide. This

creates some sort of demented Indiana Jones like gauntlet where

the poor ajnabi must navigate through the sewage, mangled pavement,

tight turns, leaking

water pipes, and the windows opening in the face (I had the personal

privilege of experiencing the latter, but the locals had

a good hoot over that one and told me it happens to everyone).

The greatest part of the entire charade is that there

are no signs or arrows or any distinguishing "you are here" spots.

All one has to go by is the landmarks: a broken

pipe here, a poster from Fatah or Hamas there. So, unless one's

Arabic is strong enough to converse with the locals

well enough to understand the complicated directions, the visitor

is at the whim of the coordinators

or the people they send to pick you up.

But the real shock is when one enters a house in

the camp. The entrance to the houses give a hint as to what is

to come: ancient

steel doors opened with ancient keys. One enters into the damp,

smelly house and is confronted with peeling paint, decrepit stairs,

exposed and fraying electrical wire with seem to mock you when

the power goes out daily. The tap water is not clean enough to

drink or even wash fruit in so the refugees must purchase water.

There is no proper, centralized system for water; only a haphazard

McGuiver approach that it is a testament to the resiliency and

the wit of these refugees.

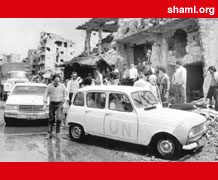

Worst of all, are the reminders of the Amal war.

Amal was the name of Shia Muslim militia that waged a war (with

the support of Syria)

against the Palestinian fighters of the PLO, who were based out

the refugee camps of Beirut, one of them being Bourj. The war became

known as the "war of the camps". Amal laid siege

to the camps for over a month; over six hundred civilians were killed and the camps still show

the damage. There are the shelled out buildings that seem to be

stubbornly refusing to collapse, to the more personal images that

really bring the war into the bedroom. The latter is quite literally

attested to by the door to my room: there is a bullet hole in it.

I asked my host and he said that the door was a door

taken from another house that had been flattened in an effort to

save money.

The bullet, came from an Israeli soldier during the invasion of

1982. When I asked whether or not some one had died as a result

of the bullet, he said probably not because the hole was only a

foot above the floor. Probably not, unless he had been

sleeping on the floor like I am now.

On a happier and more lighthearted

note, I think the people are starting

to take a shine to me. In Arab culture, fathers or other revered

men receive the title "Abu" in front of their name,

followed by the name of their first born son. For those members

of the community who are respected but don't have any sons, the

community creates a nickname related to their character or after

some other

revered figure. I have been named Abu Lowshe ("Low" rhyming

with now; and "she" rhyming with the first sound of "feather");

Lowshe being the name of the region of where the Mediterranean,

since I am Iranian, they thought that should apply. (I thought

about asking what the logic was in the name but I decided against

it; must be an Arab thing).

They challenge me to computer games

and I have to drag myself away from their pleas. When the kids

scream "Abu Lowshe, Abu Lowshe!" I find myself wanting

to both laugh and cry because, in spite of all the hatred being

spewed towards Palestinians by so many people of the world, both

past and present, they can still accept this ajnabi as one of their

own >>> Part

3

* Send

this page to your friends

|