به زبان فارسی

PICTORY

LATEST MUSIC

SEARCH

Kabul Days (11)

by Hossein Shahidi

27-Apr-2012

PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

All Quiet at the Duty Free

Friday 21 March 2003

This has been my quietest Friday since I arrived in Kabul. Also, the first day I have heard music being played in the neighbourhood, to mark the arrival of Nowrouz.

We spent much of the morning watching the news – the missile attacks on Baghdad, the advance of American and British troops into Iraq, the capture of Faw, which was seized by Iranian forces about twenty years ago and taken back by the Iraqis at the cost of thousands of lives, the surrender of some Iraqis, etc. etc. Overnight and during the day, aircraft continued to fly overhead, presumably American planes involved in the fighting down south. Kabul was quiet, though.

Solmaz [Dabiri, an Iranian colleague from the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR),] came over for lunch, and in the afternoon we spent a few hours sitting on the tiled porch in the garden. The weather was just fine, and it was lovely to listen to sparrows and Moussa-koo-Taqi, or moossichech, as they are called in Afghanistan. About two dozen sparrows descended into our garden and picked up whatever they could find in the grass. The sun had warmed the earth and columns of ants were walking up and down everywhere. Watching them, I was taken away from all the tanks and planes and rockets which were still being reported on TV inside.

By around 4pm, our security officer rang to say we could go back to the office tomorrow. So the UN plane might also fly, and I can leave for London, unless there’s a sudden turn of events down in the Persian Gulf. I hope not.

Saturday, 22 March 2003 (Kabul-Dubai)

It was a horrible morning. The US and Britain had fired 1,000 missiles into Baghdad, at a cost of more than the budget the Afghan government has asked for, and not received. All our Nowrouz greetings had to be prefaced with a comment about the misery that is being inflicted on the Iraqi people – on the first day of spring in their, and our, land.

At the office, a friend of mine said that yesterday, Friday, had been a good day because they had had electricity at home and had been able to watch the news on several satellite channels, including the commentaries on Iranian TV which he said had been very good. When I asked him what the response had been among his family, he said the feelings had been mixed: no one had had any love for Saddam, but having gone through so many years of war, they felt sorry for the Iraqi people.

There was another, hidden mix of feelings in the tone of his voice and the look on his face: many of our Afghan friends are not at all happy with what the Americans are doing in Iraq, but they are happy that the Americans have driven the Taliban out of power in Afghanistan.

In the departure lounge, about 15 Afghans – most of them conscripts – and us foreign travellers had Aljazeera’s news to watch. An Al-Jazeera journalist, Amr El-Kahki, formerly with the BBC’s Arabic Service, was reporting from the Iraqi port of Umm Qasr, which the Americans and the British said yesterday they had captured. Amr, who was moving with the US-British forces, said they had taken the northern section of the port. The Americans themselves said they had faced resistance.

An Arab military commentator said the resistance had been unexpected and very significant, and if it continued it would raise the morale of the rest of the Iraqi forces. The commentator, a retired colonel, was very articulate and calm, but clearly a supporter of the Arab cause and openly advised the Iraqi command on how to conduct their public relations to keep international sympathy on their side. It was an extraordinary sight: a television station from a nominally pro-Western Arab state was openly standing against the West – a feeling in line with the protests which were being reported from across the Arab world, and beyond.

As I was watching the news, a Western looking gentleman in his late fifties approached me and asked, in British accent, what the news was all about. I gave him a summary, including the news that two British helicopters had collided over the Persian Gulf, killing their crew of seven.

In conversation later on, we found out that our professions had a lot in common. He is with the British-based, family planning organization, Marie Stopes International, and has set up a family planning and reproductive health advice centre in Kabul. They have worked with other UN agencies, but obviously there is a lot that we can do for them, including putting them in touch with medically qualified Afghan women. Having been to some forty countries on similar missions already, he said Afghanistan was the most challenging, primarily because people were still living with a great deal of uncertainty.

It had been raining heavily in the morning and low clouds were covering the airport by the time I got there. The weather caused a two-hour delay in our plane’s arrival from Islamabad, but we did take off and had a smooth flight to Dubai. This time I’ve been able to take a better view of the Dubai airport. In addition to its size, glamour and sparkle, I was also impressed, as several friends have been, with the staff’s courtesy and efficiency.

Wednesday, 2 April 2003 (London-Dubai-Kabul)

The BA flight to Dubai was about half full. Like other airlines, it had to take a longer route, flying over Egypt and Saudi Arabia, to reach Dubai from the south. But unlike the Royal Brunei that flew straight from Dubai to London ten days ago, BA had a stopover in Larnaca to refuel and change its crew. The planned 45 minute stop-over in fact turned out to be 2.5 hours long because of what the pilot described as a security alert. Something big must have been happening in the war.

The Duty Free area in Dubai was very quiet compared to two months ago when I was there for the first time. There were far fewer passengers around and sales assistants said business had dropped by fifty per cent. Some stalls, like cosmetics and alcoholic drinks, were completely deserted.

On the UN plane, there were some forty of us, including my Filipina colleague, Ermie. Our UNIFEM colleagues, Khalid and Shirzad, came to the airport to collect us. At the guesthouse, I saw Ashraf, Sarwar and Latifa Khanom. At the office everybody was very nice and Khalid invited everyone to lunch. I saw Parvin briefly before she went home to rest. This week she's working part-time.

Wednesday, 2 April 2003 - pm

Today, we enjoyed the bright sunshine and a cleaner Kabul, after several days of rain which have filled up the reservoirs and made it possible to give some areas electricity round the clock. At the office, I was given a new phone and a ‘radio’, i.e. a walkie-talkie, which we are meant to have with us all the time, just in case we need to reach someone in an emergency, and the mobile phone does not work.

Over lunch, our colleagues were talking about the tulips that have grown around Kabul. We might be able to go out on Friday to have a picnic somewhere picturesque, but we will need permission from our security officers. The security situation has been worrying people recently, with fighting continuing in the south, and a number of rocket attacks in other areas. This had been expected to happen, with the assumption that the war against Iraq would make it difficult for the Americans to maintain the same level of military action in Afghanistan.

We had dinner with Parvin and Solmaz and watched a little bit more of the terrible news of the war. Tomorrow, we’re going to have a staff meeting to work out our plans for the next few months. It looks very promising and I am very happy to be here, working on a program which more than anything else depends on our imagination, good faith and determination.

Thursday, 3 April 2003

The day began with the shocking news that the Iranian photo-journalist, Kaveh Golestan, had been killed by a land-mine in Iraqi Kurdistan. He had been there for more than two months. I met his sister, Lili, in London and Oxford and she kept saying that she was worried about Kaveh.

On the way to the office, the bright sunshine and clear sky changed the atmosphere slightly, but it was not to be a warm day – a mix of spring and fall.

At work, things got better. My colleague, Khalid, who had attended a meeting on the BBC’s educational programmes yesterday, gave us a summary of the discussions on health and family issues. These educational radio dramas are aimed at people many of whom have been dislocated from their homes by nearly a quarter century of fighting; who have little access to newspapers or books or other educational materials; and often no proper roads on which to travel. In such circumstances, people lose contact with each other and with the knowledge and experience that would have been handed down from one generation to another.

The scripts for the programmes are discussed by experts from a wide range of UN organisations, including the World Health Organisation, the Food and Agriculture Organisation, UNICEF, UNESCO, and UNIFEM. One of the points that came up during this week’s discussion was that in the past, when Afghanistan had no water purification facilities, people would store spring or river water in clay pots holding a layer of pebbles. Any particles in the water would gradually descend to the bottom of the pot and get trapped under the pebbles, rather than leave it when water was poured out for drinking.

Now that with several years of draught there is little water around, running water is often polluted by the rubbish that is thrown into the streams. In the past, children would be taught that it was a sin to pollute the water. A child who threw anything dirty into the water, it was said, would have had one of his/her eyelashes plucked out as punishment. Nowadays, parents might give a bag of rubbish to a child and ask the child to throw it into the stream.

Another point was about infant mortality and death at childbirth, both of which are very high in Afghanistan, and much of which is simply due to the lack of information or basic medical services. Mothers lose their lives either because no one notices they are ill and need help; or because the husband or his relatives prevent the woman from seeking medical care; or because no medical services are available.

Living as displaced people, maybe in foreign lands, migrating from one place to another, at best crammed into buses or trucks, but very often on foot, individuals, families and generations are torn apart from each other. The very old are either left behind or die because of the severe difficulties of such travels, and the very weak and very young die because basic but vital information and skills that could have saved their lives was stored in the minds of the elderly contact with whom has now been lost because of migration.

It is great that people are enraged when ancient statutes are destroyed, but a great shame that a huge wealth of knowledge about life accumulated over centuries, in other words a people’s living cultural heritage, could disappear without causing an outcry.

Friday, 4 April 2003

This Friday has been great: glorious sunshine; the sight of water in Kabul River that has been dry for more than ten years; brown hills in Kabul turned green; a lively conversation with two Afghan boys while I was walking to the office; a fantastic international photo exhibition; and meeting a friend from my days in Beirut.

This morning was so bright and cheerful that a colleague and I walked to the office. At the end of our road two young boys approached us and, as usual, began speaking English to us. After I replied in Persian, we had a friendly conversation all the way to the office – about 15 minutes away. They said they lived in another part of Kabul but had come to our area to play – I’m sure you cannot guess this one – cricket! Cricket was introduced to Afghanistan by the refugees who returned from Pakistan. But their friends had not turned up and now they were going back to their own neighbourhood to watch a game of football.

They were both from the Shamali region and one of them said he had once been arrested by the Taliban who wanted to know if his father had kept any weapons. Both were smart and articulate. One of them, the 14-year old Abdossamad, answered all my arithmetic questions correctly, and the other one, the 12-year old Fazl-e-Rabbi (My God’s Gift), recited a beautiful poem by heart.

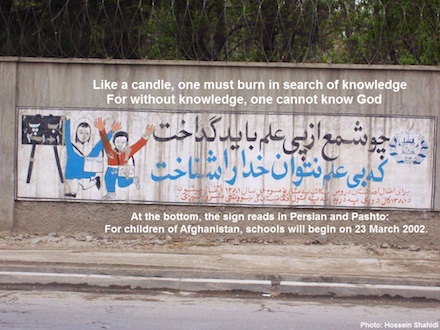

Near our office there’s a sign on a wall, announcing the opening of schools in Afghanistan in March 2002, with line of Persian poetry, the first half of which: ‘Like a candle, one must burn in search of knowledge.’ When we got there, Abdossamad recited aloud the second half of the verse: ‘For without knowledge, one cannot know God.’ This was a rough translation. Here’s the poem in the original, and much more musical, Persian:

Cho sham’ az pay-e elm baayad godaakht

Keh bi elm natwaan khoda raa shenaakht.

By this time, we had reached the office. So I shook hands with the boys, and got their address, hoping that someday I could visit their neighbourhood. They impressed me not only by being smart and articulate, but also because they were so dignified and did not ask for anything, unlike many other little children who sadly beg on the streets. My little friends did point out that many children in Kabul were living in poverty and had to do ‘poor’ jobs, while children with rich fathers had a much better life.

In the afternoon we went to the World Photo Exhibition, the most important international exhibition of photo-journalists’ works, held in Kabul for the first time, organised by the Aina Media and Cultural Center. The exhibition is held in the Afghan Government’s Publishing house which was built more than eighty years ago, but was bombed during the early 1990s faction fights, by which time it had 1,000 women among its employees.

| Recently by Hossein Shahidi | Comments | Date |

|---|---|---|

| Welcome to Herat | 3 | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (38) | - | Oct 13, 2012 |

| Kabul Days (37) | 1 | Oct 05, 2012 |

RECENT COMMENTS

IRANIANS OF THE DAY

| Person | About | Day |

|---|---|---|

| نسرین ستوده: زندانی روز | Dec 04 | |

| Saeed Malekpour: Prisoner of the day | Lawyer says death sentence suspended | Dec 03 |

| Majid Tavakoli: Prisoner of the day | Iterview with mother | Dec 02 |

| احسان نراقی: جامعه شناس و نویسنده ۱۳۰۵-۱۳۹۱ | Dec 02 | |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Prisoner of the day | 46 days on hunger strike | Dec 01 |

| Nasrin Sotoudeh: Graffiti | In Barcelona | Nov 30 |

| گوهر عشقی: مادر ستار بهشتی | Nov 30 | |

| Abdollah Momeni: Prisoner of the day | Activist denied leave and family visits for 1.5 years | Nov 30 |

| محمد کلالی: یکی از حمله کنندگان به سفارت ایران در برلین | Nov 29 | |

| Habibollah Golparipour: Prisoner of the day | Kurdish Activist on Death Row | Nov 28 |