Inside a different city Inside a different city

Five weeks in a refugee camp in Lebanon: Part

4

By Sina

Rahmani

December 17, 2003

The Iranian

Lebanese Water Torture

It is quite possibly the worst sound one can hear: a catfight.

Surprising that such a small little creature is capable of making

the worst sounds. And to sweeten the deal, the worst catfights

happen between 2 and 3 a.m. Could be that the roughest

cats come out at that time, the council of cats must have decided

that that time period would be best because people will probably

entering deep sleep and it is next to impossible to fall back

asleep after being woken up.

The screeching of the wild cats (there are lots

around Lebanon, especially the camps; the guidebook also forget

to mention that

one) is but one of the plethora of sounds that fill the air during

the nights in the camp. There are sounds of people strolling by,

usually this ends at around 1 a.m. Then the workers coming to pick

up the garbage roll by in their squeaking carts, trying their best

to make the tight turns required for navigating the camp.

Then

the airplanes make their circles around the camp, ensuring that

everyone gets a chance to hear their engines. Then there are the

arbitrary sounds of scooters and motorcycles--although at night

these are rare. Then there around the mosque calls--one at around

1:30 a.m. and the other, this one is my favourite, starts at around

4 a.m. Not living anywhere near a mosque at any point in my life,

this last one was probably the hardest

to get used to. And how can anyone forget to mention the arbitrary

neighbour, who spends his days cursing God and his "damn

planet."

All of these sounds usually come and go--eager to

go and annoy other, more stubborn ears. But there is one sound

that one, quite

literally, can't escape: the dripping of water. It's is so constant,

one could actually set his watch to it. Maybe it's the fact

that the water seems to be outside the window I sleep near, or

maybe it's the camps quirky sense of humour, but I have not

been able to outrun the dripping. I have these huge thick pillows

and I wrap my head around them--to no avail. The water continues

to pour. This could be a lone drip-drop combination, the drip-drip-drip-plop

combo, or the dreaded emptying of the water tanks.

Some context:

because the camp wasn't supplied with underground water pipes,

a complex distribution system has been setup and refined over

the years. But it was designed in such a way that from time to

time,

the tanks of sewage need to be emptied into the sewers. This

can happen at arbitrary points during day,

and, as I have unfortunately learned, at night. Although I have

only been here a week, I can tell which sound relates to what

action or even, dare I venture, which house the sound is emanating

from. The

entire process is mind-boggling. Anybody who knows anything and

the Middle East and her wars that behind all the rhetoric about

the cause of the wars, water has always played a central role.

For example, the Camp David II summit where Yasser Arafat and

Ehud Barak failed to resolve the conflict, one of Israel's most

vehemently

pursued goals was control of all water resources.

According to

the Israeli Coalition Against House Demolitions, for every litre

of water that is allotted to a Palestinian

household in the West Bank, four are allocated to Israeli settlers.

It is clear why Israel wants control: he who controls the

taps controls the population to a large extent. If Israel can control

how much water is given to Palestine, Israel can control how fast

(or how slow) Palestine's population can grow. The water debate

seems to be symbolic of the entire Palestinian nationalist struggle:

Palestinians will control their own land, including any foray that

mother nature makes into it.

For example, I was sitting on the

roof/balcony of my house here, and I listened to a boy of maybe

ten whistle for about of half an hour. I finally looked away from

my reading to see what the hell this kid was doing, and I realized

that he had been controlling the flight of a flock of pigeons.

He would whistle and in unison they would turn; he would whack

a stick against a wooden plank and they would fall. I watched this

dance for more than an hour, and it was beautiful. The boy seemed

to be telling the birds: "You can't use your wings until we

have ours."

P.S. I found out why kids are calling me Abu Lowche.

Turns out that one kid

told the rest of them that Lowche means "tall, blonde, European".

Ha. Good to

see that even in Lebanon people who don't know me feel comfortable

enough to

make fun of me.

P.P.S. If you are a vegetarian, don't ever go to

Lebanon. In general, avoid the

Middle East. Felafel is getting tiring. Let me relate to you a

conversation

I had in a restaurant.

"Do you have anything without meat?"

"Why?"

"Because I am vegetarian."

"Oh, ok. Do you eat chicken?"

"No"

"How about lamb?"

"No"

"Hold on." The waiter saunters off to the back of the restaurant.

A

couple of seconds of silence is followed by "What?... HAHAHAHAHAHAH." The

waiter comes back and says, "No problem, we have turkey and

salami."

"Don't Complain About Falafel. We ate Cats"

As the

political power of Palestinians grew in Lebanon, the refugee camps

became

political hotspots. Before the political factions arrived and

took them over, each camp had a boisterous popular committee

that would discuss issues, listen to the concerns of the people,

and issue decisions.

The popular committees were active; they

were comprised of the first generation Palestinians who could

remember the Palestine that

they were forced out of. Their work took on an urgency to reclaim

a lost homeland, which, at the time (late 1960s-1982) seemed

within grasp. A solution was always around the corner; a peace

treaty only a political summit away. But it

never came, and the popular committees became yet another victim

of sectarian infighting that plagues Palestinian politics.

The activists who were serious about affecting change were replaced

with bureaucrats and politicians--typical of most politics in

the Middle East. One such activists was Khalil Mahmood. He was

twelve when he left Palestine, and he became a well-respected

member of the camp. The house

that I currently occupy, belonged to him, and now belongs to

Samer Mahmood, his son.

Samer and I are good for each other. We are both computer nerds,

and we enjoy mocking everything we see on TV. Samer works in

post-production and loves to point out which videos of Arab superstars

he helped edit. Luckily, for me anyways, Samer has not been

going to work for the past week because of computer issues at

his company. He keeps me company during the days because since

most of the youth are at school, I don't have much to do. He

tells me funny stories of documentaries he has edited and his

family. His English is moderately good, but he has a tendency

to mumble so I often have to ask him to repeat himself.

Samer is extremely shy. He essentially

doesn't leave the camp other than for work. He doesn't have anyone

else in the house (his parents have both passed away in the past

two years), so he always eats out or at his brother's house.

He doesn't have many friends in the camp, although he has

been here for his entire life. His life consists of work and

his room, where he enjoys computer games, digital art, and

surfing the internet. I asked his sister about this. "It

was the war. He suffered very

much. He was only three during the Israeli invasion and he was

seven during 'camp wars'. He starved during the 'camp wars'.

I remember he would complain and complain about wanting to eat

chicken and potatoes and juice. We would laugh and ask him where

we could find chicken." Samer's house during the war of the camps was the only

surviving house

among a block that housed four families. The houses on either

side of his were destroyed and the families took shelter in Samer's

house. The room I am writing in once had 36 people living

in it. Palestinian writer Fawaz Turki described how growing up

in the refugee camps in Lebanon he would hang out at the market

for hours to pick up

whatever scraps would fallout of the vendors' carts. He recollects

how Lebanese people would often throw food onto the streets to

watch the starving refugees fight over it like pigeons.

The starvation

was widespread in Bourj. It got so bad that people began eating

the only food that could be found--the meat of the numerous stray

cats that can

be found in the camps. Apparently, Samer refused to eat and he

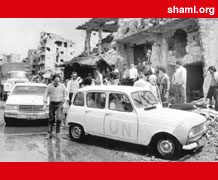

became very thin and weak.The physical scars of the war in Lebanon

are easy to find. Bombed out buildings, abandoned squares, rotting

metal is the only thing in excess in Beirut. These can

be, when there is a will to, easily rectified. But the more pervasive

scars are invisible and manifest themselves in odd

ways.

One of these oddities is Samer's obsessions with Al Khalil

Snack Shop. Al Khalil is famous for its chicken. The bags

from the store are everywhere in the house and he eats there

at least once a day. He eats there so much that relatives laugh

and say that without Samer, the store would close down. He looks

at the menu with an excitement of a

child. He smiles as he rips the skin from the chicken breasts,

and has, to no avail, attempted to bring me back to the carnivore

flock so I can eat with him. He tells me how good the chicken

is, and I tell him that his fries are good enough for me.

During conversations, he is serious and candid with his opinions.

His opinions come across with a surprising seriousness that contrast

his soft spoken nature. He likes to tap your hand when he speaks

to you, and his eyes never leave yours. He speaks of those Palestinians

who have forgotten about the refugees and the struggle for a

homeland. The

Palestinians who sip cappuccinos in the cafes of Los Angeles

who speak of Palestine who have forgotten about the refugees.

And he can't stand it when people complain--as I do, especially

about falafel, my dreaded enemy. "Don't complain about falafel.

We ate cats," he tells me with a smirk >>> Part

5

* Send

this page to your friends

|