The call to noon prayer beats down from the sun. A laborer mutters his devotion in the scant shade of a sapling.

Guide us along the straight path

The path of those You have favored

Not of those with whom You are angry

Not of those who are lost.

Enough playing and sightseeing at the marketplace. Time to go home for lunch. I had spent the day watching the grape flies at the fruit seller’s shade. They float silently in the fragrant air, their wings blurred around them like halos. They read your mind. Try to grab one and it has already drifted serenely out of the way. No hurry, no panic. They know the future.

On the short walk home, the sun is already bleaching memories of the fruit seller’s paradise. Guide us along the straight path …Why do we need guiding along the straight path? I wonder.

I reach the house, but the gate is locked. I don’t feel like knocking; there is an easier way. The neighbors are building a wall and there are piles of bricks everywhere. After many trips back and forth I have enough bricks to make a step stool with which to climb the wall into the house. My arms are scraped pink by the effort. I sneak to the kitchen and try to startle my mother.

“You better go put those bricks back before the neighbor sees them,” she says.

The next day I pass by the fruit seller’s and go straight to the cobbler’s tiny shop. A pair of my mother’s shoes needs mending. The cobbler flashes a “two” with his fingers and goes back to the shoe at hand. His hair and beard look just like the bristles he uses on the shoes.

“I will wait for them here,” I say as I pull up a stool. He does not hear me. The walls are covered with unfinished shoes waiting to be soled. They look like faces with their mouths wide open.

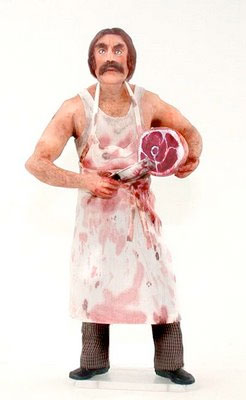

“They are shouting at each other,” I say, pointing to the walls. The cobbler cannot hear them; he is deaf-mute. He emphatically flashes two fingers again. Come back in two hours. So I walk next door to the butcher’s shop to look at the ghastly picture on his window and try to figure out what it means. I hesitate to ask him. Some things are better left alone.

The butcher is a decent man. He has to be, for he is entrusted with doing all our killing. Even though we pass on the act, we are still responsible for the deaths we cause. The killing must be done mercifully and according to the rules of God. The killer must be pure of heart and without malice for the world.

Our butcher was a man of great physical and moral strength. My mother said he reminded her of the legendary champion, Rostam. Rostam was so strong that he asked God to take away some of his strength so that he would not make potholes wherever he walked.

The butcher was very big. Every time he brought down the cleaver, I feared he might split the butcher’s block. His burly hands carried the power of life and death. The carcasses hanging on the hooks and the smell of raw meat testified to this. Above the scales was a larger-than-life picture of the first Shiite imam, Ali, who supervised this Judgment-Day atmosphere with a stem but benevolent presence. Across Ali’s lap lay his undefeated sword, Zulfaghar.

But the true object of my terror was the picture in the shop window. A man was chopping off his own arm with a cleaver. The artwork was eerie, as the man’s face had no expression-he stared blankly at the viewer while the blood ran out. This was the butcher’s logo. Underneath it the most common name for a butcher shop was beautifully calligraphed: Javanmard (man of integrity).

I had asked my mother what the mutilation signified. She had said it was a traditional symbol attesting the butcher’s honesty, but she could not explain further.

“Is the butcher honest?” I asked.

“Yes, he is very honest. We never have to worry about spoiled meat or bad prices.”

“He would rather chop off his arm than be dishonest? Is that what his sign means?”

“Yes.”

“What about other shopkeepers? What have they vowed to do in case they are dishonest?”

“I don’t know.”

“What about the cobbler? Did he do something dishonest? Is that what happened to him?”

“I don’t know.”

“Is that why people kill themselves? Because they have been very dishonest?”

“Look, it is just a picture. It’s not worth having nightmares over. Next time you are there, you can ask him what it means.”

I did not ask him about it until I was forced to by my conscience.

One day my mother sent me out to buy half a kilo of ground meat. She told me to tell the butcher that she wanted it without any fat. She knew it would be more expensive and gave me extra money to cover it. I got to the butcher shop at the busiest time of the day. One good thing about the butcher was that he, unlike other shopkeepers, helped the customers on a first-come, first-served basis. Status had no meaning for him and he could not be bribed. People knew this about him and respected it. When he asked whose turn it was, instead of the usual elbowing and jostling, he got a unanimous answer from the crowd. People do not lie to an honest man.

This gave great meaning to the picture of Ali above the scales. Ali, the Prophet’s son-in law and one-man army, is known for his uncompromising idealism. His guileless methods were interpreted as lack of political wisdom, and he was passed over three times for succession to Mohammad. When he did finally become caliph, he became an easy target for the assassin as he, like the Prophet, refused bodyguards for himself. Shiites regard him as the true successor to Mohammad and disregard the three caliphs that came before him.

When my turn came up, I asked for half a kilo of ground meat with no fat. The butcher sliced off some meat from a carcass and ground it. Then he wrapped it in wax paper and wrapped that in someone’s homework. Sometimes he used newspapers, but because of the Iranian habit of forcing students to copy volumes of text for homework, old notebook paper was as common as newsprint. He gave me the meat and I gave him the money and started to walk out, but he called me back and gave me some change. This was free money; my mother had not expected change. I took the money and immediately spent it on candy.

When I went home, I did not tell her that she had given me too much money. I worried that she would know I had spent the change on sweets and that she would yell at me for it. Around noontime my mother called me into the kitchen. She asked me if I had told the butcher to put no fat in the meat. I said I had told him.

“I thought he was an honest man. He gave you meat with fat and charged you the higher price,” she said sadly.

Now I knew where the extra money came from. In the heat of business he had forgotten about the “no fat” and had given me regular ground meat. But he had not charged me the higher price.

“We will go there now and straighten this out with him,” she said sternly.

I thought about confessing, but I deluded myself into thinking the change had nothing to do with it. After all, he made the mistake. How much change had he given me anyway? Or maybe my mother was wrong about the quality of the meat. I was just a victim of the butcher’s and my mother’s stupidity.

It was still noontime as we set off to straighten out the butcher. The call to prayer was being sung. Across the neighborhood devout supplicants beseeched their maker.

Guide us along the straight path

The path of those You have favored

Not of those with whom You are angry

Not of those who are lost.

I was certainly lost, fighting the delusion like a drug, now dispelling it, now overwhelmed by it. When things were clear, I could see that I had done nothing wrong except fail to get permission to buy candy. The butcher made a mistake, I did not know about it, and I bought unauthorized sugar. All I had to do was tell my mother and no crime would have been committed. The real crime was still a few minutes in the future, when I would endanger the reputation and livelihood of an honest man. I still had time to avert that.

Guide us along the straight path…

When delusion reigned, I felt I had committed a grave, irreversible sin that, paradoxically, others should be blamed for. The straight path was so simple, so forgiving; the other was harsh and muddled. How much more guidance did I need? The prayer did not say “chain us to the straight path.” When we reached the shop, the butcher was cleaning the surfaces in preparation for lunch. He usually gathered with the cobbler and the fruit seller in front of the cobbler’s shop. They spread their lunch cloth and ate a meal of bread and meat soup. In accordance with tradition, passersby were invited to join them, and in accordance with tradition, the invitation was declined with much apology and gratitude.

My mother told him that when she finished frying the meat, there was too much fat left over and she thought the wrong kind of meat had been sold. She asked if he remembered selling me the meat. The butcher was unclear. He remembered having to call me back to give me some change, but he was too busy at the time to remember more. My mother said that no change would have been involved as she had given me the exact change. This confused the butcher and he decided that he did not remember the incident at all. His changing of his recollection added to my mother’s suspicions. Meanwhile, Ali was glowering at me from the top of the scales, his Zulfaghar ready to strike. My face was hot and my fingers felt numb.

Finally, the butcher, who was not one to argue in the absence of evidence, ground the right amount of the right kind of meat, wrapped it in wax paper, wrapped that in someone’s homework, and gave it to my mother. She offered to pay for it, but the butcher refused to accept the money and apologized for making the mistake. When we left, he was taking apart the meat grinder in order to clean it again.

On the way back I felt sleepy. My mother asked if I was all right.

“I’m fine,” I said weakly.

“Your father will be home in a few more days,” she reassured.

“Mother, do you think the butcher was dishonest?” I asked.

“No, I think he really made a mistake.”

“How do you know that?”

“Because he gave us the new meat so willingly. If he were a greedy man, he would not have done that. He probably feels very bad.”

A terrible thought occurred to me. “Bad enough to chop off his own arm?” I asked urgently.

“I don’t think so,” she said.

But I was not convinced. She did not know what awful things could happen off the straight path. “I have to go back,” I said as I started to run.

“Where are you going, you crazy boy?”

“I have to ask him about the picture,” I yelled.

“Ask him later, now is not the time…. ” She gave up. I was already a whorl of dust.

I was panting and swallowing when I saw the butcher. He was having lunch with the cobbler and the fruit seller. What did I want now?

“Please, help yourself,” said the butcher, inviting me to the spread. I just stood for a while.

“Why do you have a picture of the man chopping off his arm?” I finally asked. The cobbler was tapping the fruit seller on the back, asking what was going on. The fruit seller indicated a chopping motion over his own arm and pointed toward the butcher shop. The cobbler smiled and repeated the fruit seller’s motions.

“That is the Javanmard,” the butcher said. “He cheated Ali.”

“Why?” I asked.

“Even when he was caliph, Ali did not believe in servants. One day a man came to the butcher’s shop and bought some meat. The butcher put his thumb on the scale and so gave him less meat. Later he found out that the customer was Ali himself. The butcher was so distraught and ashamed that he got rid of the guilty thumb along with the arm,” he said.

I was greatly relieved. One did not mutilate oneself for committing a wrong against just anybody. It had to be someone of Ali’s stature. Our butcher was safe even if he was to blame himself for the mistake. But I had to be absolutely sure.

“So if one were to cheat someone not as holy as Ali, one would not have to feel so bad?” I asked. Looking back, I see that he interpreted this as a criticism of the moral of the parable. He was transfixed in thought for a long time. The cobbler was tapping the fruit seller again, but the fruit seller could not find the correct gestures; he kept shrugging irritably.

The butcher finally came to life again. “Ali was good at reminding us of the difference between good and bad,” he explained.

I was glad I was not so gifted.

“Would he have killed the butcher with Zulfaghar?” I asked.

“No, in fact I think once he found out what the butcher had done, he went to him and healed the arm completely,” he said, displaying his arms. I looked carefully at his arms, but there was not even a trace of an injury. “A miracle,” he explained.

The fruit seller was able to translate this and the cobbler agreed vigorously. He had something to add to the story, but we could not understand him.

During lunch I told my mother the butcher’s story.

“Now why couldn’t this wait until tomorrow?” she asked, collecting the dishes.

“Mother?”

“Yes?”

“If I were to get some change and not bring it back, what would you do?”

“Did you get change and not bring it back?” She smelled a guilty conscience.

“No, I was just wondering.”

“It depends on what I had sent you to buy,” she said deviously.

“Like meat for instance.”

She pondered this while she did the dishes. When she was done, she donned her chador and asked me to put on my shoes.

“Where are we going?” I wondered.

“To the butcher’s,” she said curtly. “You are going to apologize and give him the money we owe him.”

“It was his mistake,” I protested guiltily.

“And you stood there all that time, under Ali’s eyes, and watched him grind us the new meat without saying anything.”

I followed her dolorously out the gate. I could tell she was upset because she was walking fast and did not care if her chador blew around. But halfway there she changed her mind and with a swish of her chador ordered me to follow her back home.

“Why are we going back, Mother?”

“If this gets out, they will never trust you at the marketplace again,” she said angrily.

“So we are not going to apologize?”

“Of course you will apologize. You are going to give him your summer homework so he can wrap his meat in it.”

The summer homework filled two whole notebooks. The school had made us copy the entire second grade text. Completing it had been a torturous task and a major accomplishment. My mother had patiently encouraged me to get it out of the way early in the vacation so that it would not loom over me all summer.

“What will I tell the teacher?” I begged.

“You will either do the homework again or face whatever you get for not having it. Or maybe instead of the homework you can show her the composition you are going to write.”

“We did not have to write any compositions,” I whined.

“You are going to write one explaining why you don’t have your homework.”

So, for the fourth time that day I went to the butcher shop. It was still quiet at the marketplace; the butcher was taking a nap. He woke up to my shuffling and chuckled groggily when he saw me.

“I was looking for you in the skies but I find you on earth (long time no see),” he said.

I gave him my notebooks and told him that my mother said he could wrap meat in them. He thanked my mother and apologized again for the mistake. My mother had told me not to discuss that with him, so I left quickly.

Within a few days, scraps of my homework, wrapped around chunks of lamb, found their way into kitchens across the neighborhood.

I opted for writing the composition explaining the publication of my homework. My mother signed it. The teacher accepted it enthusiastically, and while other students were writing, “How I spent my summer vacation,” I was permitted to memorize the opening verses of the Koran. I had heard it many times before and knew the meaning, but I did not have it memorized. It goes:

Guide us along the straight path

The path of those You have favored…

A few summers later, the butcher became involved in the uprising against the Shah. He tacked a small picture of Khomeini next to Ali and Zulfaghar and would not take it down. His customers, including my mother, urged him not to be so foolish.

“Was Ali foolish to refuse bodyguards?” he asked.

“You are not Ali, you are just a butcher. Khomeini is gone, exiled. At least hide his picture behind Ali’s picture.”

When he disappeared, we all worried that he would never come back. But a few days later, he opened his shop again and, as far as I know, never hid anything anywhere.

***********

Khomeini lost his first battle with the Shah, but he came back fifteen years later to destroy the monarchy. He was perceived by most Iranians to be a man of unrelenting integrity, much like how I remember the butcher. It was easy to believe that under Khomeini’s leadership Iran would be cleansed of its corruptions. The greedy and the dishonest would no longer have the advantage over hardworking citizens grateful to God for their daily bread. Khomeini’s refusal to compromise with what he thought to be evil eliminated the riddles of our conscience. The line between Good and Evil became as sharp as the slice of a sword. And so the blade promised to establish the laws of Heaven on the land. How many incarnations of Hell have been conjured by those that would live in Heaven?

(From The Mullah With No Legs and Other Stories, by Ari Siletz)