Inside a different city Inside a different city

Five weeks in a refugee camp in Lebanon: Part

6

By Sina

Rahmani

December 22, 2003

The Iranian

On Mountains and Guns

The Koura Plateau is a mountain range that is home to predominantly

Christian Lebanese. The region is known for its beautiful lakes

and the source of some of the finest olive oil in the world.

I stayed with a friend from university in a small

village, which was mostly Greek Orthodox--a minority in the predominately

Maronite

Christian community

in Lebanon. His house was situated on a smaller mountain, thus

causing his housed to be dwarfed by beautiful, luscious mountains.

The view from his porch was breathtaking. At night, one could make

out the roads by the cars driving on them; the roads being reminiscent

of a knife pulled through raw cake batter.

I spent most of the days driving around with my

friend and meeting his friends. They took a shining to my English

and did their best

to communicate with me. They would implore me to tell them some

English jokes, which were haphazardly translated. They would invite

me into their cars and would take me on driving tours of the area

(I think I did the same tour at least a dozen times

by that many different drivers). They asked me about my politics,

my background, and whether

or not I liked Lebanon. Every night we would hang out at the local

cafe/restaurant and smoke nargileh. We would sit and talk for hours;

laughing and making fun of eachother (and me).

The town I was staying in was a stronghold for the

Syrian Socialist Nationalist Party. The SSNP believes in what they

refer to as a "natural

Syria". The logic being that is the fact the Middle

East today is only the way it is because the European powers carved

up the territory of the Ottoman Empire and divvied up the bounty.

The SSNP believes that these territories (Iraq, Palestine, Syria,

Lebanon,

Jordan) should come under the banner of one Syrian state.

When

I pointed out the flag, they were amazed that I had heard of it

let alone recognize the logo. Many of the men in the town had fought in the

Civil War and told me some stories.

"William's dad,

he has a bullet stuck in his ass," my friend tells

me, with the group of fifteen people my age hooting and hollering

to William's dad to show us the bullet. "It's on his thigh." William

defensively points out.

Turns out William's dad, a card-carrying SSNP member,

fought in the Civil

War against Christian Maronite forces, who were unabashedly anti-Syrian.

But while these groups of pro-Syrian forces were fighting alongside

Palestinians, pro-Syrian Shia Muslim militia Amal was waging war

against Palestinians in the camps. Thus continues the complex web

of politics that surrounds this insane war. (Actually, the

more I try to understand this war, the more I realize that they

chose the wrong symbol for Lebanon. Instead of a cedar tree, an

onion would have been more suitable--both in composition and effect.)

The leftovers of the war don't just lie in the poor

man's rear, but in the guns that most people have in their homes.

From pump-action,

to double-barreled shotguns, to Walter PP7s to Kalashnikov machine

guns--the instruments of death and destruction abound even in the

most remote villages. On the surface, people use them to hunt and

ward off possible trouble makers who apparently hang around the

mountains waiting to pounce on unwitting travelers.

More realistically, they are a manifestation of the

distrust left by the Civil War.

Paranoia and conspiracy are rampant in this country -- what Robert

Fisk referred to as "The Plot". The Syrians

killed so and so. The Israelis planted this bomb. The Palestinians wanted West Beirut.

Hezbollah wants to have an Islamic revolution. Henry Kissinger

planned the entire civil war.

The lack of a real democracy in Lebanon

(Syria is the real decision maker in this state) fuels this.

The constant worries about the moukhabbarat (secret police)

make people

uncomfortably laugh or visibly worry at the very mention of its

name. Too many people, guns, the very same guns that destroyed the country, are the only piece of protection

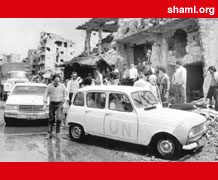

they have from the fractured country they love so much. Among the Concrete Rocks

The beauty of the Koura juxtaposes itself oddly with this place.

Being back in the camps I have been readjusting to life here

and it has been an odd forty-eight hours. Although the luxuries

and the wonders of mountain life I will miss, the smile that

is brought to my face by the wonderful souls here in the camp

have more than made up for it. (When I got home, I asked Samer

if he missed me: "I

wouldn't know, I slept through most of the week you were gone.")

We stood on the roof and drank some arak I brought back. Arak

is the national drink of Lebanon; not surprisingly,

in needs to be watered down and drank "on the rocks". One

would be insane to drink it straight.

As I looked out over the

camp yet again,

I realized what the really depressing aspect of camp life:

the hardness. The view from here consists of concrete homes

that

sit beside each other in some odd formation. The outlook has

a sobering effect: how long could these concrete homes sit?

Could these homes sit for another 50 years? How long would

these Palestinian

refugees be here? How long could they survive in these conditions?

In the homes in the Koura, even the most dilapidated ones

destroyed by the war, one could feel the tenderness

of the children that ran through the corridors. The floorboards

creaked with a

song of

the millions of steps they have felt. There is a sense of

collective history that homes inherently represent. Houses,

more correctly,

homes, are meant to the forum through which we make our history,

through which we build our destiny.

The camps, on the other hand, represent the opposite, the

negation of history. They stand as a testament to the stolen

history

that these refugees have to cope with. The houses here

mock history.

They are a raised finger to all notions of progress and

development. The camps, and states of poverty in general, are

the fundamental

denial of a basic destiny that every human being has the

right to.

It is the attempt to reconcile myself with these

truths, I

tell myself that eventually these refugees will leave

and this place

will be destroyed. Hopeful as this may sound, but, these

may be the final years that these Palestinian refugees

will be

here. This is not to say that wherever they may be implanted--the

various

plans in the working have included Canada, the United

States, various European countries, and some Arab states in

the Persian Gulf--will be

tantamount to social justice. (Incidentally, I read Rosie

Dimanno's latest

rant, this one of the Right of Return. Scorned

be the man who denied us the ability to tar and feather).

But I always fall back to the souls who were

born and grew

up and died in this place. Where is the justice for

those stolen lives? Does the Road Map plan on resurrecting

the dead and

attempt

to grant them citizenship in various countries in hopes that they

forgive us for allowing this to happen to them.

I guess

I will

never be

able to reconcile myself with that; much in the same

that there really is no way to apologize to those

indigenous people we

annihilated in our conquest of the area we call Canada.

There really is no

way to take the truth straight. Therein lies the

true harshness

of this horrible place filled with wonderful people >>> Part

7

* Send

this page to your friends

|