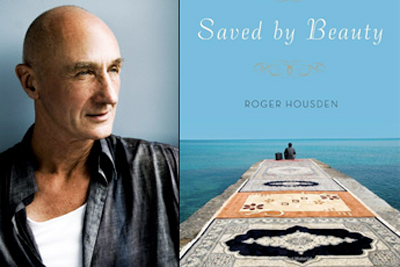

A lyrical panorama of contemporary Persian politics and culture, “Saved by Beauty” by Roger Housden gives contour and nuance to our idea of Iran, and introduces us to complex, very memorable characters-from the artists who refuse to live elsewhere, despite governmental limitations, to the poetry-quoting intelligence agents who threaten the author with prison. See video.

EXCERPT

In Isfahan, Iran, blue against a blue sky, is the most beautiful building I have ever seen. Entering the Lotfollah Mosque, I made my way to a corner and sat on the floor beneath the soaring dome to take it all in. Then I lay down and gazed up. A melody of light played through the latticed arches. At the dome’s center was an explosion of yellow, a sunburst from which a bewildering forest of tendrils and blossoms laced their way over the dome’s surface. I began to see shapes within shapes, and to feel that I was being showered not only with beauty but with wisdom; for the intelligence inherent in the design and proportion was as tangible as the effect of the rain of color.

Its beauty humbled me, shattered my mind with its color and light, undid the threads of my thinking with its spiraling turquoise columns, like twisted ropes, and running Arabic script all in white against the deepest of lapis blue. Unlike any exercise in prettiness or mere display, beauty of this order is at the same time devastating and our salvation. Devastating in the sense of emptying us of self, of thought, of ordinary feeling, and our general notion of identity; salvation in that this emptying opens the way for the divine presence, the incursion, the down pouring of grace. This continual emptying and filling is at the heart of Islam, whose meaning is “surrender.”

For several moments even the guard disappeared and I was alone. The building seemed to breathe in the silence. Finally a little girl with bangs and a sort of basin haircut and huge black eyes ran into the sanctuary ahead of her mother and, seeing me, immediately flitted over and shot out her hand. I took it in mine, and we broke into broad smiles.

The girl ran off to her mother, and I stood up and walked slowly over to the mihrab, the niche that points to Mecca. Again, spiraling around the mihrab was a dizziness of vines in yellow on blue, and immediately above the niche was a latticed arch whose pattern was two winding vines embracing and weaving in and out of each other like lovers — which is exactly what they were, the union of lover with beloved, the same motif that ran through all of Persian mystical poetry. Finally, there in the very center of the mihrab, I noticed the turquoise shape of a dervish begging bowl.

We are beggars, all of us, before the mystery. I took my time and wandered eventually out of the sanctuary, back into the dim entrance passage and out into the full light of day.

I stopped for a moment at the entrance portal again. Looking back up at the honeycombed marvel of stone work above the door, I felt a wave of gratitude for the Lotfollah Mosque. It had clarified me, and revived my pride in the human race.

An old man with a cane was sitting stooped on the ledge by the door. He beckoned me toward him with a smile. I sat down by him and he said, with a toothless grin,

“Are you happy with your life?”

“I am,” I said, both surprised and delighted by the simple intimacy of the question; aware even as I answered of conditions that I would perhaps like to be different, but that did not at root impinge on the happiness I felt — especially in that moment, having emerged from the most radiantly beautiful building I had ever set foot in.

“Thank you,” he said, with a broad grin. “Thank you!” I am happy with my life too.

“My son lives in Michigan.”

The word Michigan dissolved in the wind. Both of us sat there in the sun, looking out in silence over the square beyond. Dostoevsky’s words floated through my mind: “Mankind will be saved by beauty.”