PARTS: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30, 31, 32, 33, 34, 35, 36, 37, 38

The Paradise of Childhood

Thursday, 15 May 2003

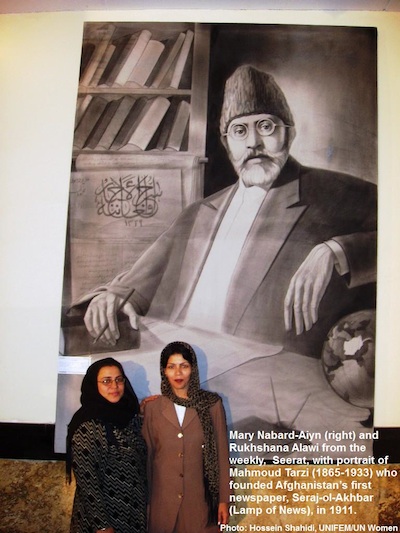

Trust is very hard to gain, but easy to lose, and we finally seem to have won the confidence of our television friends, including the one who said last week that I had wasted an-hour-and-a-half of his time. But before I tell you about that, a brief account of an impressive journalist, Mary Nabard-Ain, who produced Afghanistan’s first women’s newspaper very soon after the fall of the Taliban. The weekly, Seerat (or Character), first appeared on one sheet of paper, but now comes out in four pages with pictures, and an English language section which is very popular among students.

The paper is printed in 1,000 copies and sells for 1 Afghani, less than 1p, a copy. It is funded by UNESCO, but needs more money now because Mary wants to increase the print run to 2,000 to meet the rising demand in the provinces, where people take turns to read the paper. All she needs for this is about $6,000. We don’t have the money, but I am trying all potential sources of funding for her, and will be helping her raise funds by running appeals in the paper, something that had not crossed her mind.

After the meeting with Mary, we went to the TV station and all four of our friends were there. I told them how excited I had become by the Azizi School; how grateful I was for the opportunity they had given me to go there with them; and how important it was for the achievements of the staff to be promoted, rather than just their difficulties. I also said that I was doing my best to bring the school to the attention of the Afghan authorities and the world so they could get support.

As for the television team, I said we were doing our best to get them a car, although we could not make any promises, and that I would be delighted to go to their office for up to two hours every day to make sure they would plan their work more effectively. I also said the production team, which really means the one male director, would benefit from discussions with women, especially women journalists who were producing twenty magazines in Kabul. As a bonus, I said we at UNIFEM would give them a collection of all the magazines so they could develop their own library.

When I had finished, the director said he really did not need anyone else to come in and he was OK with the way things were, except that the station had its own policies imposed by the government, which meant they could not play some types of music – which means women’s voices – and make exciting programmes. At this point, the head of department cut in and said to his colleagues that I did not mean to change government policy, only to help them do a better job within the same framework.

He further reassured the director by saying that all I would have to do would be to drop in on them an hour or so every couple of days to make sure they were alright. He also welcomed the idea of using women journalists and their magazines as a source of advice and information, as well as a subject of reports about how the journalists were doing their job.

For the first time in our meetings, there was a lot of genuine warmth in the head of department’s voice and I felt he had really believed that we were there to help. I think as an Afghan man he also felt proud of what Afghan women had done, as reported by a non-Afghan man. His approval meant that his staff were also much more receptive and there was a burst of enthusiasm about how the programme could be improved.

There was then another source of engagement at the TV station, our sixth workshop on running panel discussions, with four senior members of staff. We turned our own group into a panel, each of us taking turn as the host, questioning the others about the importance of incorporating women’s rights in Afghanistan’s new constitution.

This workshop has not been very smooth to organise either. We started with six participants, two of them women, one of whom soon fell ill and never came back. On the third session, there were only three people, two of whom came between 1:30 and 1:45 – for a workshop that was meant to run from 1 to 3. I did complain and said there was no point in continuing if they could not be bothered to come in, or be on time.

Things improved for the fourth and fifth sessions and today we had a great time, with a lively discussion of women’s rights and interviewing techniques. At the end of the session I asked the journalists if they wanted us to continue, and they said they did. So we’re going to go on for another three sessions, each time with one aspect of women’s rights as the focus of our practice panel discussions.

At the very end of the day, Hashem Jan told me that he had delivered a supply of turf to the guest house and he would be coming in tomorrow, Friday, at 9am to fix the lawn and tidy up the rest of the garden. Hashem Jan is himself now excited about our gardens and has been telling me, with a glint in his eyes, that he plans to make another flower bed on the right hand side of the garden where there are a few wild bushes with some construction rubbish hidden behind them. I think all we need to do is let Hashem Jan do what he thinks is best, and I am sure it will be the best.

Saturday-Sunday, 17-25 May 2003, Kabul-Dubai-London-Kabul

Six weeks ago, on March 22, as I was passing through Kabul airport, Al-Jazeera television was showing the first stages of the American-British attacks on Iraq, with 1,000 missiles fired on Baghdad overnight. Everybody was gazing at the screen, even if they knew no Arabic.

This time round, Iranian television was on, showing children’s programmes which were in fact quite well produced. But few people were watching, even from among those who know Persian. For news, the set was switched over to Al-Jazeera, again with very few viewers.

Out in the sunshine, a huge, black American military transport plane was taxiing down the Kabul airport runway. Further along, the German flag was flying on top of the control tower. Still further down, on top of another airport building, the flags of several western countries, whose soldiers make up the security force in Kabul, ISAF.

In the four months I’ve been here, the airport has improved considerably. For a start, you can now find a trolley to take your luggage inside, rather than be surrounded by large numbers of people who want to carry your luggage for you. There is a refreshment stall just outside the departure lounge – a much welcome addition, especially since flights can get delayed for several hours.

Dubai airport was calm and quiet both last week when I flew in from Kabul, and during my flight back to Kabul. In contrast with the Al-Jazeera reports in March of the killing of the Iraqis by their ‘liberators’, the duty free area was now filled with loud, happy music. One Arabic newspaper carried a story which said Saddam Hussein’s two daughters were seeking asylum in several countries, including Britain. Another paper was wondering if Saddam had been deceived by his son Qusai.

The cover of Time magazine was filled with dozens of tiny pictures of Ben Laden – still at large, nearly two years after 9/11. It reminded me of the CNN reporter, David Ensor, who was sceptical about the Americans’ chances of finding Saddam, considering he has several doubles. The American forces, he said, had still not been able to find two much more conspicuous men: ‘a six-foot Arab and a one-eyed Afghan’.

[Bin Laden was killed in a US attack in Pakistan eight years later, 2 May 2011. However, his death not only did not signal the end of the catastrophe in Afghanistan, but the attack was criticized for its violation of Pakistan’s sovereignty and the killing of an unarmed person by heavily armed US troops, which further undermined the notions of international justice and rule of law.]

Instead of threats of war or terrorism, signs at the Dubai airport warn against SARS. The warnings are specifically addressed to passengers who may have visited China, Hong Kong, Singapore, Vietnam, or Toronto. A couple of weeks ago, a commentator on Iranian television was suggesting that the American-British controlled global media overplayed SARS to put pressure on China, which had opposed their attack on Iraq.

Dubai airport has a very impressive building and pretty efficient staff, except, it seems, when it comes to passengers flying to Afghanistan. We have to use the less glamorous of the two terminal buildings, along with passengers flying to Iran on one of the smaller Iranian airlines. We have to check in at the fancy terminal 1, and then take a bus to terminal 2.

The check-in area, which could be used by around seventy people at a time, is a cramped corridor, with about half a dozen seats and no toilets or any other facilities. Anyone needing anything will have to go back into the duty free area – a trip which requires two more rounds of having your hand luggage x-rayed. So most people don’t bother. It took each one of us about an hour’s queuing to have our tickets examined, something that in another part of the airport would take 10 minutes.

Still, we managed to check in and get on our flights: the Afghan passengers and a few foreigners boarded the Afghan airline, Ariana’s Boeing, and we, about seventy ‘internationals’, got on board the UN’s Fokker jet, which took off an hour later than Ariana. About an hour from Kabul we were told by the pilot that the weather there would not allow us to land. Instead, we had to go to Islamabad, from where we flew to Kabul after a two-hour wait.

This was a good opportunity to see some of Pakistan’s landscape, many parts of it fertile and green, like much of the rest of the Indian sub-continent. One’s thoughts inevitably turned to the partition of India, and before that to the Durand Line, drawn in 1893 by the British to separate India from Afghanistan. The Durand line partitioned the lands inhabited by the Pashtun people, leaving some of them in Afghanistan and the rest in what was to become Pakistan some sixty years later. The two partitions have been major contributors to a century of strife and suffering by the peoples inhabiting this part of the world. [Although shown on most maps as the western international border of Pakistan, the Durand Line is not recognized by Afghanistan. For the text of the Durand Line Agreement, signed on 12 November 1893, between the ruler of Afghanistan, Amir Abdur Rahman Khan, and the Foreign Secretary of British India, Sir Henry Mortimer Durand, see here.]

The biggest news of the week I’d been away was the killing of three Afghan soldiers by the American soldiers guarding the US embassy. The Afghan soldiers had been moving weapons in their garrison which is opposite the embassy and the Americans had thought something nasty was about to happen. It did, but not as they had feared. The incident has been described as a misunderstanding. But this did not stop a demonstration on Saturday by several hundred people who threw mud at the American embassy and shouted ‘Death to America’, ‘Death to Bush’, and ‘Death to Karzai’.

Back at the guest-house, it was a delight to see the result of Hashem Jan’s work in our garden: blossoms in all colours, and a lawn which looks more respectable by the day.

Monday, 26 May 2003

An exhibition of Iranian goods is starting in Kabul tomorrow. This morning we had time to go and visit the site as it was being prepared. The exhibition – with a range of goods from biscuits and fruit juices to cars and road-diggers – takes up the entire space that last year was dedicated to Afghanistan’s Loya Jirga, which endorsed the current administration, and this year saw the International Women’s Day celebrations.

Not only have the one big and two small ‘tents’ been filled, but a lot of open space has also been taken up by stands which were being set up this morning. The work was being done mostly by men, but there were also a few Iranian women, including two who were moving massive truck tyres around in one stall and another who was overseeing another heavy industry booth.

I’d gone there with two female Afghan colleagues, both of whom were impressed with what they saw and one of whom was full of praise for the quality of Iranian goods. I said that twenty years of American sanctions had in fact helped promote Iran’s domestic industry and the need to reach the international markets had imposed the discipline of quality control on the producers.

The show in Kabul is a repeat of one held in Mashhad a while ago, pictures of which were shown in an Afghan TV commercial about the exhibition. Judging by the structures that were being put together, the exhibition appeared to be well designed and the one in the TV commercial looked well stocked and properly lit. I met one of the designers of the show while he was busy putting up banners on the perimeter fence – a young man based in Mashhad, with a flashy business card and his own website.

One of the signs had the name ‘Green House’ on it, along with the logo of a green leaf, the same as was painted on the wall of a house in our neighbourhood. The Iranian designer told me that the name belonged to a firm working with the Iranian embassy to promote trade and travel between Iran and Afghanistan. This explains why the building that used to be called ‘The Green House of Khorassan’ has now lost the last word of its name: almost certainly an effort to avoid arousing suspicions that Iranians want to regain parts of Afghanistan that were called Khorassan only a hundred years ago.

The suspicion is in fact reinforced by comments such as what we heard from another Iranian man while visiting the stalls that were being built. Having told my colleagues that they looked Iranian, the Iranian gentleman then went on to say the Afghans used to be Iranians in the past, anyway. Such Iranians do not seem to know that Sultan Mahmoud, one of the most powerful kings of Iran, was from the city of Ghazni, in what is now Afghanistan.

So, one could say that Iranians too used to be Afghans in the past. Except that Mahmoud was of Turkic origin while strictly speaking, Afghans are really only the Pashtuns who originally lived in the mountainous area that is now the south and east of Afghanistan, and north and west of Pakistan. The Pashtuns were only briefly ruled by the government of Iran, under Nader Shah Afshar, 1736-1747, who was a Turkman, rather than a descendant of Cyrus or Darius.

After the exhibition we went to the Ministry of Higher Education in West Kabul where my colleagues needed to get certification for their university education, interrupted by the war and migration to Pakistan, which they now wish to complete. What to them was a simple task of getting a signature on a document that should not have taken more than 10 minutes, turned out to be a journey of more than an hour through a whole series of offices in the Ministry, collecting one signature at every step along the way.

They were finally told that the Ministry had no trace of their documents, which may have been transferred to Pakistan, where they were studying, before being sent back to Afghanistan, not to Kabul, but to a city in the south-east of Afghanistan, on the border with Pakistan. They now have to travel to that city, hoping that their papers will be found and brought back to Kabul for another signature collecting excursion before they can continue their search for knowledge. My colleagues explained that the staff at the Ministry were all working hard and were helpful, but this was the system in which they had to operate. I have seen similar scenes myself and believe that they are right.

While my colleagues were charting the corridors of the Ministry of Higher Education, my friend Ehsan, one of our drivers and a great fount of knowledge, took me for another tour of West Kabul. I had already seen some of the destruction there, caused by the years of factional fighting among the Mojahedin after they overthrew the PDPA government. But I believe I still have not gotten to the bottom of it: exactly how and why it all happened.

One new piece of detail I saw today was a huge tract of land, completely bare except for a few broken walls scattered around it. Ehsan explained that in the past, the wasteland had been covered in mulberry trees and the walls used to surround a silk making factory. People used to come to the area to pick and eat the mulberries, and silkworms would feed on the mulberry leaves.

On the other side of the road are the ruins of a whole range of buildings which used to belong to the Ministry of Defence. Right in front of you, there’s the gutted shell of a former Royal Palace still referred to as Dar-ol-Aman, the Sanctuary. Further up the road to the right, you will find the remains of the Kabul Museum, itself turned into an object of historical significance. The museum’s stock was looted years ago, just like what happened in Baghdad recently.

And of course you’ve all heard of Kabul Zoo, which is more or less in the same area I visited today. During the fighting, most of the animals died or were killed, and the zoo’s lion was reported to have been blinded by a grenade thrown at him by the Taliban. You’d be relieved to know that the poor thing has now died.

An Australian colleague of mine who went to the zoo with her husband a few days ago could not stay there for more than a few minutes. The couple had to leave after being surrounded by Afghan visitors who had found them much more interesting to watch than anything remaining in the cages.

A few weeks ago, I told you of a school with nearly 6,000 students and hardly a glass pane on a window or a door to a room. Today I saw another school with probably the same number of students and an equally amazing architecture. This is a girls’ secondary school based in a multi-storey building that used to be Kabul University’s hall of residence and was inaugurated very shortly before the PDPA government’s fall in 1992.

Made of concrete and iron, the building did not collapse under the shelling and machine gun and rocket fire of the following years, but lost all of its exterior walls. Now, passing by the school, you can see the students in classrooms which look like rooms in a dolls’ house – without a single wall blocking the view. It’s a miracle that the girls don’t fall down – or don’t they?

We also drove by Lycee Habibia, one of Kabul’s former elite high-schools for boys, where English was taught as the foreign language. The school still lacks windows; its walls are pockmarked by shell- and bullet- holes; and there are black patches here and there where the building had caught fire. Another elite school, Lycee Istiqlal [Independence] that was French-sponsored and taught the French language has now been rebuilt to a very high-standard.

We were passing by Lycee Habibia at around noon and the entire pavements and part of the main street were filled by hundreds of cheerful students going home. Later on, I spoke with Ehsan of the happiness in the Afghan children’s eyes and how they become depressed as youngsters, without a clear future ahead of them. Ehsan responded by gently reciting one of the many lines of poetry he knows by heart:

Tefli-ye damaan-e maadar khod beheshti boodeh ast

Taa beh paa-ye khod ravaan gashtim, sargardaan shodim.

A paradise it was to be in one’s mother’s lap as a child

Walking on our own feet, we have been wandering in the wild.

***